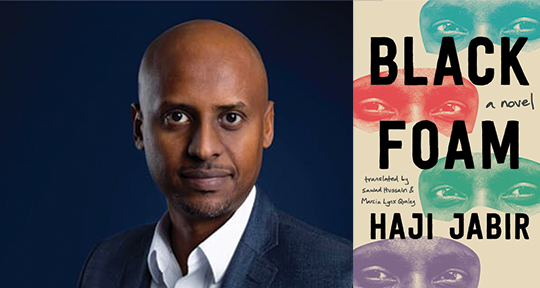

Black Foam by Haji Jabir, translated from the Arabic by Sawad Hussain and Marcia Lynx Qualey, Amazon Crossing, 2023

In a 2019 interview with Marcia Lynx Qualey for Arab Lit, Haji Jabir gives a fascinating response when asked whether he writes “political novels”: “I write about the people of my country, because they are a persecuted and suffering people, and so my novels come in this manner. I would like to write far from politics, but I would betray these people if I turned away from their issues.” At the time of the interview, Jabir had recently published (رغوة سوداء (2018), which has now been jointly translated into English as Black Foam by Sawad Hussain and Qualey. The novel follows an Eritrean man on a journey to find his place in the world, and as he uneasily moves from one location to the next, unable to find a place where he can lay down roots, he changes names and identities fluidly in order to fit in, to have a better chance at a new life.

Given the name Adal at birth (or so he says), he claims to be a ‘Free Gadli’, the Eritrean term for children “born of a relationship between soldiers on the battlefield that goes against religious law.” The Eritrean War for Independence against Ethiopia went on from 1961 to 1991 and Adal, by his admission, was born during this conflict, growing into a seventeen-year-old soldier when Eritrea was finally liberated. To avoid the association with “Free Gadli” in the post-war nation, he changes his name to Dawoud. He is then sent to the Blue Valley prison camp for infarctions committed when he is supposed to be in the Revolution School, but when he supposedly escapes—though he never divulges how—to the Endabaguna refugee camp in Northern Ethiopia, he becomes David. From there, he manages to enter the Gondar camp by posing as a Falash Mura named Dawit, and gets resettled in Israel. These changing names indicate transformation by association, from a Muslim to a Christian to a Jew.

In inscribing his protagonist with an ever-shifting self, Jabir asserts that stories are a potent tool for self-fashioning; they dictate affiliations and guide assimilations, helping Adal become whoever he needs to be at that very moment. The oral traditions of storytelling are further reflected in the way the novel is structured. The narrative is circuitous and fluid, the chapters quickly moving between the past and present in order to flesh out details, with the name Adal uses as the quickest identifier of time and place. In Jerusalem, during an interview with a sociologist, he is asked which of his three names he prefers: “Should he say Dawoud, with all the defeats and losses that old name carried? Or should he choose David, a newer name, yet with as many bitter experiences? Or should he stick with the infant Dawit, without knowing for sure whether it was any different from its predecessors?” Seemingly a simple question, it clearly throws him into existential confusion. READ MORE…