Place: Iran

Asymptote Podcast: Favorite Readings of 2017

Start out 2018 right by taking a listen to our favorite readings published over the last year.

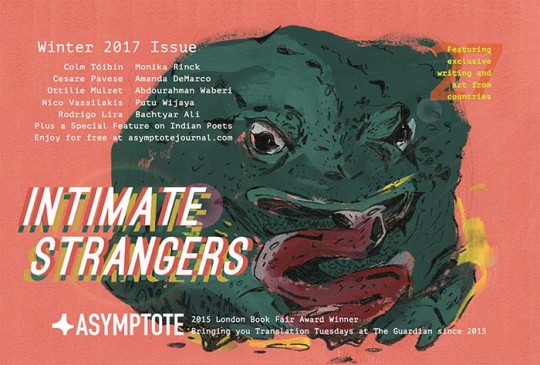

What an overwhelming ten days since the launch of the Asymptote Book Club! We received queries from as far afield as Australia and Canada—so much interest from Canada, in fact, that we decided to open our book club to Canadians four days ago. But why a book club in the first place? some asked. Well, in a nutshell: the idea was to take the important work we have done with our award-winning, free online journal and our Translation Tuesday showcases at the Guardian—that is to say, showcasing the best new writing from around the world, and giving it a physical presence outside of the virtual arena. We also wanted to celebrate (as well as support) the independent publishers who work hard behind the scenes to make world literature possible.

What sets your book club apart from others?

Curation is a big part of what makes the book club special. We have a large team of editors based in six continents to research and pick the best titles available from a wide variety of publishers. Subscribers will receive a brand-new (just published or, in many cases, not even in the bookshops yet), surprise work of fiction delivered to their door each month. This is another thing that distinguishes us from a few other book clubs before us: we choose from new releases only—nothing from a backlist that readers may already have on their bookshelves.

Subscriptions are for three or 12 months (for as little as USD15 a month, shipping included!) and, depending on the package the subscriber picks, they may receive additional perks in the form of Asymptote merchandise and ebooks (see below), but the real focus here is on creating a serious book club for a dedicated reading public. Many subscription services focus as much on the gifts as the books themselves, but we do not see ourselves as experts in tea or socks, so we’re concentrating rather on ensuring our readers get their hands on the most amazing literature we can source, applying the same curatorial instincts that won us a London Book Fair Award in 2015. READ MORE…

A quick zip through the literary world with Asymptote! Today we are visiting Iran, Brazil, and South Africa. Literary festivals, new books, and a lot more await you.

Poupeh Missaghi, Editor-at-Large, fills you up on what’s been happening in Iran:

The Persian translation of Oriana Fallaci’s Nothing and Amen finding its way into Iran’s bestsellers list almost fifty years after the first publication of the translation. The book was translated in 1971 by Lili Golestan, translator and prominent Iranian art gallery owner in Tehran, and since then has had more than a dozen editions published. The most recent round of sales is related to Golestan giving a TEDx talk in Tehran a few weeks ago about her life in which she spoke of how that book was the first she ever translated and how its publication and becoming a bestseller has changed her life.

In other exciting news from Iran, the Tehran Book Garden opened its doors to the public recently. Advertised as “the largest bookstore in the world,” the space is more of a cultural complex consisting of cinemas, cultural centers, art galleries, a children’s library, science and game halls, and more. One of the key goals of the complex is to cater to families and provide the youth with a space for literary, cultural, scientific, educational, and entertainment activities. The complex is considered a significant cultural investment for the the Iranian capital of more than twelve million residents and it has since its opening become a popular destination with people of different ages and interests.

Finally, a piece of news related to translation from Iran that is amusing but also quite disturbing. It relates to the simultaneous interpretation into Persian of President Trump’s speech in the recent U.N. General Assembly broadcasted live on Iranian state-run TV (IRIB). The interpreter mistranslated several of his sentences about Iran and during some others he remained silent and completely refrained from translating. When the act was denounced by many, the interpreter published a video (aired by the IRIB news channel and available on @shahrvand_paper’s twitter account) in which he explained that he did not want to voice the antagonistic words of Trump against his country and people. This video started another round of responses. Under the tweeted video, many users reminded him of the ethics of the profession and the role of translators/interpreters, while others used the occasion to discuss the issue of censorship and the problematic performance of IRIB in general.

Meet the Publisher: Phoneme Media’s David Shook on Translations from Underrepresented Languages

I do think we’re living in a very good time for publishing translations.

