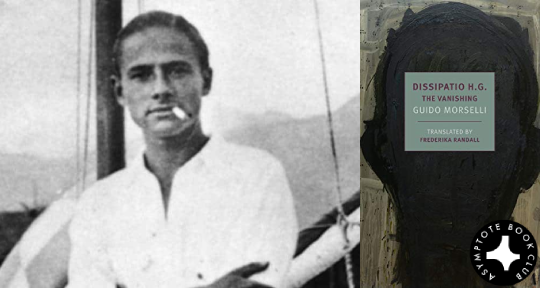

Quietly, almost as if afraid to disturb, a new year has made its way into the world. The recession of 2020 into the distance of the past presents an opportunity to not only evaluate the changed world, but also to contemplate our responsibilities in readjusting, amending, and moving on. In a fitting selection, our last Book Club title of 2020 is Guido Morselli’s acclaimed novel, Dissipatio H.G., a text that reconciles the stark realities of mourning with poignant examinations of presence in and amidst so much absence. It is a rare feeling that has somehow, incredibly, become common: What is one to do upon waking up to an unrecognizable world?

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD15 per book; once you’re a member, you can join the online discussion on our Facebook page!

Dissipatio H.G. by Guido Morselli, translated from the Italian by Frederika Randall, New York Review Books Classics, 2020

Near the outset of Guido Morselli’s short and surreal 1977 novel, Dissipatio H.G., the unnamed narrator sits in a cave at the edge of a steep drop into an underground lake, getting up the nerve to end it all. Meanwhile, down in the valley, in the invented, industrious city of Chrysopolis, the economy booms, not unlike the growth Morselli observed in post-war Italy. Leery of society’s so-called progress, the narrator has retreated to an isolated property in the mountains—but even that is threatened; he’s pushed to the lip of nonexistence when he finds a cluster of numbered stakes in the ground “a couple of hundred paces from my mountain retreat.” After a fever and a frantic investigation, he uncovers that a company plans to build a highway there, complete with entrance ramps, a cloverleaf, and a motel. “As Durkheim might say,” the narrator reflects, “there’s your trigger.”

In the end, he abandons his plan after contemplating the quality of the Spanish brandy he’s brought along for liquid courage. His body’s physical matter simply refuses to accede to his will; he bangs his head on the way out of the cave, just as a powerful groan of thunder rolls through the valley. “The truth is,” he thinks, “a man who draws back from killing himself does so (and Durkheim didn’t see this) under the illusion that there is a third way, but in fact tertium non datur—there is no third possibility: it’s either a leap into the siphon or a dive back into daily life, where the rhythm of everything has stayed exactly as it was and you must hasten to make up for the progress lost.”

But when he returns from the cave, the narrator discovers an entirely unexpected third possibility: while he has chosen to live, the human race has vanished. He inspects the newsroom where he once worked as a journalist, placing calls across Europe and across the Atlantic to determine that for all functional purposes, he is the last man alive. “I’m now Mankind,” he says. “I’m Society (with the capital M and the capital S).” He is, he says, “Incarnation of the epilogue.” READ MORE…