In this month’s of newly released translations, we are featuring works that traverse across landscapes of psychology, politics, perspectives, and coastal enclaves. From a travelogue that corporealizes a vision into reality, a fragmented ghost story that equally interrogates readership with writership, and a psychically dense political fiction that follows the twists of truths into fictions, these works are full of metamorphoses, imaginations, and materializations—all that possible within the realm of the text.

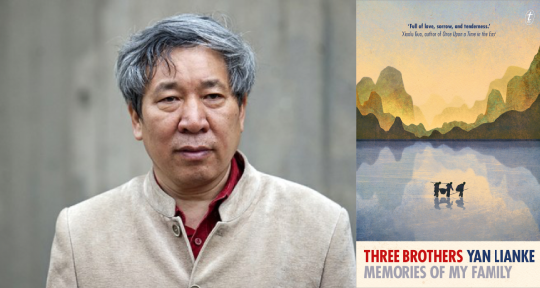

A Line in the World, A Year on the North Sea Coast by Dorthe Nors, translated from the Danish by Caroline Waight, Graywolf Press, 2022

Review by Samantha Siefert, Marketing Manager

A line extends from Skagen, Denmark to Den Helder, Holland—a complex, jagged, six hundred mile stretch of coast. On a map, it is a fixed mark, something definite and present, representing a real place that exists today: the division between land and sea, a place of dunes and marshes, sweeping tides, surging storms, wind farms, gulls, and people. In A Line in the World, A Year on the North Sea Coast, celebrated Danish author Dorthe Nors asserts her dream for this line to be less static and more flexible, persistently animated, always moving, ever changing, evolving with its points marked in time just as much in time as they are in space. Her line reverberates heritage and memory, holidays, tragedy, Vikings, shipwrecks, disco ferries, and local gossip. In this first work of nonfiction, Nors brings Denmark’s western coast to life in fourteen essays, now available in a beautiful translation by Caroline Waight.

Each essay offers an exquisite, layered exploration of a different stretch of that wild North Sea coast, and the first one begins at the top. Nors is from west Jutland, but she has found herself living in Copenhagen, with a noisy neighbor next door and a hash dealer below, and she comforts herself there with sounds of the sea played through an app on her phone. She did not plan to write a book of essays (she was supposed to be working on a novel), but her publisher was insistent. They asked, and then they asked again.

I said, ‘I’ll have to think it over,’ and I did. Or I dreamt. In the dream, I was setting off across the landscape in my little Toyota. I saw myself escaping several years of pressure from the media by driving up and down the coast. Me, my notebook and my love of the wild and desolate. I wanted to do the opposite of what was expected of me. It’s a recurring pattern in my life. An instinct.