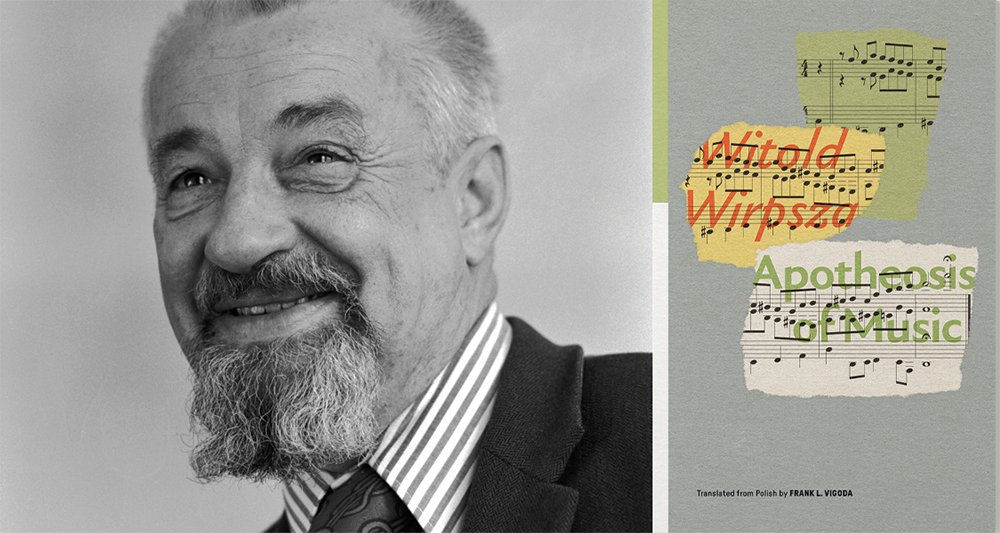

Apotheosis of Music by Witold Wirpsza, translated from the Polish by Frank L. Vigoda, World Poetry, 2025

In the fourteenth century, writing from a state of political exile from Florence, Dante gave us an allegorical tour of the afterlife with an imaginary Virgil as his guide, presenting a cast of historical and mythic figures re-imagined. It isn’t hard to make the connection between him and the twentieth-century Polish poet Witold Wirpsza, who, as he contended with World War II and its subsequent outfalls, wrote from a state of exile in West Berlin and introduced his own cast of mythic figures: Dante, Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Stalin. Now, from Frank L. Vigoda—the nom de plume of translator husband-wife duo Gwido Zlatkes and Ann Frenkel—comes Apotheosis of Music, a selection of Wirpsza’s cerebral and exuberant oeuvre in an indulgent, cheeky, rhythmic English, at times originating its own pleasant musicality. Where Zlatkes lends his native Polish perspective, Frenkel’s background in musicology allows for an execution of the musical structures and themes prevalent throughout Wirpsza’s work.

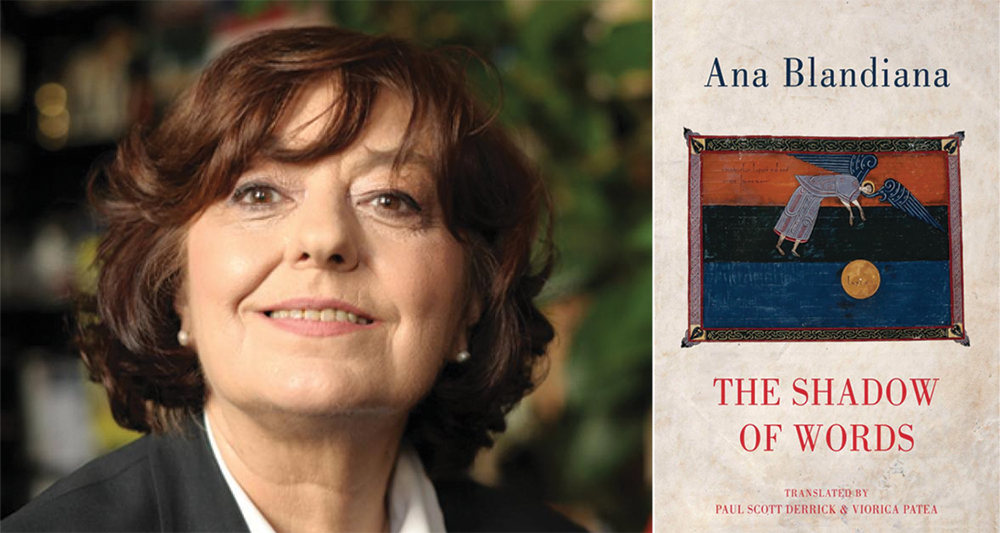

Born in Gdańsk, Poland in 1918 and educated in music and law, Wirpsza was drafted into WWII, held as a prisoner of war in a German camp, and, after initially being a supporter of communism following the war, eventually defected from the Polish United Workers Party (PZPR) in objection to its policies. After publishing an essay critiquing nationalist identities called “Polaku, kim jesteś” (Pole, who are you), he was banned from publication in his native Poland—a sentence that lasted until 1989, four years after his death. He then settled in West Berlin, where he lived for the remainder of his life; there, he brought works of Polish literature to a German audience and vice versa, translating works like a biography of Bach and a novel about Mozart from German into Polish. READ MORE…