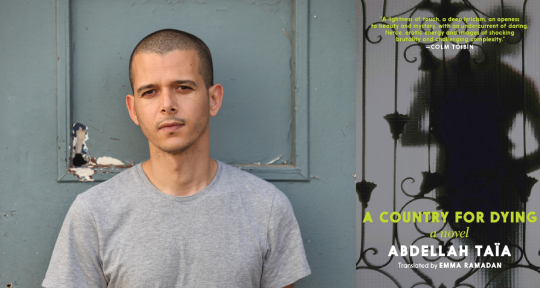

A Country for Dying by Abdellah Taïa, translated from the French by Emma Ramadan, Seven Stories, 2020

A Country for Dying is more about atmosphere than plot. It is a brief, taut work that digs deep into the margins of society to demonstrate the many ways in which colonialism pollutes our notions of love and self. Over the course of three parts and six chapters, Abdellah Taïa introduces us to the inner lives of four immigrants in Paris, as they contend with their present realities, the pasts they are trying to flee, and the dreams they still hope to indulge.

Their stories read like monologues, and talk toward each other more than they ever intersect. In this they mimic the characters, who are largely confined to their individual apartments; even the city that holds them all is, in a way, isolating—a refuge that can never quite be home (as a Moroccan living in Paris, Taïa himself writes from a place of exile). Thus, while each narrative voice is unique, they all share a sense of loss. A Country for Dying draws its strength from its haunting air of solitude.

If there’s anything like a connective tissue between the stories, it is Zahira: a forty-year-old Moroccan sex worker who has moved to Paris to escape the trauma of her father’s suicide when she was a girl. She struggles with the guilt of having “abandoned” him when he fell ill and was confined to the second floor of their house. “I didn’t think my father was going to die,” she reflects, “[b]ut I accepted, just like everyone else, that I wouldn’t see him again . . . The weight of his heavy footsteps echoes in my ear.” Grief-stricken, Zahira struggles to rewrite his story and heal her pain. Much of the chapter devoted to it is written in the second person as she addresses her father directly, updating him on his family’s lives after his death; in practice, however, it feels like she is addressing the reader, telling us her story on her own terms, to great emotional effect.

There is a direct through line between Zahira’s trauma and her instinct to take care of Mojtaba, a gay Iranian exile, when she finds him collapsed on the street. Looking after him over Ramadan helps her cope with her father’s death: “He was also tender, sweet, melancholic. That was obvious immediately. Something in him was similar to me, familiar.” For a moment, the quiet intimacy that forms between them brings them the peace they so badly deserve. Their bond never ceases to feel fragile, though, and it is clear that it will not last. READ MORE…

Announcing our August Book Club Selection: People From My Neighborhood by Hiromi Kawakami

The portrayal and analysis of collective experience makes this a text that truly meets our moment.

As we continue into the latter half of this increasingly surreal year, one finds the need for a little magic. Thus it is with a feeling of great timeliness that we present our Book Club selection for the month of August, the well-loved Hiromi Kawakami’s new fiction collection, People From My Neighborhood. In turns enigmatic and poignant, as puzzling as it is profound, Kawakami’s readily quiet, pondering work is devoted to the way our human patterns may be spliced through with intrigue, strangeness, and fantasy; amongst these intersections of normality and sublimity one finds a great and wandering beauty.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD15 per book; once you’re a member, you can join the online discussion on our Facebook page!

People From My Neighbourhood by Hiromi Kawakami, translated from the Japanese by Ted Goossen, Granta, 2020

Like a box of chocolates, Hiromi Kawakami’s People From My Neighbourhood (translated from the Japanese by Ted Goossen) contains an assortment of bite-sized delights, each distinct yet related. This peculiar collection of flash fiction paints a portrait of exactly what the title suggests—the denizens of the narrator’s neighborhood—while striking a perfect balance between intriguing specificity and beguiling universality. The opening chapters introduce readers to each of the neighborhood’s curious inhabitants, while later chapters build upon the foundation, gradually erecting a universe of complex human relationships, rigorous social commentary, immense beauty, and more than a little magic.

Existing fans of Kawakami’s will surely recognize these common features of her award-winning body of work, while first-time readers will likely go searching for more. Goossen is better known as a translator of Murakami and editor of the English version of the Japanese literary magazine MONKEY: New Writing from Japan (formerly Monkey Business); ever committed to introducing Anglophone readers to non-canonical Japanese writers, he brings his flair for nonchalant magical realism to this winning new collaboration.

The first story, “The Secret,” introduces readers to the anonymous narrator and sets the tone for the collection. First presented as genderless, (we only find out later that she is female) she discovers an androgynous child, who turns out to be male, under a white blanket in a park. The child, wild and independent, comes home with her. Despite occasional disappearances, he keeps her company as she ages, all the while remaining a child. In this story, we receive her only concrete—but general—description of herself: “I’ve come to realize that he can’t be human after all, seeing how he’s stayed the same all these years. Humans change over time. I certainly have. I’ve aged and become grumpy. But I’ve come to love him, though I didn’t at first.” This one statement exemplifies many of the collection’s trademark characteristics and overarching themes: a version of time in which past, present, and eternity coexist, the supernatural, and the narrator’s fascinating method of characterization. READ MORE…

Contributor:- Lindsay Semel

; Language: - Japanese

; Place: - Japan

; Writer: - Hiromi Kawakami

; Tags: - family

, - fantasy

, - Japanese literature

, - Magical Realism

, - social commentary

, - strangeness

, - Women Writers