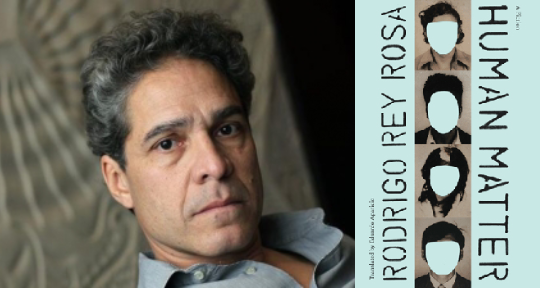

Human Matter: A Fiction by Rodrigo Rey Rosa, translated from the Spanish by Eduardo Aparicio, University of Texas Press, 2019

As noted over the years by scholars such as Arturo Arias, Central American cultural production remains largely at the margins of academic study. As Arias points out in Taking Their Word, because popular knowledge of the region is so sparse, and because geographic ignorance (particularly in the United States) is so widespread, Central American immigrants will often identify Mexico as their country of origin, both for reasons of Latinx solidarity, and to protect themselves from discrimination and prejudice. This erasure is not even a recent phenomenon: the protagonists of the 1983 film El Norte, the Guatemalan-Maya brother and sister Enrique and Rosa Xuncax, are told to tell people that they are from the heavily Indigenous state of Oaxaca, Mexico, to avoid being taken advantage of in both Mexico and the US. However, from the United Fruit Company in the early twentieth century to the practices of Canadian mining companies, and even US president Donald Trump’s facilitating, in the words of the Guatemalan-American author Francisco Goldman, “organized crime” in Guatemala’s 2019 presidential elections, global forces have always played, and continue to play, an outsized role in the region.

Despite its apparently marginal status, the region has made a number of enduring contributions to world literature. Foremost among them is one of the fathers of Latin American modernism, the Nicaraguan Rubén Darío, and the Guatemalan Nobel Laureate Miguel Ángel Asturias, not to mention one of the most important works of Indigenous literature in the Americas, the K’iche’ Maya Popol Wuj. Outside of these points of reference, however, much of the region’s vast, rich literature remains untranslated, which makes Eduardo Aparicio’s translation of Rodrigo Rey Rosa’s El material humano as Human Matter all the more important.

Rey Rosa, perhaps Guatemala’s most important living novelist, has had an eclectic literary trajectory. Having gone to New York in the early 1980s, he eventually became the protégé of the US-expatriate author Paul Bowles, spending a good deal of time with the author in his adopted home of Tangier, Morocco, and even becoming executor of Bowles’s literary estate upon the author’s death in 1999. Tellingly, one of Rey Rosa’s previously translated novels, the magnificent The African Shore, deals with the intersection of tourism, privilege, and migration in the border zone not between Guatemala and the US, or even between Guatemala and México, but between Morocco and Spain.

READ MORE…