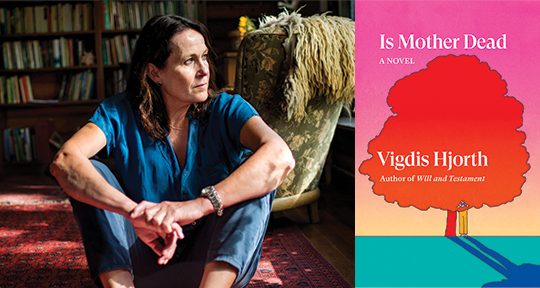

Is Mother Dead by Vigdis Hjorth, translated from the Norwegian by Charlotte Barslund, Verso Books, 2022

In a charming 2017 interview with the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark, Norwegian writer Vigdis Hjorth sang the praises of Kierkegaard, quoting the proto-existentialist on life being a task and an adventure—the adventure just to be you, “every single day with great fervor and responsibility.” Her novels, over a dozen of them, instantiate this charge, with several following characters grappling with existential crises precipitated by a sense of alienation from their families, their past, and their own authentic selves.

Such a crisis breathes life into her latest novel, Is Mother Dead, out with Verso Books and translated by Charlotte Barslund. Joanna is the narrator and protagonist, a successful artist in her mid-sixties who is estranged from her family, which inevitably causes an estrangement from her past and—she wonders—her true self. Confronting her family—her mum and the woman’s role in affecting the formation of Joanna’s self in particular—becomes the task of Joanna’s art and her life, this adventure driving the novel.

What could cause a rift in a family so enduring that decades later, a daughter is forced to stake out her mum’s apartment just to confirm she isn’t dead? Writing with a rush of anxious interiority beautifully reproduced by Barslund’s translation, Hjorth spins out Joanna’s hopes, fears, and half-suppressed memories in obsessive and propulsive run-on sentences, full of self-reflexive questions and crushing doubt. Though Joanna’s “default setting” is feeling alone in the world, she is compelled to confront her mum to understand something deeper about herself—to consult her deepest self, because “. . . we all carry our mothers like a hole in our souls.” Her mum has no interest in such confrontations or consultations, and therein lies the conflict.