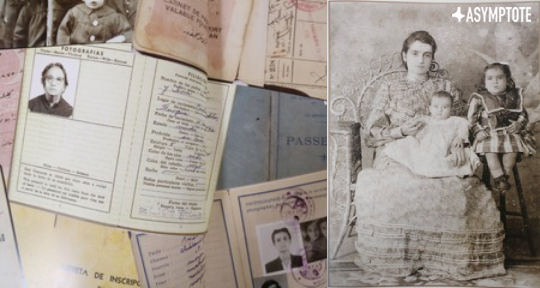

Canan Maraşlıgil’s world has always been a multilingual one. Currently based in Amsterdam, she was born in Turkey, spent her childhood in Belgium, and, as a student, lived for a short time in Canada. Today, as a freelance writer and literary translator, she often travels internationally to deliver workshops and presentations, and works in no less than five languages: English, French, Turkish, Dutch, and Spanish. Always involved in several inspiring projects at once, Canan explores literature through writing and translation, but also photography, video, podcast, and digital media. You can therefore easily imagine our joy when, in addition to all of her brilliant projects, she kindly agreed to schedule an interview with Asymptote’s team member Lou Sarabadzic.

Lou Sarabadzic (LS): You work mostly in French, English, and Turkish, and are regularly involved in projects dealing with multilingualism. What does multilingualism mean for you, and why is it so central to your work?

Canan Maraşlıgil (CM): Multilingualism is my reality. I grew up in a family who came from Turkey to Belgium. We spoke Turkish at home, I went to school in French, then I learned Dutch at school (Belgium is a trilingual country if you count German, but the second language we learned at school was Dutch). I was also hearing a lot of German in our living-room through TV and our cousins living in Zurich and Hamburg—I also have family who migrated to Germany. I started to learn English through friends of my dad who was working in a hotel as a night receptionist, and through popular culture—films and music. However, English only became part of my formal education much later. Now, I start my sentences in one language and end them in another. In my mind, everything is multilingual. Certain feelings come to me in one language, and others in another language. I also work in Dutch a lot, but I don’t really feel in Dutch, nor in Spanish, which is also a language I know, but use much less.

Multilingualism means seeing the world through many different lenses. You can try and understand issues and current affairs through different media in different languages. I think that’s a huge advantage in today’s world.

READ MORE…