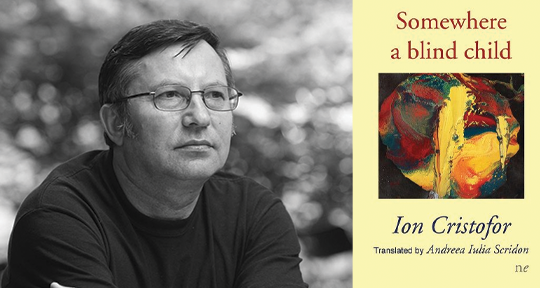

Somewhere a Blind Child by Ion Cristofor, translated from the Romanian by Andreea Iulia Scridon, Naked Eye Publishing, 2021

Oh, what a sinister story, what bothersome spectres

my bedstead is creaking.

We will have to move in the night

to other rooms to other countries to other life-stories.

Spirituality, references to the Scriptures, and direct calls from God—Romanian poet Ion Cristofor is known as a “modern Christian poet,” but Somewhere a Blind Child exemplifies his idiosyncratic approach to faith. Drawn from nearly forty years of work, these selected poems are translated into English for the first time by Andreea Iulia Scridon, a translator and poet herself. They are spiritual, but also ridden by spirits; they frequently allude to the scriptures with reverence, but also do not refrain from ridiculing them at leisure—God calls in, but he himself “gets no erotic phonecalls.” Cristofor’s numbingly clear awareness around the contradictions of the modern world—in realms of religion, history, science, and death—keeps the reader from being lulled into any false sense of comfort, whether by confidence in faith’s power or excessive hope in reason. When earthly pleasures do barge in, however, their offer to distract from pain and worry is accepted with abandonment and sensual relish, no matter how ephemeral their soothing effect.

When she undresses on the couch

the blossom-laden trees all move into my bedroom

their love-sick leaves becoming delirious.

It’s autumn, Lord, it’s so late in heaven

and love is a blue orange in your hand

In this unusual meeting place between the chilly high planes of the spirit and the dirty warm ground of the senses, visions flourish. It feels oddly logical; wracked with doubt, a mind can become overattentive to extemporary signs—the shape of a cloud or the temperature in a room, taking them for premonitions or glimpses of the truth that lies behind the real, as they appear and disappear in the surreal and overheated atmosphere. The senses, if capable of guiding reason, can also distort it, making room for the incredible, the strange, and the eerie.

a white phantom passes through the rooms

reminding you of an hour of love

that once passed over you like a galloping herd of horses,

like a reckless ocean wave.

And now flocks of starlings proclaim you governor of the

province

and towards evening the clouds send you dark ambassadors.