Phoneme Media is a nonprofit company that produces books in translation into English and literary films. Based in Los Angeles, the company was founded by Brian Hewes and David Shook in 2013, though it wasn’t until 2015 that the press began publishing on a seasonal calendar. To date, Phoneme Media has put out over twenty titles of fiction and poetry, and is particularly interested in publishing works from languages and places that don’t often appear in English. Many of their books are accompanied by short films that take on different formats, from video poems to book trailers, and have been shot around the world. Asymptote’s Editor-at-Large for Argentina, Sarah Moses, spoke to David Shook over Skype about publishing translations from underrepresented languages and some of the titles he’s excited about.

Sarah Moses (SM): How did Phoneme Media start?

David Shook (DS): It came about basically because of my own work as a poet and translator. In my own travels—when I was working in community-based development, mostly in East Central Africa and Latin America—through relationships, through friendships with writers, in places like Burundi and Equatorial Guinea, and writers working in indigenous languages in southern Mexico, for example, I was just encountering all of these writers that I felt deserved to be read in English, that would contribute something important to our literary dialogue and that couldn’t find homes in terms of publishers here in the United States and in the UK, too, for a couple of reasons. The first being the lack of translators working in those languages and familiar with those regions, and the second was the fact that these books were somewhat outside the purview of even the publishers who specialized in translation—some great publishers. I think of Open Letter, for example, which has largely focused on literature from European languages, which I also think is incredibly important, but something like a book of poetry from Isthmus Zapotec, or the first translation from the Lingala—a novel we’re preparing to publish later this year would definitely be a bit outside their wheel house.

SM: How do you find translators for languages like the ones you’ve mentioned?

DS: Well I think our reputation is such that, despite having been around a comparatively short time, we’re often approached by translators working in more unusual languages. Our translation from the Uyghur, for example, by Jeffrey Yang, and the author is Ahmatjan Osman, who was exiled in Canada, was exactly that situation. Jeffrey brought the translation to us because he knew of our editorial interests. In other cases, like our book of Mongolian poetry, I was alerted to its existence because the translator won a PEN/Heim grant. And I do read widely, both in search of writers and of translators, who I think are important. For example, a place like Asymptote, which I read regularly with an eye toward acquisitions. I mean when we acquired, for example, this novel from the Lingala, the translation was a huge issue because there are very few, if any, literary translators from the Lingala, so I actually auditioned a few Congolese translators before finding this husband-and-wife team, Sara and Bienvenu Sene, who did a really great job. They’re really literary translators, whereas most of the translators I’d auditioned were technical translators or interpreters. And it’s pretty spectacular, considering I think English is their fourth language. I think a big part of my work is scouting out these translators and also encouraging a new generation of translators to go out into the world and find interesting books. I’m very proud that we’ve published many first-time translators on Phoneme Media.

Weekly Dispatches from the Frontlines of World Literature

The latest from Iran, the United States, and Morocco!

Ready for your Friday World Tour? We touch down in Iran just in time for the New Year celebrations—for which thousands of books are exchanged! Then off to the States, where writers of all backgrounds are reacting to the political tumult of the times. Finally in Morocco, we’ll catch the National Conference on the Arabic Language. Let’s get going!

Poupeh Missaghi, Editor-at-Large for Iran, updates on the New Year celebrations:

The Persian year of 1395 (SH for solar Hijri calendar) will come to an end and give way to the year 1396 on Monday March 21st, the day of the spring equinox, at exactly 13:58:40 Iran’s local time. The arrival of the New Year and spring is celebrated with various Nowruz (literally meaning “new day”) traditions such as haft sin, the special table spreading that consists of seven different items all starting with the Persian letter س [sin or the “s” letter], each symbolizing one thing or another. The International Nowruz Day was inscribed on the list of UN’s Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2009.

To welcome the New Year, the Iranian literary community, like the previous year, has set up a campaign entitled Eydane ye Ketab [Nowruz gifts of book]. It began on March 5th and will run for a month, aiming to promote buying books as eydi (gifts for the Persian New Year) for friends and family instead of offering money or other gifts, or even as replacements for the calendars that companies widely give out as promotional year-end gifts. More than four thousand publishers around the country are part of this campaign and offer more than one million titles with special prices. In the first seven days of the campaign, more than 190,000 books were sold.

