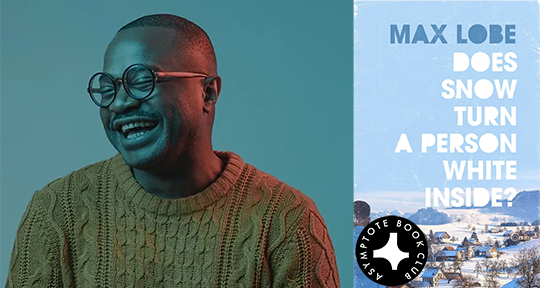

For our final Book Club selection of the year, Asymptote is proud to present a work emblematic of how writing can transform, subvert, and negate borders. In Does Snow Turn a Person White Inside?, Swiss author Max Lobe traces how the complex factors of race, class, sexuality, and migration can cohere in a single life, and how nationhood can be refracted and reinterpreted by those who refuse to be defined by the standard. Speaking in the extraordinarily vivid voice of his protagonist, Mwana, Lobe balances tragedy with joy, freedom with entrapment, and home with home.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

Does Snow Turn a Person White Inside? by Max Lobe, translated from the French by Ros Schwartz, Hope Road Publishing, 2022

As in love, mystery, and metamorphosis, the name of country draws a long throughline in our world of stories. Add to it a possessive—my country, your country—and the resulting narratives are instantly elaborated with the ontological intersections, demarcations, and dialogues that enmesh our landscape. Through this simple addition, a life is juxtaposed with a society, a single act comes to emblematise a culture, and an experience constitutes an identity—not necessarily out of any active political consciousness, but simply from having left, at some point, that arbitrary and mutable shape of one’s birthplace. Paul Gilroy, in conceptualising diaspora, described it as positing “important tensions between here and there, then and now, between seed in the bag, the packet or the pocket and seed in the ground, the fruit or the body.” To move across our jigsaw world is to know the fluid weight of difference and sameness—that they can be at once interchangeable and oppositional. These shifts from strangeness to familiarity do not begin with the boarding of a plane or a boat, but occur in minute swatches of conversation, in the passing from one minute to the next, between two people looking out at the same scene, not knowing what the other sees.

In Max Lobe’s Does Snow Turn a Person White Inside?, translated from the French by Ros Schwartz, country is introduced by the most immediate and intimate of desires—food. Our narrator, Mwana, is lugging “two huge sugar-cane bags” across Switzerland, with all the provisions and gifts of another nation inside: “Fumbwa, saka-saka, makayabu, okra and dried impwa.” The list goes on, rich with sugars and starches and svelte oils. Wrapped meticulously by his mother, the treasured packages have been carried by his sister Kosambela, across the continental divide from what Mwana calls Bantuland, to the nation where they both now reside: Switzerland of the Grütli Meadow and the Rütli Oath, of white-out peaks and lakeshore villas.

A recent graduate of the University of Geneva and a settled Swiss resident, Mwana is black, queer, and unemployed; it is this lattermost factor that rules his life, his daily preoccupations, and his physical and mental wanderings. With repeated trips to the unemployment office, small yellow coins dug out of household crevices, kindly deceptive calls to his mother—this scarcity is the precipice that Mwana dangles from, and as such it is the swinging, breakneck angle by which he interprets everything. The two bags he drags onto the bus from Lugano to Geneva contain emblems of home, of care, and of a beautiful eradication of distance, but most importantly, they are an antidote to hunger. Amidst Lobe’s warm, loquacious prose, we first see the dissipation of difference into sameness, the shift from displacement in country to immediacy in the body. In all the discursive paths the mind takes to arrive at a single place, we see the need to live. READ MORE…