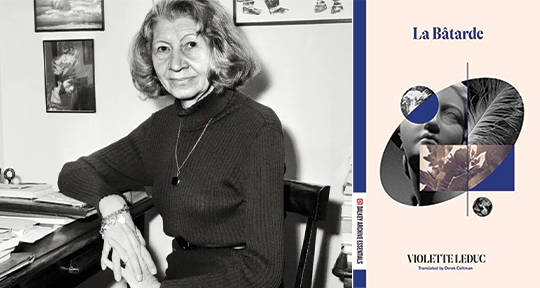

La Bâtarde by Violette Leduc, translated from the French by Derek Coltman, Dalkey Archive Press, 2023

“. . . very often, women think that all they need do is to tell their unhappy childhood. And so they tell it, and it has no literary value whatsoever, neither in style, nor in the universality which it ought to contain. So there are many, many autobiographies which publishers reject . . . Very disappointing . . . to think that as long as they’re women telling their story it will be interesting. . . . [but] there are extraordinary cases, like that of Violette Leduc who, exceptionally, was wonderfully successful.”

—Simone de Beauvoir, La Revue Littéraire des Femmes (March 1986)

“Being a woman, not wanting to be one,” Violette Leduc writes about her mother, Berthe, in La Bâtarde [The Bastard]. Perhaps she is speaking about herself as well, the reader takes a guess, which later in the autobiography is—spoiler alert—confirmed. Originally published in 1964 by Éditions Gallimard in Paris, La Bâtarde was translated into the English by Derek Coltman (who has translated two of her other works) as La Bâtarde: An Autobiography, and released the following year by C Nicholls & Company in the United Kingdom and by Farrar, Straus & Giroux in the United States. Over the years, at least two new editions have been published, and this year, we are given a new edition to this bestselling French autobiography from Dalkey Archive Press.

“Being a woman and therefore condemned to the miseries of the feminine condition,” echoes Simone de Beauvoir in the foreword. Like Hannah Arendt, Frantz Fanon, Robert Brasillach, and Richard Wright, Leduc is considered a historical contemporary and political protege of Beauvoir (although ecofeminist-biographer Françoise d’Eaubonne disagrees, stating that Leduc never subscribed to Beauvoir’s philosophy or politics). It may have been, however, more than that; newly discovered letters—two hundred and ninety-seven of them—have revealed Beauvoir rejecting Leduc’s repeated romantic advances.

This autobiography is unapologetic—particularly so, as Laetitia Hanin deems, because while its predecessors within Francophone women’s literature, like the memoirs of George Sand and Marie d’Agoult, sacrificed to self-mythification, Leduc did not apologise for writing the story of her life. Beginning in northern France, the author reveals a childhood spent under WWI German occupation, where the government’s rationing of food is so insufficient people resorted to stealing cabbages from the back of carts. Two maternal figures among a neighbourhood of women raise her: her mother, Berthe, with whom she has an extremely agonising and suffocating relationship (“You were all I had, mother, and you wanted me to die with you”); and her grandmother, Fidéline, “an angel” who loved her “in passionate silence.” In her youth, as an “unrecognized daughter of a son of a good family,” she yearns for a paternal figure, but she will never know her father André, a man whose dominant quality is anonymity: “It is a strange moment when you gaze questioningly at an unknown figure in a picture and the picture, the unknown figure, is your nerves, your joints, your spinal column.” Further contemplating on her lineage, Leduc writes, “I reject my heredity.” This is particularly true with her maternal relationship, when in the later years Leduc would say: “Her absence was a relief; I was oppressed by her return.” Eventually, she would burn André’s photograph along with his death certificate. She writes, “My birth is not a matter of rejoicing.”