Some of the translation titles on the bestsellers list of the Eydane, have included: The Forty Rules of Love: A Novel of Rumi by Elif Şafak; Me Before You by Jojo Moyes; A Fraction of a Whole by Steve Totlz; After You by Jojo Moyes; Asshole No More, The Original Self-Help Guide for Recovering Assholes and Their Victims by Xavier Crement; The 52-Story Treehouse by Andy Griffiths and Terry Denton; One Plus One by Jojo Moyes; and The Little Prince by Antoine de Saint-Exupery.

Thanks to the 77 backers of our Indiegogo campaign who’ve contributed $12,736 so far, there’s already enough for us to launch a call for a Feature on Literature from Banned Countries. As new work from these affected countries will have to be specially commissioned as well as promoted, we will be directly constrained by what we manage to raise. If you’d like to see a huuge showcase to answer Trump’s new travel ban, due to be released any day now, please pitch in with a donation of whatever amount you can afford or help us spread the word about our fundraiser!

Here is the official call, taken from our submissions page:

Asymptote seeks hitherto unpublished literary fiction, literary nonfiction and poetry from the seven countries on Trump’s banned list (i.e. from authors who identify as being from Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen) that have been created in response to Trump’s travel ban, or can be interpreted as such. If selected for publication, the work will run either in our Translation Tuesday showcase at The Guardian or in our Spring 2017 quarterly edition (or both). Submissions of original English-language work will only be considered for publication in our Spring 2017 edition. For works in English translation, the decision as to where the work will be placed rests entirely at the discretion of our editor-in-chief, who curates Translation Tuesdays at The Guardian and who will be assembling this Special Feature.

While other guidelines from our submissions page apply, contributors to this Feature only will be paid at least USD200 per article.

To make sure that the articles from this Feature are circulated widely, we will leverage on our eight social media platforms in three languages, and, depending on whether our crowdfunding campaign meets its target, paid ads in high-profile media outlets to promote them for maximum impact.

Submissions can be sent directly to editors@asymptotejournal.com with the subject header: SUBMISSION: BANNEDLIT (Country/Language/Genre). Queries, which can be directed to the same email address, should carry the subject header: QUERY: BANNEDLIT

Deadline: 15 Mar 2017

Translation Tuesday: “Made in Denmark” by Mohammad Tolouei

We lived in a world in which people followed certain ideologies even for how to grip a racket.

On the subject of the travel ban, much of the rhetoric coming out of Trump’s administration has focused on the dangers posed by immigrants. This devastating but ultimately heartwarming story by Iranian writer Mohammed Tolouei, told from the point of view of a four-year-old, conveys to us what it is like from the other side, that may not be so readily apparent to those who’ve never been forced to flee their countries. To be reckoned with, above all, in any decision to migrate, is the pain of uprooting from one’s homeland.

This short story marks the first of many in an extensive showcase we hope to bring you, spotlighting new writing—and new translations—from the seven countries Trump intends to ban. If you’d like to see more of this showcase, there’s still a week left to pitch in to our fundraiser here. If you are an author who identifies as being from Iraq, Syria, Iran, Libya, Somalia, Sudan and Yemen (or someone who translates such authors)—and would like to submit work for consideration, please get in touch at editors@asymptotejournal.com.

We lived in a house of closed doors. The door to the veranda was closed. The third room’s door was closed. The bifolding doors to the hall were closed–we had placed an American sofa in front of them. The door of the big bathroom was closed. The basement’s door was closed. The door of the toilet in the yard was closed. The door opening to the ridge roof was closed. And so was the door of the large hall all over the springs and falls and winters because we never had enough oil to heat up the whole place. Only in summers the doors opened and I could play ping pong with my mother with the ping pong table in there. She put a bedstead below my feet so that I could reach up the table and then she tried not to strike hard returns. My mother was Iranian Girls’ Schools Champion and fond of penhold grip of the racket, while I favored shakehand. We lived in a world in which people followed certain ideologies even for how to grip a racket, and from the very beginning I sided with the Western party.

Our styles were totally different. My mother used to hit short, tight topspins while my hits were rather long and loose. I was more at ease with sidespins while my mother made better topspins. Yet in spite of all the trophy cups Mother had received, I won because of my playing style—the victorious western style. Mother still followed Eastern methods, yet Father wanted to take us to Denmark, a place in the West that ironically paid living subsidies, unemployment compensation and allowance for the children like most socialist countries. And in order to convince my mother to leave, each day he locked up more and more doors of our house.

Our Fundraiser Is Now Live!

Help us bring you literature from the seven countries Trump intends to ban!

