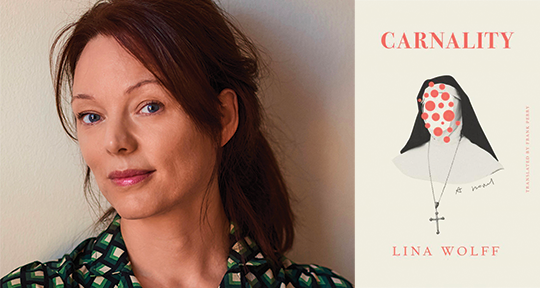

Carnality by Lina Wolff, translated from the Swedish by Frank Perry, Other Press, 2022

God was not really dead when Nietzsche proclaimed it through his speaking-box of Zarathustra. The sage of the German philosopher’s negations was, in fact, cementing the divine being in the noumenal; Nietzsche treated the death of God not as a state of things, but as a verb. It is not a death in the fact of non-existence, but an assassination. God is trapped in that liminal state of dying, and we are its killers, perpetuating the ongoing lineage of a refusal to believe. This is the way it was a hundred years ago, when atheism was radical and conscious, when a lack of faith had to make its way forward by obliteration, when such words had teeth.

In contrast, despite a nun being the prime orchestrator of events in Lina Wolff’s Carnality, God really does seem to be dead, a fact that no one fixates on because it would be like penning a manifesto of the Earth being round. Amidst the vast moral quandaries that swirl through the text, the ancient lessons and axioms that had once served as answers are nowhere to be seen, making room for that “ancient nobility” of chance to storm in between all those narrow spaces between us and the world, us and each other, us and ourselves. Adultery, caretaking, organ donation, euthanasia, murder—it’s all just happening. No choreography in the theatre of choice.

When a yet unnamed writer takes on a three-month travel grant in Madrid, she settles in the city the way one does in an airplane seat: procedural, passive, and with just a little bit of unarticulated dread. Having studied there in her youth, she is familiar with the city’s thorns and sieges, and from the first paragraph, we know—no one sane would choose to spend their summers in Spain’s capital. Still, small pockets of reprieve are there to be excavated: the ceaseless gurgles of wine pouring from dark bottles, the evening’s ink blotting some of the heat, the bright imagination of a city that holds newness in its oldness (“It’s down there. Life,” she thinks to herself). This transition of scenery outside the windows is settled quickly and efficiently in the space of a few pages, then Wolff draws the curtains, puts a drink in the narrator’s hand, and tunnels down into the strange, mutable basement-structure of story—a world which, its walls being made of words, shifts constantly with the mere logic of telling.