I stand in my basement facing stacks of cardboard boxes, the remnants of my last cross-country move out to Boulder, CO. If you were to take a cross-section of each box, you would see the sediments of everyday objects: a top layer of clothes; the occasional sweater enveloping a ceramic mug; a layer of miscellaneous household necessities (clothes hangers, desk supplies, etc.); and finally, a thick deposit of books.

At the bottom of one of these boxes I found a thin book, barely visible between the thick spines of a heavily annotated copy of Bolaño’s The Savage Detectives and a fat collection of Pushkin short stories. I pulled out the paperback, which turned out to be a Brazilian novel, The Brothers, written by Milton Hatoum and translated into English by John Gledson. I couldn’t be sure if I had actually read the book before rediscovering it in the crevice of a cardboard box.

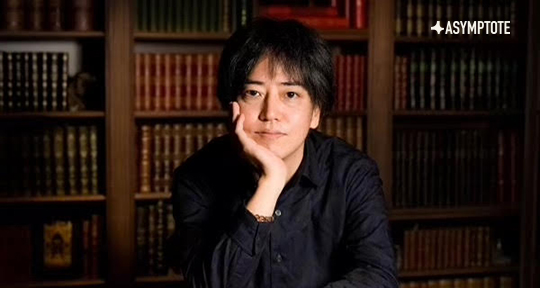

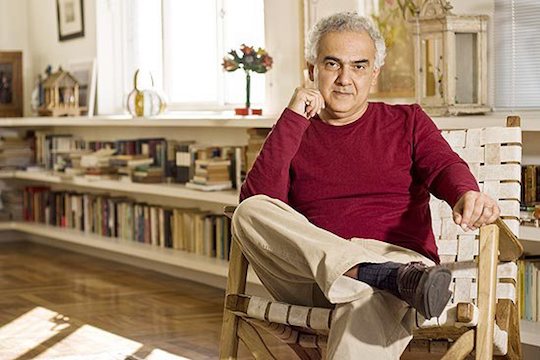

I flipped to the copyright information. The original was published in 2000, with the English translation released two years later. Milton Hatoum is a Brazilian author of Lebanese descent, born in 1952 in Manaus, a city in the Amazon. I flipped to the blurb, which promised the story of a Lebanese immigrant family, focusing on the rivalry between two twins, Yaqub and Omar, who live in Manaus in the latter half of the 20th century.

It’s an intriguing premise, one that draws on the age-old trope of brotherly rivalry, harkening back to Cain and Abel, to The Brothers Karamazov, and to Machado de Assis’s Esaú e Jacó. The novel promised to capture the author’s own experience as a man of Middle Eastern descent from a peripheral region of Brazil. I couldn’t remember how it went from my bookshelf to being snugly packed, which made me curious to investigate further. I left my final box unopened, sat down on the pillows and blankets I had piled on the floor, and began reading. The novel opens with an epigraph, a quote from a Carlos Drummond de Andrade poem:

“The house was sold with all its memories

all its furniture all its nightmares

all the sins committed, or just about to be;

the house was sold with the sound of its doors banging

with its windy corridors its view of the world

its imponderables.”

The narrative then begins with Yaqub’s homecoming to Manaus from Lebanon, where he had spent some years of his youth, and the reuniting of the two twins under a single roof. Hatoum unveils ever-mounting tensions amongst members of the family through their domestic alliances and conflicts, and the touching and torrid backstories that define those relationships; rich descriptions of setting provide a fascinating portrait of Manaus, albeit one that is devoid of exoticization; and the complex exploration of character in simple, quotidian situations calls upon the wide-ranging tradition of the family saga in literature.

READ MORE…