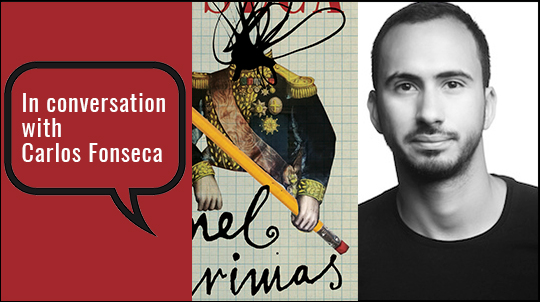

Carlos Fonseca is the author of Colonel Lágrimas, first published in Spanish in 2015 by Anagrama (Barcelona) and coming out in English on 4 October from Restless Books. A British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Cambridge, Fonseca’s research interests lie in Latin American literature, philosophy, and art history, and the formal links between novels and politics, among many others. He was born in Costa Rica and grew up in Puerto Rico, but he considers himself Latin American.

Blog Editor Hanna Heiskanen interviewed Carlos over email about his debut novel, the people who inspired his characters, and his thoughts on identity and the evolving nature of memory. Read an excerpt of Colonel Lágrimas here.

Hanna Heiskanen (HH): Could you begin by describing your book to someone who doesn’t know anything about it?

Carlos Fonseca (CF): Imagine a book that works like a virtual map: you can zoom in or you can zoom out. If you zoom in, you will see the daily life of an eccentric old man who is constructing an encyclopedia of human knowledge. If you zoom out, you will see the political history of the twentieth century. Colonel Lágrimas tries to link these two narrative layers.

HH: This is your first novel—how did you get into writing fiction, and why did you want to tell this particular story?

CF: The novel sprang from two different events. The first is the moment in which a friend of mine tells me the life story of the eccentric mathematician Alexander Grothendieck, a brilliant thinker who ended up locked in his cabin in the French Pyrenees, imagining a universal theory of knowledge. The second was the moment I sat down and, influenced by the works of the American photorealist portrait painter Chuck Close, attempted to imagine what a close-up portrait of my character would “sound” like, what his voice would sound like. The moment I figured out which type of narrator I wanted, the novel’s structure became clear to me.

HH: History, its blurriness and dependence on perspective is one of the leading themes in your narrative. I understand your academic research also has to do with representations of history. How did your research seep into Colonel Lágrimas?

CF: I felt that the life of Alexander Grothendieck—upon which the character of the colonel is based—represented in some ways the history of the twentieth century: a century that began with an addiction to political action and ended up hooked on data. A century that moved from the battlefield to Wikipedia, so to speak. I wanted to explore, through the novel, this idea of contemporary history as a giant museum where the possibility of political action itself is at stake.

HH: You also write about how we can’t escape the inevitability of inheritance—“walking on a tightrope” means you can only walk in one direction—and whether it’s possible to change the narrative and thus the course of history.

CF: I think you are absolutely right: it is a novel about inheritance. A novel about what it means to inherit a history, a history both individual and communal. The protagonist, like Grothendieck, is the son of two left-wing anarchists and, as such, he must learn how to inherit this political tradition. In a way, I was interested in exploring the Colonel’s eccentric projects and actions as his way of appropriating the anarchist tradition from which he came. It is, indeed, a novel about the ways in which we narrate history and the consequences these narratives have upon us.

Borges, the Quixote, and Two Street Markets

The author of "The Antiquarian" tackles Borges, contextual understanding… and the singular joys of book shopping

The first time I read “Pierre Menard, author of the Quixote,” I was seventeen and in my freshman year in college in Lima. As anyone who reads Borges for the first time, I was dazzled by the story of a fictional French writer who, at the beginning of the twentieth century, wants to write once again, without plagiarizing or recovering it from memory, Cervantes’s Don Quixote. The most memorable passage of the story comes when the narrator, a friend of Menard’s, and very likely a French fascist, analyzes one paragraph from the novel in two different ways. First, assuming that Cervantes is the author, he concludes that the paragraph is rhetorical and verbose, when written by a seventeenth-century Spaniard. Later, assuming the author is Pierre Menard, a contemporary right-wing surrealist poet, he finds that the same words are fantastically counterintuitive and herald a new form of understanding the world. Since the narrator is a fascist, one suspects that his interpretation is an overinterpretation, the grotesque imposition of ideas that were not there in the original text.

READ MORE…

Contributor:- Gustavo Faverón Patriau

; Writers: - Gustavo Faverón Patriau

, - Jorge Luis Borges

; Tags: - Antiquarian

, - borges

, - Cervantes

, - commentary

, - fascism

, - Grove Atlantic

, - Gustavo Faverón Patriau

, - Latin America

, - Peru

, - Pierre Menard

, - Quixote

, - The Library of Babel