Translators Ian Haight and T’aeyong Hŏ have forged a remarkable partnership in bringing the timeless beauty of classical Korean poetry to English readers. Their work spans centuries, breathing new life into poetic masterpieces originally composed in hanmun, or ‘literary Sinitic’, the written language of Korea’s past. Together, they have delivered evocative English renditions of Borderland Roads (2009) by Hŏ Kyun and Magnolia and Lotus (2013) by Hyesim—both of which were catalogued in The Routledge Companion to Korean Literature (2022). Their more recent projects include Ch’oŭi’s meditative An Homage to Green Tea (2024) and the eagerly anticipated Spring Mountain (forthcoming June 2025) by the poet Nansŏrhŏn, all from White Pine Press, a New York-based publisher.

Through their Korean Voices series, White Pine Press has long been a bridge between Korean literary tradition and global readership, featuring works by writers Park Bum-shin, Ra Heeduk, Park Wan-suh, Shim Bo-seon, Eun Heekyung, and translators Hyun-Jae Yee Sallee, Suh Ji-Moon, Kyoung-Lee Park, and Amber Kim, further cementing its role as a vital conduit for transcultural dialogue.

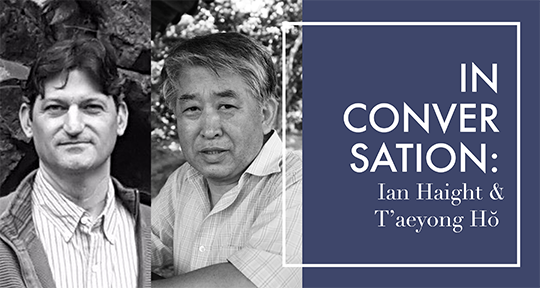

In this interview, I spoke with both Ian, based in Ramstein, Germany, and T’aeyong, in Pusan, Korea, on translating poetry originally written in hanmun, as well as the historical and contemporary divides between what’s revered as cosmopolitan and what’s relegated as vernacular—in language and broader cultural contexts.

Alton Melvar M Dapanas (AMMD): For readers who can read Korean literature only through translation, could you briefly explain what hanmun is? Why did Korean poets, before the invention of the Korean script (kungmun or chosŏnmun) in the mid-fifteenth century, write in this orthography? Additionally, how distinct are classical and contemporary language, ‘literary’ and ‘vernacular’ language, and written and spoken language in the modern Korean literary landscape?

Ian Haight (IH): Hanmun is the Korean use of classical Chinese to write literature. Kungmun is an older term for what we now call hangul in South Korea, which is the contemporary written language of South Korea. Chosŏnmun is pretty much the same thing as hangul, but it is for North Korea. There are some regional dialectical differences between chosŏnmun and hangul, and owing to the political ideologies of North and South Korea, there are also some differences in the words and how some words are written.