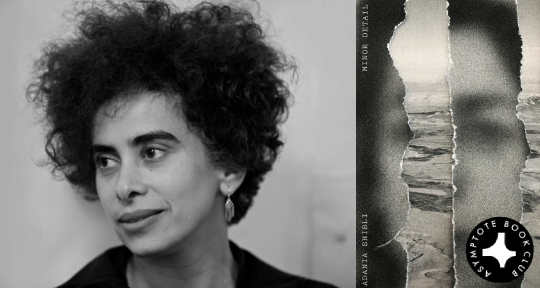

One of the most powerful responsibilities of literature is to ascribe human voices to the momentous, overarching events of our world. This month, Asymptote has selected Adania Shibli’s unflinchingly powerful Minor Detail, a novelistic reflection on the violent and painful consequences of the Israeli-Palestinian conflicts, from the War of 1948 to present day. With an astutely visual language and an unwaveringly intelligent morality, Shibli’s work is an impeccably crafted totem of resistance and justice.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD15 per book; once you’re a member, you can join the online discussion on our Facebook page!

Minor Detail by Adania Shibli, translated from the Arabic by Elisabeth Jaquette, New Directions (US), Fitzcarraldo (UK), Text Publishing (Australia), 2020

The smell of gasoline, the sound of a dog howling, the taste (or distraction) of a simple stick of chewing gum—these are only a few of the motifs surrounding trauma and pain in Minor Detail, by Adania Shibli, translated from the Arabic by Elisabeth Jaquette. It is August, 1949, and a group of Israeli soldiers have set up camp in the Negev desert. As they patrol the nearby areas, they encounter and ambush a group of Bedouins, returning with a single survivor: a young Arab woman. Shortly after, she is hosed down and raped by the officer in charge. Over half a century later, a woman living in the West Bank crosses the border into Israel, looking to uncover the details of the case. Her journey reflects a changed Middle East.

As a literary project, a historical record, and a translation, Minor Detail is, simply put, brilliant. My knowledge of the Arabic language is limited, and so my goal here isn’t to compare the translation to the original text. Instead, I want to focus on narrative structure and style—two elements clearly on the minds of both Shibli and Jaquette, whose collaboration proves a success on all fronts.