Johnny Depp was reported to have spent three million dollars firing Hunter S. Thompson’s ashes out of a canon; our endeavour is modest by comparison: we are aiming to raise at least $30,000 for an urgent showcase of marginalised voices to happen both in our Spring 2017 edition and at The Guardian (here’s an example of what you can look forward to). 20% of all proceeds will be donated directly to ACLU or Refugees Welcome. The more we raise the more we can do: e.g. a printed anthology of the work, a large-scale free event featuring these authors.

But wait, there’s more: support our campaign and you’ll receive specially autographed books by Junot Díaz, Yann Martel and George Szirtes, among others! Apart from the wide selection of books below, we’ll also give away, among our wide range of Asymptote memorabilia, a newly designed AsympTOTE—featuring artwork by the guest artist of our current issue, Dianna Xu. If you’re a loyal Asymptote supporter, you’ll certainly want to add this AsympTOTE to your collection. Don’t wait—donate to our fundraiser today!

Weekly Dispatches from the Frontlines of World Literature

This week's literary updates from the Czech Republic, Iran, and England

This Friday, we present three very distinct reports from the world of literature. Slovakian Editor-at-Large Julia Sherwood looks back at what was a great year of Czech literature in translation and gives us a sneak peek at what to look forward to this year. Her Iranian colleague Poupeh Missaghi reports on language-related issues in a human rights Twitter campaign. And finally, the UK Editor-at-Large M. René Bradshaw tells us where to head for great readings in London this month and next.

Julia Sherwood, our Editor-at-Large for Slovakia, has good news from the publishing world:

Last year proved to be a big year for Czech literature in English translation, with no fewer than eighteen publications from eight different presses at the latest count. They include, to mention just a few, Worm-Eaten Time, poet Pavel Šrut’s elegy for his homeland after the Soviet-led invasion of Czechoslovakia, translated by Deborah Garfinkle, and symbolist poet Jaroslav Durych‘s (1886-1962) 1956 novella God’s Rainbow on the expulsion of the German-speaking population from Bohemia after World War II. First published in censored form in 1969, it is now available in full in David Short’s translation as part of Karolínum Press’s Modern Classics series, which also features Eva M. Kandler’s translation of the World War II literary horror The Cremator by Ladislav Fuks, a study of the totalitarian mindset that still resonates today (extract in BODY Literature), and served as the basis for one of the key films of the Czech new wave, directed by Juraj Herz.

On 30 November, a packed audience at the launch of Antonín Bajaja’s Burying the Season (also translated by David Short) at Waterstones Piccadilly in the heart of London included the playwright Tom Stoppard. Stoppard’s father came from the town of Zlín, the setting for this novel depicting the early years of communism in Czechoslovakia. Czech literature scholar Rajendra Chitnis introduces the book as part of an Istros Conversations podcast on Audioboom, while Michael Tate of Jantar Publishing discusses on Czech radio the challenges of bringing Central European literature to English readers.

World Literature Today picked Czech writer Magdaléna Platzová’s The Attempt as one of its Notable translations of 2016, characterizing it as “historical fiction at its best”. In an interview with the Czech cultural bi-weekly A2, the novel’s translator Alex Zucker points out that while more books by Czech authors are now being published than ever before, they don’t necessarily reach many more readers since—like translated literature in general—quite a few are brought out by small independent presses and are therefore not visible in major bookshops and rarely reviewed.

In 2017, we can look forward to Zucker’s translations of two the most acclaimed contemporary Czech writers: Jáchym Topol’s Angel Station is due from Dalkey Archive in May, and Petra Hůlová’s taboo-breaking Plastic Three Rooms will be brought out by Jantar Publishing. Budding UK translators keen to be part of this unprecedented boom in Czech literature in English can participate in the fourth annual international competition for young translators, who this year are asked to tackle an excerpt from Bianca Bellová’s The Lake by 31 March (see their call for submissions). Budding Czech-to-English translators can also dip into the treasure trove of tricky issues, complete with solutions generously shared by Melvyn Clarke, in his blog post Translating Hrdý Budžes.

Acclaimed writer Zuzana Brabcová, who sadly passed away in 2015, was posthumously awarded the Josef Škvorecký prize for her haunting last novel Voliéry [Aviaries]. And as the year drew to a close, scores of students and literature lovers mourned the loss of the legendary Fišer bookstore in Kaprova Street near Prague’s Old Town Square, which closed its doors after selling books since the 1930s.