From our Winter 2024 issue, Palestinian poet Samer Abu Hawwash’s “My People”, translated by Huda J. Fakhreddine, was voted the number one piece by our internal team. It’s easy to understand why—not only is the poem a stunning work that aligns its vivid, rhythmic language with the devastations and violences of our present moment, it is also translated with great sensitivity and emotionality into an English that corresponds with a tremendous inherited archive, and all the individuals who are keeping it—and the landscape—alive. In the following interview, Fakhreddine speaks to us about how this poem moves from hopelessness to resistance, from the great wound of war to the intimate determinations of the Palestinian people.

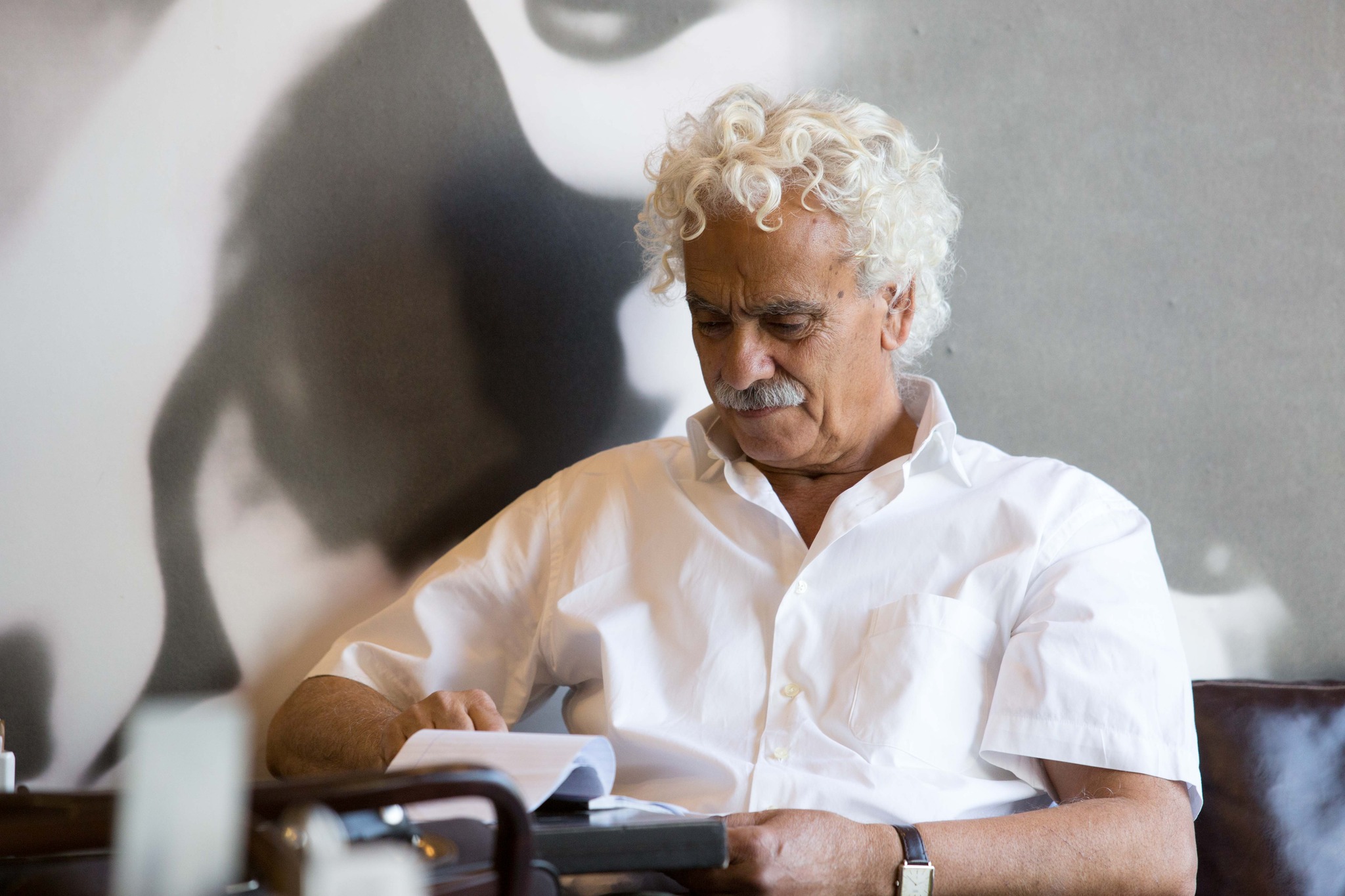

Sebastián Sánchez (SS): Reading your translation of Samer Abu Hawwash’s “My People” is striking, as one gets the sense that this is the closest we might get to putting into words the unspeakable horror that is occurring currently in Gaza. What led you to decide to translate this poem in particular? What was your relationship with Hawwash’s work before you decided to translate “My People”?

Huda J. Fakhreddine (HJF): I have been unable to do anything other than follow the news from Gaza and try my best to stay afloat in these dark times, especially when I, and others like me in American institutions, are facing pressures and intimidation for merely protesting this ongoing genocide. Since last fall, we have been threatened and exposed to vicious campaigns for merely celebrating Palestinian literature and studying Arabic culture with integrity. If we accept the fact that we are expected to be silent when more than 30,000 Palestinians are genocidally murdered, and accept the false claim that this does not necessarily fall within the purview of our intellectual interests, we are nothing but hypocrites and opportunists.

I find a selfish consolation amid all this in translating poems from and about Gaza. I need these poems. They don’t need me. Samer shared this poem with me before he published it in Arabic, and it arrested me. It so simply and directly contends with the unspeakable, with the horrifying facts of the Palestinian experience. Samer confronts the unspeakable head on and spells it out as a matter of fact. This paradox of a reality that is at once unimaginable and a matter of fact is what makes this poem. Samer achieves poetry with a simple, unpretentious language like a clear pane of glass that frames a scene, arranges it, and transparently lets it speak for itself.