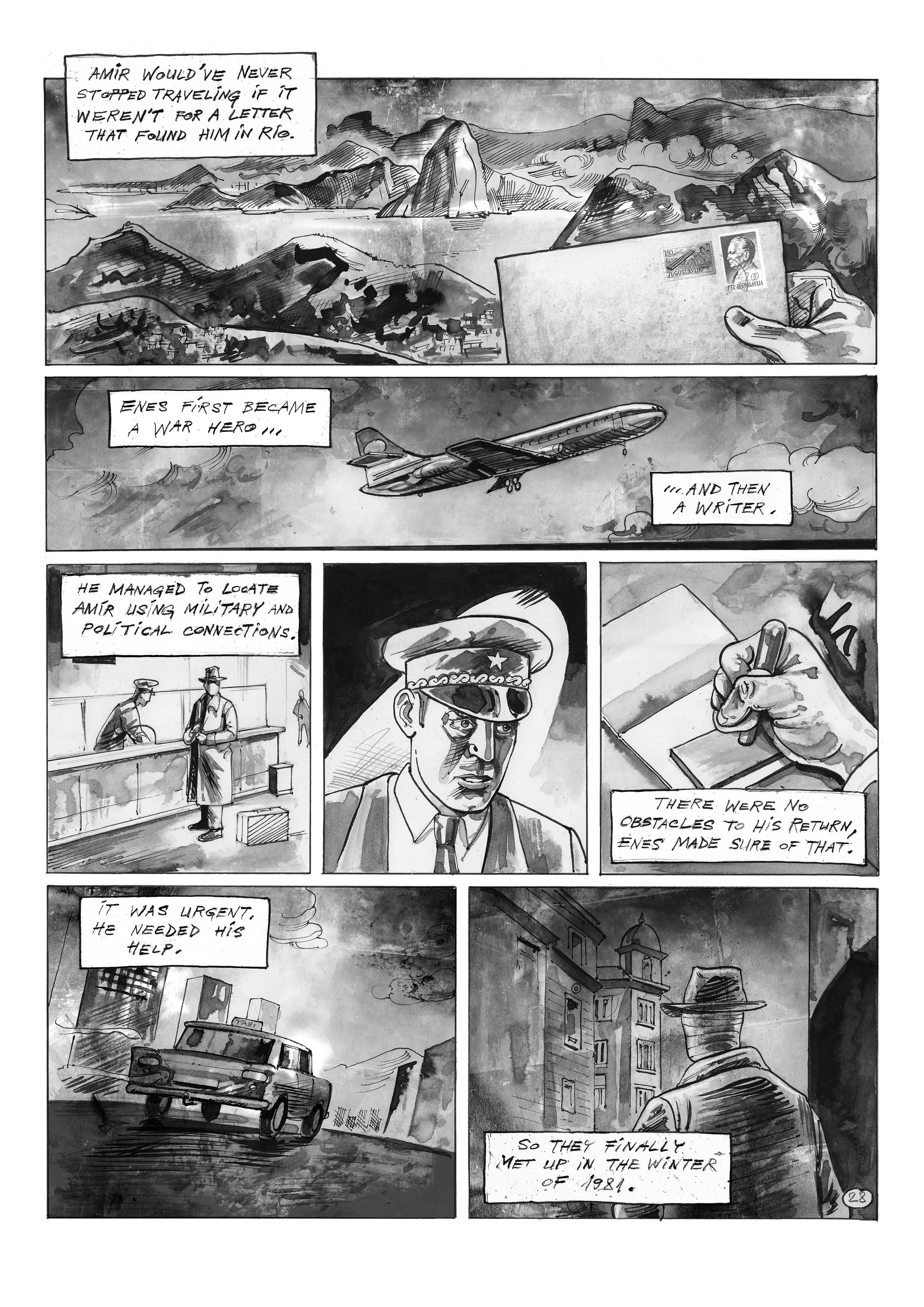

Igor Štiks is no stranger to Asymptote. As his April 2012 interview with us states, he was born in Bosnia, wrote his books in Croatia, and now divides his time between Edinburgh and Belgrade. The title character of Štiks’ soon-to-be-published novel, The Judgement of Richard Richter, is a Viennese writer and journalist who retreats from Paris and a painful divorce to his childhood home of Vienna just as he’s turning fifty, in 1992. In the midst of remodeling the apartment where he’d been raised by his aunt Ingrid, he stumbles on a letter written by his late mother, hidden in a blue notebook, tucked behind a bookcase in a wall he’d been demolishing.

From the unsent letter, he learns that his father was a man Richard had never heard of—someone called Jakob Schneider, a leftist Jewish antiwar activist from Sarajevo. Just then, in April of 1992, the war is breaking out in Bosnia. Moved by this unexpected information about his parentage and the mounting hostilities in Bosnia, Richter decides to go to Sarajevo to report from there as a war correspondent and, while he’s there, to search for more information about his father.

Once he arrives he is quickly caught up in the reality of the war and, at first, he sets aside his search for his father. Instead he finds a student, Ivor, to serve as his guide and translator, and he and Ivor decide to shoot a film about a play which is being rehearsed, amid the terrifying conditions of the siege, by a Sarajevo theater, based on a script adapted from the novel, Homo Faber, by Max Frisch. While working on the play he falls in love with Alma, the play’s leading actress. It is from this love affair and the outcome of the search for his father that he flees with such shame and horror, as described in the opening sentences of the excerpt, which we’re thrilled to present to you today in contributing editor Ellen Elias-Bursac’s excellent translation.

When the United Nations transport aircraft took off from Sarajevo on the morning of July 7, I was convinced that shame would strike me dead right there if I looked back once more at the city. I stayed in the seat I’d been assigned and fended off the desire to gaze one last time through the window at Sarajevo as I fled. I held my face in my hands, dropped my head to my knees, and didn’t even rise to lift a hand and wave to the besieged city I’d arrived in as a journalist in mid-May—only to desert it that day like a coward running from my own personal catastrophe, which had intertwined so strangely with the city’s calamity. Coward-like, I repeat, with no word of farewell. Or better, like a beggar in disguise, because there was nothing left of the old Richard Richter but, perhaps, the name on the accreditation ID that allowed him to board the aircraft as simply and painlessly as if hailing a cab to whisk him away from a war he had no tie to whatsoever.

And the tears that dripped onto the grimy iron deck of the aircraft, finding their way through his tightly squeezed fingers, might be perceived as nothing more than a perfectly reasonable human response to what he’d been through, a reaction to the stress that is invariably a part of the work of a journalist, a release of emotions now that the danger had finally passed, after our famous writer, valiant correspondent, and shrewd analyst of this tragic European war at the century’s end had chosen to withdraw. Perhaps to write a fat new book about his experiences and the bravery it took to be there, on the spot, before anybody else could, to open the eyes of Europe—as long as the honorarium was generous enough. No one knew that the man they took pains to extract from the plane that hot day in Split when the plane had landed was no longer the man listed on the ID attached to his shirt. No longer did he answer to that name.

READ MORE…