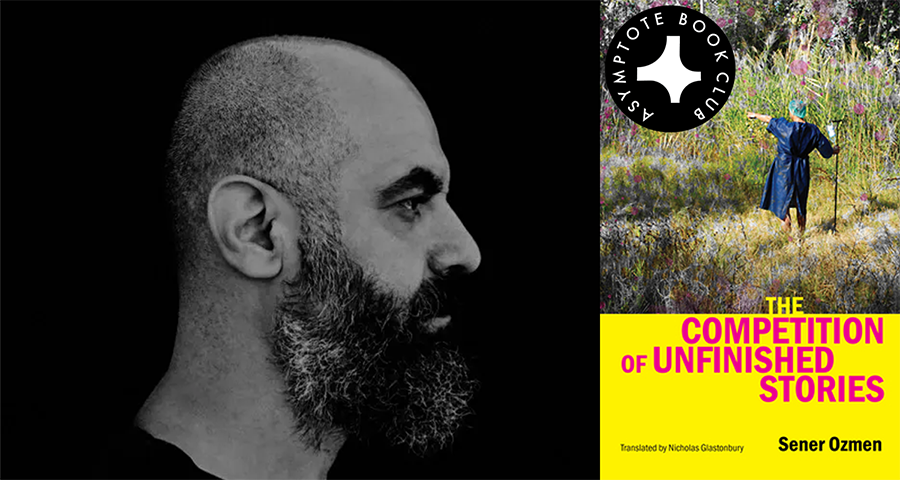

The Competition of Unfinished Stories is one of those texts that would be classified as “untranslatable” by the more cynical amongst us. Aside from addressing the intricate language politics of Turkey—namely the oppression and marginalization of Kurdish—Sener Ozmen’s text is full of jokes, narrative tangles, loose ends, shapeshifting characters, and suspicious translators. As such, the English edition of the novel is a triumph, not only in Nicholas Glastonbury’s fluid and adventurous prose, but also in his own interjections that celebrate the original’s chaos and multiplicity. In this interview, he speaks on the challenges of translating the book, authorial authority, and language’s resistance to containment.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

Hilary Ilkay (HI): This is a challenging and strange book! How did you find out about it? Did you pitch it to a publisher, or was it pitched to you?

Nicholas Glastonbury (NG): I met Sener maybe six years ago. I was in Diyarbakır doing research for my PhD, and there was an organization trying to build an online platform for Kurdish literature, given all of the obstacles that it has in accessing foreign language audiences, and I did some work for them. I was aware of Sener’s work a little bit, but when I met him, I became really interested in it. He’s also a visual artist, so I became really interested in how he saw the world. He’s also written quite a few books; The Competition of Unfinished Stories is his second novel, and the title is what drew me in. After I read it, I thought, what is going on here? This is a crazy book. Then I began pitching it around, and it landed with Sandorf Passage, which I’m very happy about.

HI: I was delighted to discover Sener’s prolific artistic practice when I was reviewing the book. I wonder if you could say a little bit about how you see his practice as a visual artist influencing his writing. Do you see an interplay between his art and the way that he constructs stories and narratives?

NG: I think he’s really interested in the absurd. For example, there’s one photograph of his that comes to mind; it’s a group of men hoisting a flag up a flagpole, and they’re all wearing neck braces, and they’re unable to look up at the flag. There’s a tension between violence and nation, and the obligation to nation is very much an aspect of this novel.

He has another piece, a sequence of photographs of himself dressed as Superman. He takes off his cape and uses it as a prayer rug, and the title of the work is “Supermuslim.” He’s got a real sense of humor about things that are so heavy and serious.

There was another piece he did called “Road to Tate Modern,” which is him and another artist trying to make their way to London, to the museum. They do a kind of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza act, riding a horse and a donkey, asking shepherds around the Kurdish countryside where the Tate Modern is. And the shepherds say things like, oh, it’s just over the hill. . . So there’s a sense of the distance that Kurdish cultural production has to surmount in order to reach international audiences—of course conditioned by the violences of the nation-state—that comes through in both his writing and his visual work. I think the way that his approach to writing is shaped by his visual work is how he captures images. For example, in The Competition of Unfinished Stories, the image of Neil Armstrong on the prayer mat dying stands out to me, or all the scenes of Sertac masturbating. There’s a real sense of creating these absurd tableaus, and I think that’s probably influenced by how he sees and visualizes the world through his art.

HI: You have such an impressive and interesting portfolio of translations under your belt and I’m curious, given the scope of your work, what made Ozmen’s writing unique, or what stood out about the way that he wrote? And related to that, what was the biggest challenge in trying to render this unwieldy text into English? READ MORE…

Blog Editors’ Highlights: Winter 2025

Reviewing the manifold interpretations and curiosities in our Winter 2025 issue.

In a new issue spanning thirty-two countries and twenty languages, the array of literary offers include textual experiments, ever-novel takes on the craft of translation, and profound works that relate to the present moment in both necessary and unexpected ways. Here, our blog editors point to the works that most moved them.

Introducing his translation of Franz Kafka’s The Trial in 2012, Breon Mitchell remarked that with every generation, there seems to be a need for a new translation of so-called classic works of literature. His iteration was radically adherent to the original manuscript of The Trial, which was diligently kept under lock and key until the mid-fifties; by then, it was discovered exactly to what extent Max Brod had rewritten and restructured the original looseleaf pages of Kafka’s original draft. It is clear from Mitchell’s note that he considers this edit, if not an offense to Kafka, an offense to the reader who has lost the opportunity to enact their own radical interpretation of the work: an interpretation that touched Mitchell so deeply, he then endeavored to recreate it for others.

In Asymptote’s Winter 2025 Issue, the (digital) pages are an array of surprising turns of phrase and intriguing structures—of literature that challenges what we believe to be literature, translations that challenge what we believe to be originality, and essays that challenge what we believe to be logic. I am always drawn to the latter: to criticism, and writing about writers. As such, this issue has been a treat.

With the hundredth anniversary of Kafka’s death just in the rearview and the hundredth anniversary of the publication of The Trial looming ever closer, the writer-turned-adjective has not escaped the interest of Asymptote contributors. Italian writer Giorgio Fontana, in Howard Curtis’s tight translation, holds a love for Kafka much like Breon Mitchell. In an excerpt from his book Kafka: A World of Truth, Fontana discusses how we, as readers, repossess the works of Kafka, molding them into something more simplistic or abstract than they are. In a convincing argument, he writes: “The defining characteristic of genius is . . . the possession of a secret that the poet has no ability to express.” READ MORE…

Contributors:- Bella Creel

, - Meghan Racklin

, - Xiao Yue Shan

; Languages: - French

, - German

, - Italian

, - Macedonian

, - Spanish

; Places: - Chile

, - France

, - Italy

, - Macedonia

, - Switzerland

, - Taiwan

, - Turkey

; Writers: - Agustín Fernández Mallo

, - Damion Searls

, - Elsa Gribinski

, - Giorgio Fontana

, - Lidija Dimkovska

, - Sedef Ecer

; Tags: - dystopian thinking

, - identity

, - interpretation

, - nationality

, - painting

, - political commentary

, - revolution

, - the Cypriot Question

, - the Macedonian Question

, - translation

, - visual art

, - Winter 2025 issue

, - world literature