This week, our editors-at-large take us to India, Kenya, and México. From a cross-cultural poetry retreat to a crime writer’s conference, read on to find out more!

Réne Esaú Sánchez, Editor-at-Large, reporting from México

Not so long ago, I was talking with some friends about the Guadalajara International Book Fair and how, for many locals, an event like that was actually their only chance to find certain books, meet certain authors and even reflect upon their literary activities. Despite the importance of the Fair, literary circulation remains centralized in Mexico City, while book commercialization in other places like Guadalajara, Monterrey, or Oaxaca is always secondary.

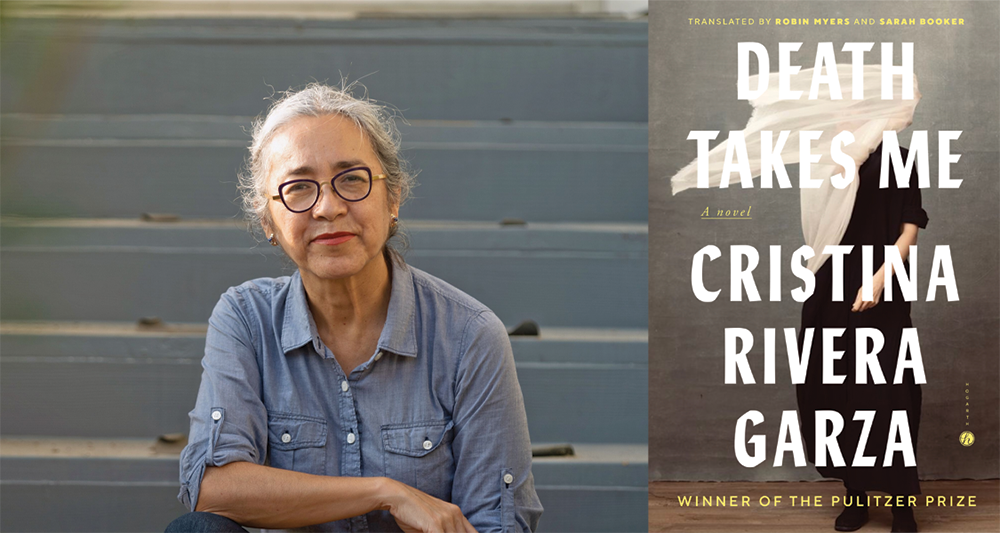

This is why I find it important to celebrate events like the Yucatán International Reading Fair (FILEY), which will conclude this Sunday, March 30. This year, it has hosted important authors including Cristina Rivera Garza, Verónica Murguía, Brenda Lozano, Jorge Comensal, and Xita Rubert. At the Fair, the 2025 José Emilio Pacheco Award for Excellence in Literature was presented to Alberto Ruy Sánchez, a prolific novelist who, in his unique style, shared the reasons behind his writing:

I write to know, to explore vast dimensions of reality that only literature can penetrate. I also write to remember, but no less, I write to forget. I write to extend my body, my senses, to experience the sensuality of the world day after day. I write for pleasure, for desire, for rage. To expose the falsification of icons, the abuse of public power. I write to be hated and to be loved, more so, to be desired. I write to propose new spaces in this world, to create places.

As its name suggests, FILEY has also been a space to reflect on why, how, and from where we read, something essential if we want to address the problem of cultural centralization. As María Teresa Mézquita, the Fair’s director, said in her opening remarks at the festival, beyond numbers and sales, the event is driven by a desire to foster personal growth, learning, and a cultural environment enriched precisely through reading.

It is good, as Ruy Sánchez’s remarks suggest, to know why we write; just as important is knowing why we read.

Wambua Muindi, Editor-at-Large reporting from Kenya READ MORE…