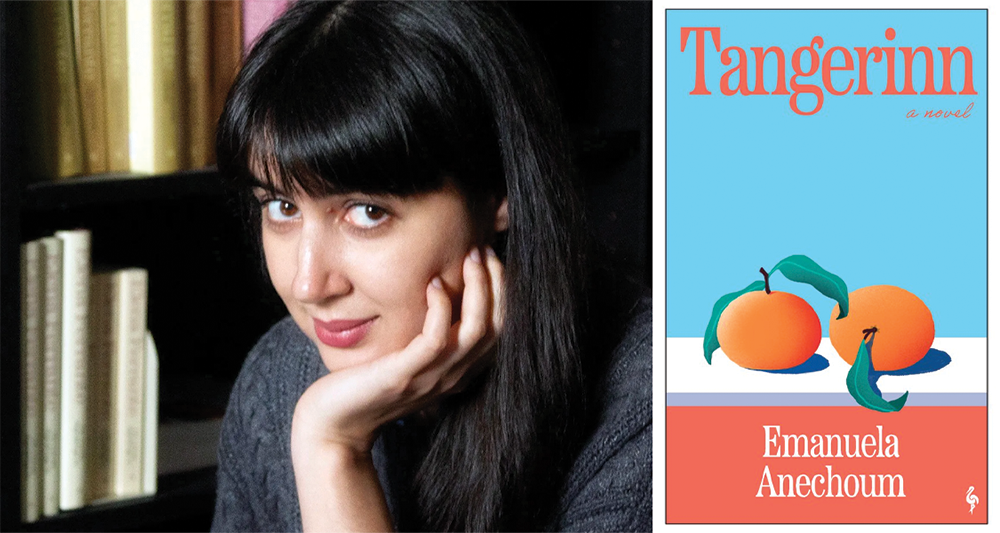

Tangerinn by Emanuela Anechoum, translated from the Italian by Lucy Rand, Europa Editions, 2026

When Mina, the first-person narrator of Emanuela Anechoum’s debut novel Tangerinn, returns to her childhood home in southern Italy after the death of her father, she is argumentative and defensive. She fights with her sister Aisha who picks her up at the airport—about hair removal, head scarves, who knew their father best. Though some of this prickliness could be due to grief, her pre-loss self has already been established as someone quick to judge, who has shored up a levee of self-defense. Mina readily admits to herself that she is a knot of “inadequacy and fear” and is most on edge trying to answer the question of who she really is. Though this query is always loaded, it is particularly so in this novel that takes on the weighty contemporary topics of cross-generational immigration and the social digital landscape.

The beginning of Tangerinn takes place in London and shares resonances with Vicenzo Latronico’s Perfection, published in English earlier this year. Like Mina, Latronico’s couple have moved from Italy to northern Europe and define themselves by their curations—what brands, plants, colors, furniture, and neighborhood they live in. But while the insecurities of Perfection remain mostly placid below this veneer, Mina dislikes her acquiescence to this powerful, social dictate, which is represented by her roommate/mentor/idol Liz. Before Mina receives the call about her dad’s death, she and Liz are having a conversation about envy, at which Mina thinks: “I envy everyone, all the time. I constantly envy people who are beautiful, rich, happy, sure of themselves. I’m full of venom for other people’s privilege, and I also envy their merits. I hope Liz loses everything she has.” Yet Mina must have Liz as her friend, because only Liz—the influencer who has everything—can be the reassurance that she is getting her life in London right. READ MORE…