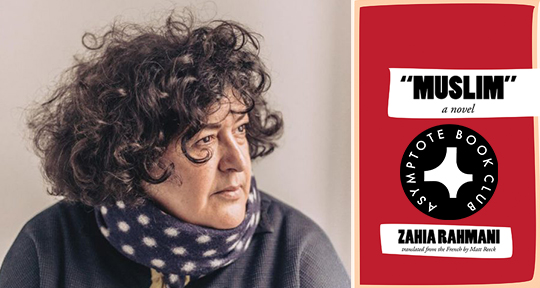

Zahia Rahmani’s “Muslim”: A Novel (translated into English by Matt Reeck and published by Deep Vellum) is a combination of fiction and essay, written with a “stark and uncompromising beauty.” When the novel was first excerpted in Asymptote back in 2015, Matt Reeck highlighted the way in which “The novel’s experimental form stages the gaps between places, and between accepted norms, where a person cast adrift must live.”

Now, Asymptote Book Club subscribers will have a chance to discover this “contemporary classic” in full. You can join our discussion on the Asymptote Book Club Facebook group, or sign up to receive next month’s title via our website.

“Muslim”: A Novel by Zahia Rahmani, translated from the French by Matt Reeck, Deep Vellum, 2019

Reviewed by Erik Noonan, Assistant Editor

The protagonist of Zahia Rahmani’s “Muslim”: A Novel has lived a life contained within the constraints of a pair of quotation marks. The exercise of her voice in the printed word—French in the original, English in a new translation by Matt Reeck—represents an effort to outtalk the multitude that would mischaracterize her and confine her to a type. She speaks out even though her efforts to liberate herself have only shrunk the bounds of her freedom.