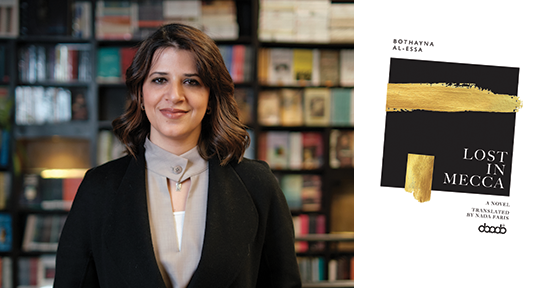

Lost in Mecca by Bothayna Al-Essa, translated from the Arabic by Nada Faris, Dar Arab, 2024

Best-selling Kuwaiti author Bothayna al-Essa’s Lost in Mecca —first published in Arabic in 2015 as Maps of Wandering/خرائط التيه—is more than just a literary crime thriller; it’s a journey through Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt, as well as into the minds of its protagonists. Al-Essa moves from a mere personal incident to a human plight and the global crisis that is human organ trafficking, resulting in an expansive narrative and a much welcome addition to the growing list of modern Arabic fiction available in English.

Lost in Mecca opens with the ordeal of a couple on Haj. As a flood of pilgrims circumambulate the Kaaba, al-Essa focuses on a Kuwaiti woman, Sumaya, holding the hand of her seven-year-old son, Mishari—who she has brought along even though it’s not obligatory for children to participate in this annual journey. Sumaya’s husband, Faisal, is also performing the same ritual nearby. All of a sudden, a group of Africans rushes forward, holding onto each other, and in the chaos, Mishari’s hand slips away from Sumaya’s. In this human flood, Mishari is lost.

The spiritual scene soon fades away, and the flooded square transforms into an empty place filled with the echoing cries of a grieving mother, repeating, “Mishari! Oh God! My son!”, over and over again. The bodies diminish, the crowd thins, the distances shorten, the gaps decrease, and Mecca itself becomes a maze. How could a child possibly vanish in all this confusion?

From that point onward, the tragedy truly begins with the search for Mishari, a pursuit that transcends the boundaries of pages to become a terrifying nightmare. The ensuing chapters chronicle Mishari’s wanderings between the 7th and 29th of Dhu al-Hijjah, continually being confronted by the ‘forgotten’ worlds and stories of human negligence taking place across the Middle East. Al-Essa stretches out his challenging storyline from Mecca to ‘Asir, Jazan, and the Red Sea coast. Eventually, Mishari’s parents will even cross the sea towards Sinai through restricted maritime routes. The narration covers the Sinai desert and its vast expanses, up to the borders of Al-‘Arish in the north. It also highlights the geographical boundaries of occupied Palestine, and sheds light on what the Western media has reported regarding human organ trafficking, and secret deals involving Israeli and Egyptian officials.