Looks like 2026 isn’t coming in slow. Despite the chaos, we’re looking forward to another year of illuminating the best of what world literature has to share—and we’re starting off with plenty to go around, with thirteen titles from ten countries. Find in the mix a new translation of one of the Peruvian canon’s most dazzling and convulsive works; a novel depicting the delicate indigenous customs of a region between Siberia and northeast China; a shocking, propulsive novella from a Japanese cult writer; a story of transformative grief from an enthralling Romanian voice, and so much more.

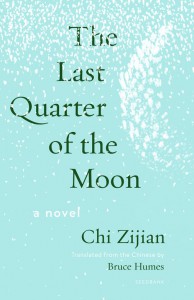

The Last Quarter of the Moon by Chi Zijian, translated from the Chinese by Bruce Humes, Milkweed Editions, 2026

Review by Mandy-Suzanne Wong

The opening lines of Chi Zijian’s wondrous novel, The Last Quarter of the Moon, set a carefully measured tone for this enchanted story of Evenki nomads: “A long-time confidante of the rain and snow, I am ninety years old. The rain and snow have weathered me, and I too have weathered them.” this rich and essential passage gently, and with deference, opens a window into a world where humans confide in rain. Chi and translator Bruce Humes indulge the word weather in at least three of its meanings, conveying the narrator’s resilience and hinting at her costly intimacy with other-than-human energies.

A word exchanging its meaning for other meanings—as if adopting different bodies to slide between existential contexts—invokes the dynamism of the shamanic Evenki cosmos, wherein earth and sky, humans and nonhumans, the embodied and the disembodied, dance together in precarious balance and tender reciprocity. Everything is alive in the Evenki’s animist multiverse, every entity ensouled, each Earthling an embodiment of the Spirits, and every human owes a debt to the Spirits for the lives of nonhumans killed for food. In turn, when a human child goes missing, in danger of freezing to death, a reindeer child must go “to the dark realm on [the human’s] behalf,” in a mimetic exchange.