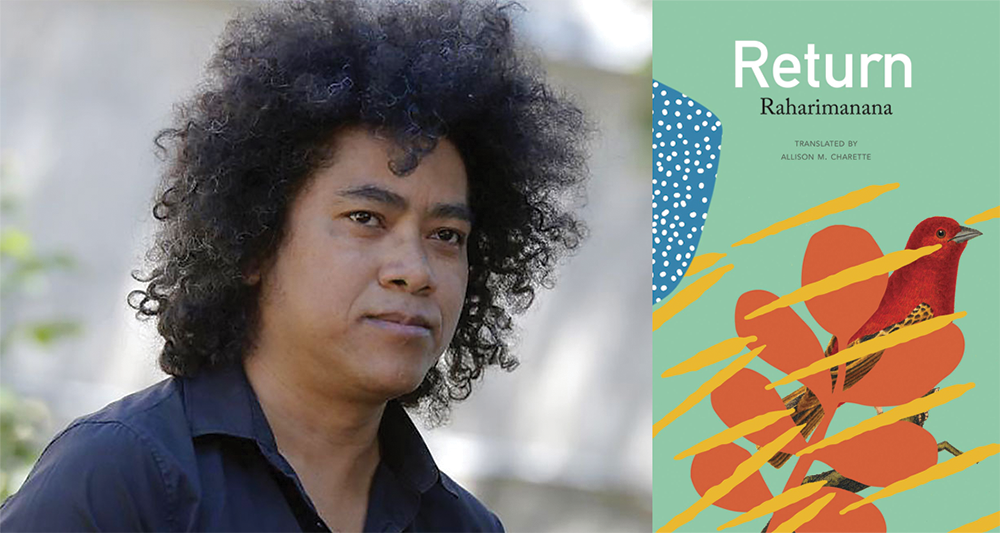

Return by Raharimanana, translated from the French by Allison M. Charette, Seagull Books, 2025

A newly independent nation. The visions of building. The sacrifices, people, losses. If this invigorating spirit is unwaveringly intoxicating, its effects are as much generational as they manifest in the present. In his novel Return, Raharimanana knits together a young man’s memories of his father and the spirituous strides taken to uphold truth against power in the aftermath of colonialism—specifically when the nascent country of Madagascar erupted in revolution in 1972 after gaining independence from the French in 1960. Hira, around whom much of the story revolves, is hailed as an oscillatory reminder of the time since Madagascar’s freedom, forming an autobiographical arc in Raharimanana’s own reconciliation with his childhood. The author’s writing also carries the artfulness of music, an art that he engages in alongside being a novelist, poet, and playwright.

In an earlier book, Nour 1947 (2001), Raharimanana penned a closer engagement with the 1947 Malagasy Uprising, dealing with the deadly killings of 87,000 Malagasys by the French colonial rule. Return, which was first published in 2018 in French as Revenir, now puts on a vivid image of Hira’s life as a touring writer and his recollections of the transitioning state of Madagascar. As he travels, he is disturbingly reminded of his father’s torture and the price paid by his family, and these fragmented recollections do not let him collate a neat history. Hence, the sections of the present are reeling with the irredeemability of time, a fracturedness that also speaks to the inability to write of a violence that is both collective and overpowering. As the novel moves on, this position culminates into renewed impetus for his writing, rife with image and poetic terseness. Being born after independence, Hira is part of a nation attempting to blossom a life out of the ruins—and this is true for Hira’s own family as well as for the country. For him, it is tiring: “But also weariness. He’d had enough of all of that. Being confronted with his country’s violence.” READ MORE…