Imagine translating a book based on your own life… That’s exactly what Priscilla Layne did with Birgit Weyhe’s German graphic novel Rude Girl, published in English by V&Q Books.

Faced with accusations of cultural appropriation for her comics depicting Black characters’ stories, Weyhe was looking for a new approach when she met Priscilla Layne. A Chapel Hill professor of German and African Diaspora Studies, Layne grew up in Chicago with Bajan and Jamaican parents and learned German after watching Indiana Jones as a child – that’s what she’d need to fight Nazis, after all. Later, a fascination with Kafka and May Ayim fueled that enthusiasm even more.

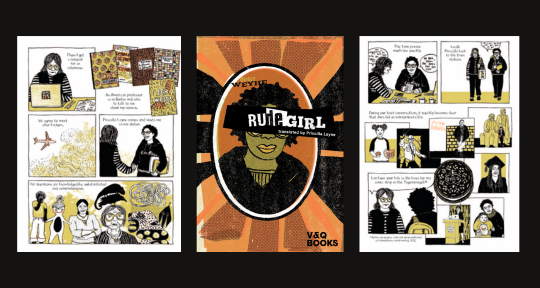

This time around, the author and her subject collaborated closely. First Priscilla told her life story, then Birgit drew a chapter and sent it to her. Priscilla gave feedback – “not using skin color in the drawings implies a ‘post-racial’ society; I prefer it when you combine two colors, like in your earlier comics,” for instance – and Birgit picked that up and adapted the way she worked as she went along. Each chapter is followed by a separate section detailing Priscilla’s comments and explanations.

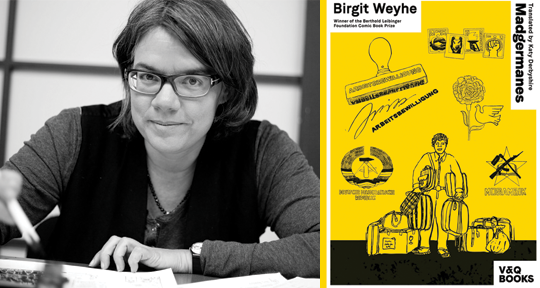

The book came out in German in 2022 and was promptly shortlisted for the prestigious Leipzig Book Fair Prize – the first graphic novel ever to be nominated. Berlin-based imprint V&Q Books had previously published Birgit Weyhe’s Madgermanes, a comic about Mozambican contract workers in the GDR. And publisher Katy Derbyshire not only shares Priscilla Layne’s love of German literature… they’re also both big fans of punk, ska and reggae. In fact, their paths presumably crossed at gigs in Berlin during Priscilla’s time as an exchange student there. It’s the rude girl culture of the title that provided her with a sense of community among anti-racist skinheads, and the book features great stylized drawings of album covers that shaped her life at various stages – something Derbyshire very much related to.

So it was a no-brainer to publish Rude Girl in English, and it was clear who’d have to translate it. Priscilla Layne had previously worked on writing by Feridun Zaimoglu and Olivia Wenzel, but Rude Girl posed new challenges. As she writes in her translator’s note, “having your life displayed on the page requires a degree of vulnerability.” The graphic novel explores personal and political hurdles she has faced and doesn’t shy away from depictions of difficult experiences, though they’re not always literal; Birgit Weyhe has a special gift for apt metaphors in illustration form.

In the end, the book is a beacon for a great many readers. As Priscilla Layne writes: “If you are a Black nerd, any other nerd of Color, or even just a femme-identifying nerd, you don’t necessarily see any (positive) representation of yourself. I’m glad Rude Girl is helping to contribute to these representations and that it is now available in English.”

Find out more about Rude Girl here.

This is a sponsored post.