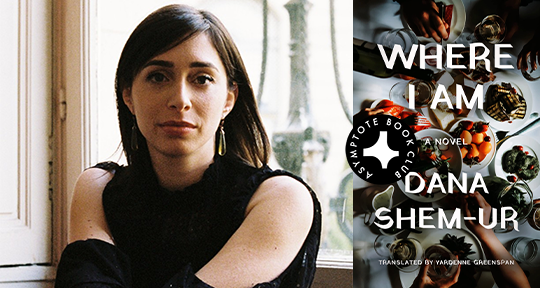

Our June Book Club selection, Dana Shem-Ur’s Where I Am, is a novel that looks intensely at the dissonances of daily life in the aftermath of migrancy, profoundly reaching below the surface of superficial comfort to read the disassociations and discontents that stem from being not quite in-place. Reaching into the mind of an Israeli translator named Reut who has settled in France, Shem-Ur constructs a map of navigations amidst cultural codes, languages, and physical agitations, drawing out the anxiety of belonging. In this interview, we speak to Shem-Ur and translator Yardenne Greenspan about this novel’s simmering frustrations and the new Israeli diaspora, and how they have both used language to reflect the confounding boundaries of our social fabric.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

Laurel Taylor (LT): Dana, I’d like to ask you about what sparked the creation of this novel—particularly as you’re already a translator and scholar. How did Where I Am come about?

Dana Shem-Ur (DS): I come from a family of a female authors. My mom is a poet, and my grandma wrote over thirty books, so I always was involved in this world. In fact, when I was little, I didn’t even read a lot. I just wrote fiction, and even published a small novella of one hundred pages when I was about twelve.

Then I dropped it because I was engaged in studying history, and I channeled my life of writing into other domains. It was only later on, when I was in Paris for three years for my master’s degree in philosophy, that I just came home one summer and wrote the first few pages.

I think what generated this novel was my certainty that I would remain in France, and I would have a life there. I began writing this story about a woman who is twenty years older than me and lives in Paris, but she’s unhappy, and I think part of it was just a reflection of my fears. What will become of me? Will I become Reut?

LT: It’s almost like speculative autofiction?

DS: Yeah. I didn’t even notice it when I wrote it, but it was also inspired by a lot of characters that I met. No character in Where I Am is a real person, but the salon of people at the Jean-Claude household are all inspired by people I met and by these talks and these Parisian intellects, who I always found very fascinating; they are my friends, but throughout the period I lived there, I felt there was a barrier between us. I was always the observer who was looking at this spectacle, not completely present, like Reut. I’m very fascinated by foreign cultures, so it felt like something I needed to write about. READ MORE…