Franca Mancinelli (b. 1981) is one of the leading poets of her generation and has received several important prizes in Italy. I have had the pleasure of translating all of her published poetry to date: her prose poems in The Little Book of Passage (The Bitter Oleander Press, 2018) and her verse poetry in At an Hour’s Sleep from Here (The Bitter Oleander Press, 2019). Her writing is cherished by readers because of the way she grapples with wounds, losses, and what she has called “fault lines”—sometimes personal in origin, sometimes not. By writing, she often seeks to transform these negative events or situations into something potentially affirmative. The title of her new book of poems, Tutti gli occhi che ho aperto, which is forthcoming in September at Marcos y Marcos, comes from a line in one of her poems that expresses this new possibility of vision: “All the eyes that I have opened are branches I have lost.”

Over the years, Mancinelli has also written compelling personal essays. Published in anthologies and journals, these texts often evoke her hometown of Fano or meditate on works of art. Such is the case with “Living in the Ideal City: Fragments in the Form of Vision.” Mancinelli bases her text on a fifteenth-century Italian painting that is found in Urbino at the National Gallery. The painting represents an “ideal city” from which all, or nearly all, the inhabitants seem to have fled, arguably because of some invasion or plague-like disaster. Her text is a kind of reverie on this painting: its architecture, its empty city square and buildings. It raises the question of stepping into the painting, of having “the courage to cross the threshold, [to] enter the darkness, hollow and round like a belly that has taken you back into itself.”

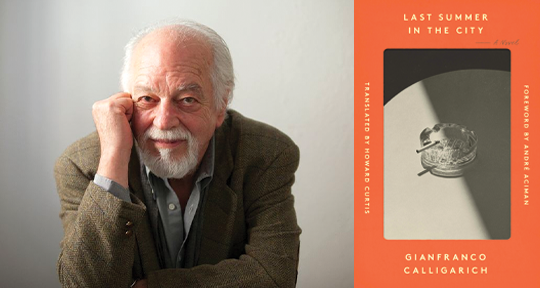

—John Taylor

It emerges when I close my eyes. As clearly as an island suddenly appearing beyond the haze and the mist on the horizon. You see it and can only believe your eyes even if you know you are daydreaming. It happens every time in a different light, as if that square and those streets were the setting of a story. Perhaps only the ghost of a voice that has taken a breath, a gust skimming over the cobblestones, whirlwinding dust across the space, beating lightly on the windows like a bird that has lost its flock.

With sure footsteps, I was heading towards the half-open door. That of the large pagoda a magic spell had brought to a stop at the center of this gently drawn desert. I was moving forward over the large, ash- and sand-colored marble slabs. I could not take my eyes off the geometry seemingly guiding me to the center, like a rolling marble that gathers speed, approaching the hole where it must fall. The darkness beyond the door and a growing fear could have gripped my body and kept me from moving, but it was impossible: my steps continued towards the center while my terror was blooming like a black flower. The door might have opened slowly, then widely, to the breath of the void barely covered by the constructions that now seemed made of cards. They have been aligned in a lukewarm light, but, as you see, they cannot halt the fathomless blackness pressing outwards from the windows and the half-open doors. If you enter the pagoda you sink into the center of the universe, in an endless fall. The beast looks at you, awaits you, pretending to sleep with its hollow eyes: six large square pupils in a clear mellow sky that tells you not to believe in the darkness, not to be afraid. Come to the center; enter. You can imitate a childhood game and jump only on the light or the dark slabs. Precisely, calibrating each movement as if your life depended on it. With such concentration, obediently, you can advance to the foot of the staircase. Now you’re there, standing in front of the dark crack. You have gathered all the soft light of this scene; you have the balmy sun concealed by buildings but warm and sure, as in a late morning without school. You can see the pagoda slowly turning on its axis like a carousel without horses and without music, so slowly that it seems almost motionless; yet it rotates—of this you are sure—rotates like the earth. At the top, the almost invisible thread supporting it could lift it up again, restoring its airy foundations. READ MORE…