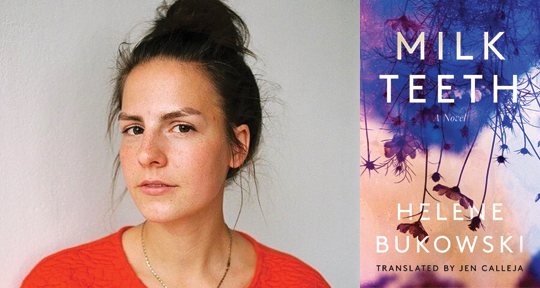

Milk Teeth by Helene Bukowski, translated from the German by Jen Calleja, Unnamed Press, 2021

You can’t expect the world to be exactly the same as it is in books.

Milk Teeth is claustrophobic. The silent world of Skalde and her mother Edith is cut off from everything else by fog and a collapsed bridge; civilization has also crumbled, and they reside in its remnants on the edge of a small, loosely-knit group in a so-called ‘territory.’ Edith has arrived in this place as an outsider, so though they are treated with tolerance, still disdain and suspicion dominate their relationships with most of the few people they have any contact with. In this fearful landscape, Skalde loses herself in books—until the day she starts losing her milk teeth, and finds a girl in the forest called Meisis. Thereafter, she slowly finds the strength to rebel against her mother’s neglect, and to question the rules of the society she finds herself in.

As a child, Skalde rarely leaves her house and garden, bringing it to close relevance with our era, and the all-too-familiar confinement common to all of us. The world beyond the river is depicted as a scary, dangerous place that presses at the edges of their small existence, serving as a further reminder that we are living in an increasingly atomised age—an era of isolationism between nations sparked by telltale international shifts to the political right, along with increasingly popular feelings amongst world leaders that their ‘country is an island’—catalysed by COVID.

In the ‘territory,’ the suspicion of outsiders is overarching, echoing the eagerness of some to designate certain groups as responsible for their hardships. Half-truths and disinformation are rife; neighbours judge neighbours, and people are cast out for reasons as trivial as having red hair or failing to lose their milk teeth. The setting—dense fog followed by blazing heat in an indiscernible survivalist purgatory—only adds to the novel’s cloying nature. Reading this during quarantine felt akin to falling through the looking glass into a world only slightly more absurd than our own. READ MORE…

What’s New in Translation: August 2021

New work this month from Lebanon and India!

The speed by which text travels is both a great fortune and a conundrum of our present days. As information and knowledge are transmitted in unthinkable immediacy, our capacity for receiving and comprehending worldly events is continuously challenged and reconstituted. It is, then, a great privilege to be able to sit down with a book that coherently and absorbingly sorts through the things that have happened. This month, we bring you two works that deal with the events of history with both clarity and intimacy. One a compelling, diaristic account of the devastating Beirut explosion of last year, and one a sensitive, sensual novel that delves into a woman’s life as she carries the trauma of Indian Partition. Read on to find out more.

Beirut 2020: Diary of the Collapse by Charif Majdalani, translated from French by Ruth Diver, Other Press, 2021

Review by Alex Tan, Assistant Editor

There’s a peculiar whiplash that comes from seeing the words “social distancing” in a newly published book, even if—as in the case of Charif Majdalani’s Beirut 2020: Diary of the Collapse—the reader is primed from the outset to anticipate an account of the pandemic’s devastations. For anyone to claim the discernment of hindsight feels all too premature—wrong, even, when there isn’t yet an aftermath to speak from.

But Majdalani’s testimony of disintegration, a compelling mélange of memoir and historical reckoning in Ruth Diver’s clear-eyed English translation, contains no such pretension. In the collective memory of 2020 as experienced by those in Beirut, Lebanon, the COVID-19 pandemic serves merely as stage lighting. It casts its eerie glow on the far deeper fractures within a country riven by “untrammelled liberalism” and “the endemic corruption of the ruling classes.”

Majdalani is great at conjuring an atmosphere of unease, the sense that something is about to give. And something, indeed, does; on August 4, 2020, a massive explosion of ammonium nitrate at the Port of Beirut shattered the lives of hundreds of thousands of people. A whole city collapsed, Majdalani repeatedly emphasises, in all of five seconds.

That cataclysmic event structures the diary’s chronology. Regardless of how much one knows of Lebanon’s troubled past, the succession of dates gathers an ominous velocity, hurtling toward its doomed end. Yet the text’s desultory form, delivering in poignant fragments day by elastic day, hour by ordinary hour, preserves an essential uncertainty—perhaps even a hope that the future might yet be otherwise.

Like the diary-writer, we intimate that the centre cannot hold, but cannot pinpoint exactly where or how. It is customary, in Lebanon, for things to be falling apart. Majdalani directs paranoia at opaque machinations first designated as mechanisms of “chance,” and later diagnosed as the “excessive factionalism” of a “caste of oligarchs in power.” Elsewhere, he christens them “warlords.” The two are practically synonymous in the book’s moral universe. Indeed, Beirut 2020’s lexicon frequently relies, for figures of powerlessness and governmental conspiracy, on a pantheon of supernatural beings. Soothsayers, Homeric gods, djinn, and ghosts make cameos in its metaphorical phantasmagoria. In the face of the indifferent quasi-divine, Lebanon’s lesser inhabitants can only speculate endlessly about the “shameless lies and pantomimes” produced with impunity. READ MORE…

Contributors:- Alex Tan

, - Fairuza Hanun

; Languages: - French

, - Hindi

; Places: - India

, - Lebanon

; Writers: - Charif Majdalani

, - Geetanjali Shree

; Tags: - Beirut 2020 explosion

, - diary

, - disaster

, - Indian Partition

, - motherhood

, - recovery

, - social commentary

, - trauma

, - womanhood