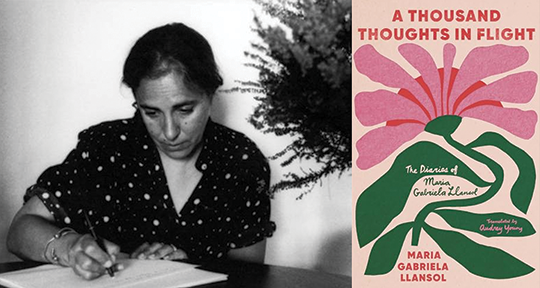

A Thousand Thoughts in Flight by Maria Gabriela Llansol, translated from the Portuguese by Audrey Young, Deep Vellum, 2024

A Thousand Thoughts in Flight, the diaries of Portuguese writer Maria Gabriela Llansol, is divided into three sections: “Finita”, “A Falcon in My Wrist”, and “Inquiry into the Four Confidences”. Comprised of three books from the seventies that Llansol left behind when she passed away in 2008, these volumes were the only ones to be published in Portuguese during the writer’s life, and are also the first of her non-fiction writings to appear in English, thanks to the work of translator Audrey Young. In his introduction, the critic João Barrento describes these private texts as “osmotic diaries: their genesis, their development, and their final form are inseparable from Llansol’s other books, which always accompany them and are interwoven with them”. This is true not only in the conceptual but also the literal sense; the first diary begins the day she finishes The Book of Communities—the first volume in her acclaimed trilogy Geography of Rebels—and ends the day she finishes The Remaining Life, the second volume, in 1977. The second diary picks up when she is finishing In the House of July and August, the final volume, and beginning to write her second trilogy, while also providing glimpses at the author brainstorming her duology, Lisbonleipzig.

Llansol is a generous and poetic writer, sensual in her descriptions and intensely attuned to the metaphysical and the otherworldly, coalescing history, philosophy, and physical experience; these qualities are boldly apparent in her fiction, but appear with an experimental and kinetic mode in these diaries. A common thread across the volumes is silence: everything that remains in the journal is a “draft”, consisting of left-out pieces and vacant spaces for contemplation, and this attention and appreciation reserved for emptiness becomes integral to the diaries’ form. Silence manifests in the common use of gaps in the text, indicated in certain places by a horizontal line (________), and more compellingly in other places as unannounced fragments of poetry. And in between these fragments is life. She moves all around Belgium, from Louvain to Jodoigne and finally to Herbais, where she and her husband Augusto Joaquim run an experimental school as part of a cooperative—which also makes and sells furniture and food. There, Llansol cultivates her own garden, which provides a bouquet of scenes and observations for her diaries, and immerses herself in music. Still, she never pauses in her pursuit of literature, of writing and reading about theology, philosophy, the lives of poets and mystics. It is only in the final diary that she moves back to Portugal’s Sintra, sometime in 1983, remaining there until her death. READ MORE…