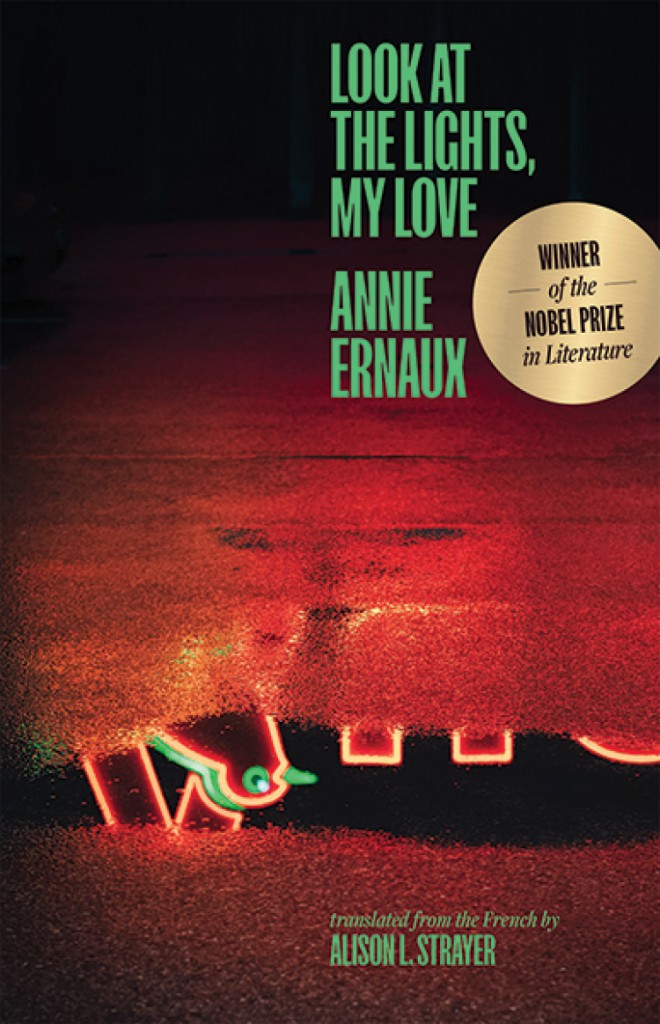

This Translation Tuesday, we are pleased to present new short fiction from the Montenegrin author Tijana Rakočević. A surprise awaits—for this story takes place not in contemporary Montenegro, as one might expect from the author’s identity, but in Tanzania’s colonial past, during the Kashasha laughter epidemic of 1962. This hypnotic tale describes the outbreak of the epidemic in remote Tanzania following the arrival of a British agent. As the narrator returns continually to the central image of a vitiligo-mottled fawn, whose coloration is mirrored by that of the disabled protagonist, Andwele, a haunting parable of illness, dehumanization, and assimilation emerges, rendered here in elliptical but powerful English by Will Firth.

Wache waseme nimpendae simwachi.[1]

If you never leave the house, no tragedy can befall you.

The edges of Tulinagwe’s purple khanga danced in the air as she kneaded a ball of risen dough. Whenever eight-year-old Andwele, as piebald as a scrofulous calf, stuck his finger into his mouth so far that he could touch the back of his throat, she would snarl, You sure know how to get on one’s nerves, boy, but this time she held her tongue. He tested her patience by rocking on a loose wooden board on the ground that moved to the rhythm of his round heels, and he only stopped when his mother glanced at him; in those moments, he felt I’m the center of the world, but she—if she had the strength to speak—would have called it asking for a hiding. It was a holiday in all Kashasha: the white man, Sir Jonathan, had returned—a dissolute English bon vivant, who their Baba wa Taifa, their savior Mwalimu, Julius Kambarage Nyrere, had befriended in Edinburgh during his studies. Tulinagwe saw him out of the corner of her eye as he ambled along the main road escorted by a gaggle of black girls, and, if she had not been busy rolling the dough for the family, which was so thin that it kept breaking in the middle, she would have said, not particularly handsome, not particularly tall; instead, she decided, I’ll save salt; if they still like it, they can ask for more.

Andwele slipped and fell. It was a tragedy.

He remembered that Mwanawa had given him five shillings and he limped off through the yard. The women wanted him to leave the village, which he sensed in the way they prepared him for the trip and because they had whispered ever since Kyalamboka lived in Sir Jonathan’s house. The man’s collection of romantic safari oddments in his private residence—photographs with animals, human animals, and human humans—seemed a grotesque combination to him, who imagined Muleba district as a mind-bogglingly vast Tanzanian shilling: go banana picking, they would have advised him if he were older, I’ll go cotton picking like Ipyana, my dad, he thought, but he lacked the courage. After that unusual visit, he believed Muleba was a heart broken. Hidden in the bushes near the house, he tried to get a glimpse of the vitiligo fawn that bwana had brought as a trophy from Europe, a fawn they called Sekelaga, Joy, but it was not there; he just heard the titillated giggles of his elder sister that vanished in the warm breeze. What did he promise her, he wondered, and will he take her with him? He would notice a villager and hire them to scrub the floors, and he would look on that troglodyte as human—that was the fortunate circumstance that made them dignified in their own eyes. The foreigner, always well-meaning and amicable, as if his earthly life depended on that handful of semi-savages, offered him Abba-Zaba chocolates so he would keep the secret; Andwele first spoke hapana, hapana, later nasikitika, but he was captivated by the sweet pain in his throat: asante sana, he repeated more and more often, thank you very much. He went away calm and beaming, his face radiant like a young idiot, dragging along his leg that they broke four more times after the accident, only to conclude it was better to leave it. Kyalamboka watched her disfigured brother and snorted spitefully in her rich lover’s ear, that little freak—sometimes I’d like to trip him up.