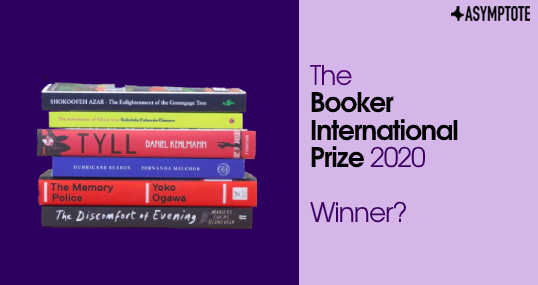

The long-awaited announcement of the International Booker winner is finally around the corner, and with a shortlist explosive with singular talent, the gamblers amongst us are finding it difficult to place their bets. To lend a hand, Asymptote’s very own assistant editor Barbara Halla returns with her regularly scheduled take, lending her scrupulous gaze to not only the titles but the Prize itself—and the principles of literary criticism and merit.

In my previous coverage of the International Booker Prize, I mentioned that there is always an element of repetition to the discussions surrounding it; quite honestly, there are only so many ways one can frame the conversation beyond mere summarizations of the books themselves. I find myself hoping that each year’s selections will reveal some sort of larger theme looming in the background, giving me at least the pretense of a cohesive thesis statement. I think that was definitely the case with last year’s shortlist and its explicit concern with memory, but considering how English translation tends to lag behind each book’s original publication by at least a couple of years, it was probably a coincidence. I’ve had no such luck with the 2020 shortlist; most of my attempts at finding a common theme have felt like a stretch.

In an attempt to avoid making this simply a collection of bite-sized reviews, I want to talk about one of my least favorite strands of Booker discourse: the tedious—sometimes almost malicious—assertion that if a particular book wins, it does so not because of its “literary merit,” but rather because it ticks a number of marketing-friendly boxes. Maybe it has been translated from a language that rarely gets published in English, or perhaps it seems particularly relevant to our present, directly tackling racism, homophobia, or misogyny. Regardless of the source of such a statement, it has this irritating “political correctness is ruining literature” thrust to it.

Now, in the past I have relied on “non-literary” clues to try and guess the Booker winner, and to some extent, I still do. However, in my mind, whenever I try to glean the winner using such external factors, I do so based on a few assumptions. First of all, while not all shortlisted books will necessarily be my favorite or even to my liking, the judges at least believe them to be great books, and the winner might indeed be different under different (personal) circumstances. In fact, despite what some detractors of contemporary fiction might say, there is plenty to love about the books being published today, and in the presence of so much good literature, taking into account “external” factors is only natural. After all, as translator Anton Hur recently tweeted, in response to an article arguing against a translated fiction category for the Hugos, “Literary awards ARE marketing tools, they should be used to solve MARKETING PROBLEMS.” READ MORE…