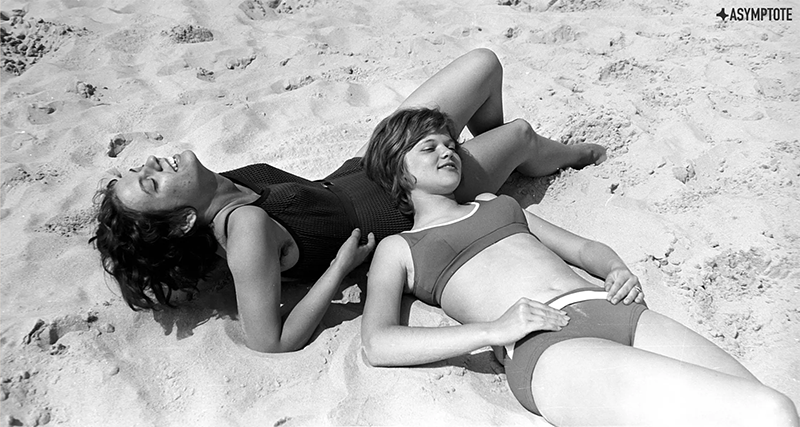

The fall of the Berlin Wall catalysed a monumental case of political integration in the West, heralding a necessary conciliation of disparate politics, economics, psychologies, values, and socialities. Of this time, the grand dialogues and negotiations between international governmental bodies are well-documented and enshrined in textbooks, but the stories of ordinary lives swept up in this extraordinary fusion are still in the middle of being told, processed, and understood. One of the most subtle—yet enduring—issues is the distinct views of sexuality and intimacy in the two Germanies, which reflects the greater ideological differences in both unpredictable and surprising ways. In the following essay, Moumita Ghosh takes a look at two contemporary novels that feature romantic relationships under the political influence, Jenny Erpenbeck’s Kairos and Ralf Rothmann’s Fire Doesn’t Burn, illustrating how the quakes of national movements send their aftershocks into our most private spheres.

Still, there is one thing they still do that hasn’t changed: when they leave a place together, he holds out her coat, she slips into it frontwise, briefly holds him in her arms, then slips it off and puts it on the right way around. But probably, even these habits, in which they took pleasure and pride, and which confirmed their intimacy, are nothing more than a hollow-bellied Trojan horse.

—Jenny Erpenbeck, Kairos

Jenny Erpenbeck’s Kairos, winner of the International Booker Prize in 2024, sketches a tumultuous romance between Katharina, a young woman, and Hans, a married man thirty-four years her senior. Translated by Michael Hofmann and set in 80s Germany, the text intertwines the couple’s intimate narrative with national history. Hans, his childhood overcast by the Hitler Youth and his father’s Nazi sympathies, is eventually revealed to be a Stasi informant, having ‘decided in favour of that part of Germany that had Anti-Fascism written on its red banners.’ Katharina, in contrast, was born after the war and is characterised by a certain political apathy despite her youth; rather, she comes across as a citizen of the imminent reunification. When she travels to the West for an internship in Frankfurt and gets romantically involved with a colleague, this fluidity of her character becomes even more apparent. As her interactions with Vadim, her colleague, progresses slowly and spontaneously, her relationship with Hans becomes even more stifling and unnatural—and what comes across as the modern sexual mores of East Germany soon reveal themselves to have sinister tones. Intimacies begin to mirror political realities as Hans becomes more controlling with Katharina—a danger that has subtly existed since the beginning of their acquaintance. Eventually, their relationship becomes a surrogate of East Germany, where sexual liberation sat uncomfortably with repressive surveillance, while their devolving affinity also collaterally communicates the decaying of the present and the transition towards reunification.