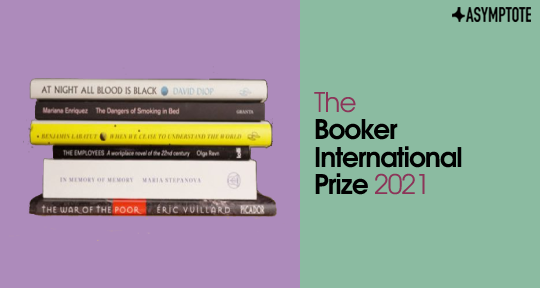

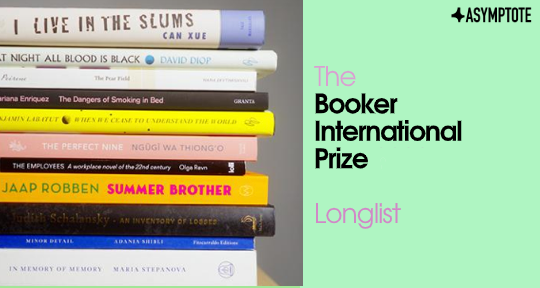

With the announcement of the Booker International 2021 winner around the corner and the shortlisted titles soon to top stacks of books to-be-read around the world, most of us are harboring an energetic curiosity as to the next work that will earn the notoriety and intrigue that such accolades bring. No matter one’s personal feelings around these awards, it’s difficult to deny that the dialogue around them often reveal something pertinent about our times, as well as the role of literature in them. In the following essay, Barbara Halla, our assistant editor and in-house Booker expert, reviews the texts on the shortlist and offers her prediction as to the next book to claim the title.

If there is such a thing as untranslatability, then the title of Adriana Cavarero’s Tu Che Mi Guardi, Tu Che Mi Racconti would be it. Paul A. Kottman has rendered it into Relating Narratives: Storytelling and Selfhood, a title accurate to its content, typical of academic texts published in English, but lacking the magic of the original. Italian scholar Alessia Ricciardi, however, has provided a more faithful rendition of: “You who look at me, you who tell my story.” This title is not merely a nod, but a full-on embrace of Caverero’s theory of the “narratable self.”

Repudiating the idea of autobiography as the expression of a single, independent will, Caverero—who was active in the Italian feminist and leftist scene in the 1970s—was much more interested in the way external relationships overwhelmingly influence our conception of ourselves and our identities. Her theory of narration is about democratizing the action of creation and self-understanding, demonstrating the reliance we have on the mirroring effects of other people, as well as how collaboration can result in a much fuller conception of the self. But I also think that there is another layer to the interplay between seeing and narrating, insofar as the act of seeing another involves in itself a narrative creation of sorts; every person is but a amalgam of the available fragments we have of them, and we make sense of their place in our lives through storytelling, just as we make sense of our own.

I have started this International Booker prediction with Cavarero because I have found that this year’s shortlist—nay, the entire longlist—is explicitly focused with questions of archives, loss, and narration: what is behind the impulse to write, especially about others, and those we have loved, but lost? Who gets to tell our stories? It is a shame that Adania Shibli’s Minor Detail, translated by Elisabeth Jaquette—as one of the most interesting interjections on the narrative impulse—was cut after being first longlisted in March. The second portion of Minor Detail sees its Palestinian narrator becoming obsessed to the point of endangerment to discover the story that Shibli narrates in the first portion of the book: the rape and murder of a Bedouin girl, whose tragic fate coincides with the narrator’s birthday. This latter section of the book is compulsively driven by this “minor detail,” but there is no “logical explication” for what drives this obsession beyond the existence of the coincidence in itself. READ MORE…