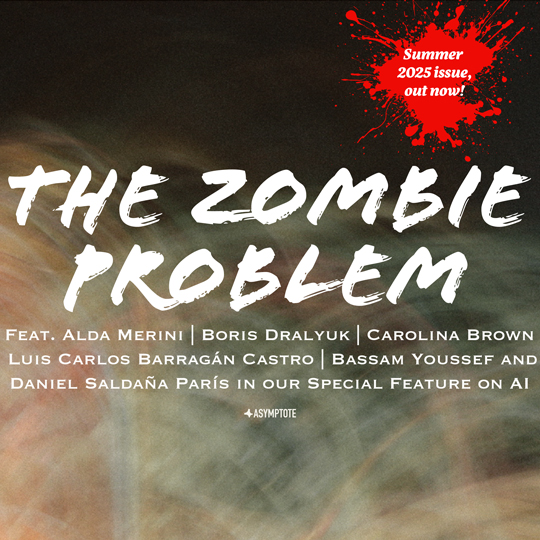

Do other people have inner lives? Or are they just NPCs with no consciousness, no soul? We can’t know for sure! Philosophers call this “the zombie problem,” which also happens to be the tagline of our Summer 2025 issue. Not least because there is an actual zombie featured for the first time in our pages via Carolina Brown’s biting cli-fi; the “zombie problem” is also at the heart of any discussion about AI—the theme of this edition’s wildcard Special Feature. Alongside MARGENTO’s extraordinary hybrid human-AI work, we are proud to bring you an exclusive interview with acclaimed translator Boris Dralyuk, a dossier of poems by the beloved Italian master Alda Merini, an excerpt from Lithuanian novelist Valentinas Klimašauskas’s genre-bending Polygon, a pair of pieces by Anna Tsouhlarakis and Syaman Rapongan centering their indigenous worldviews, and our first article from the Azerbaijani amid new work from 32 countries—all of it movingly illustrated by Singapore-based guest artist Xin Lui Ng.

The question of consciousness takes center stage in our Special Feature on AI—not the ersatz sentience of AI itself, but rather the uneasy cognizance, among members of the literary community, of its disruptive potential this side of singularity—hence the Feature’s title, “What AI Can’t Do.” From Daniel Saldaña París’s incisive meditation on AI in translation to S. K. Birk’s tale of a fiction-generating chatbot forced into the role of a lonely girl’s eternal yes-man, these pieces highlight the limits of AI as a tool for transforming the more fundamental problems of a society that too often turns a blind eye to hegemony and suffering.

Elsewhere, “the zombie problem” becomes grotesquely literal, from the undead trudging across post-climate change Antarctica in Brown’s “Anthropocene” to the humanoid fungi encountered by the hikikomori in Luis Carlos Barragán Castro’s intense mind trip of a story “Cephalomorphs.” One might turn into a zombie too, carrying out inhuman orders on behalf of an authoritarian regime as we see in Syrian writer Bassam Yousuf’s devastating real-life account of a childhood friend-turned-torturer. Even in more idyllic circumstances, one can suddenly discover that one is “no longer there,” that one has become “a suspended, emptied image, merged with its surroundings,” as Slovenian poet Jana Putrle Srdić puts it in “End Of The World, Beginning”; indeed, social norms can disfigure a person until they lead a life that is more performance than living. In Drama, Yannis Palavos gives us the story of a man dogged by crime and a daughter dogged in turn by his memory, her searching monologue part exorcism, part attempt to restore humanity to them both. Appearing in English for the very first time in our fourth Special Feature themed on outsiders, Bolivian author Rodrigo Urquiola Flores’s encounters with Venezuelan refugees unfold across a gamut of misadventures—but through it all he never lets us forget their humanity or his.

In light of the recent flurry of announcements surrounding AI-powered literary translation services, this seems as good a moment as any to gently remind our readers that Asymptote has, for the past fifteen years, been a painstakingly human endeavor. Nothing about our work—from the meticulous curation of each issue to the minutiae of holding together a far-flung, 100-strong virtual team—has ever been generated by machine or delivered at algorithmic speed. If the growing encroachment of AI into daily life has deepened your appreciation for human creativity and labor, we warmly invite you to support us by becoming a sustaining or masthead member. Long live human-powered literature!