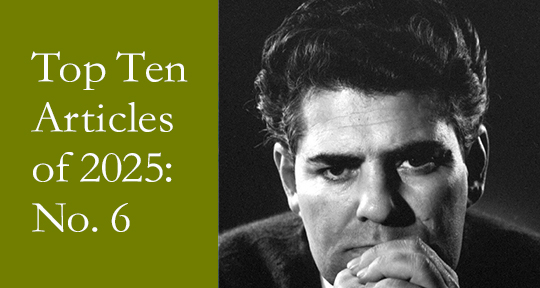

Our sixth most-read article of the year is a golden find from our Summer 2025 issue, an excerpt from the late Ahmad Shamlou’s (1925-2000) “Elegies of the Earth” (tr. Niloufar Talebi). A nominee for the Nobel Prize in Literature, Shamlou’s time-honored status as a poet, translator, editor, and Irani cultural icon is a known fact. What better time to honor the literary great than the year of his centennial? With a body of work that stretches past seventy, we have Niloufar Talebi to thank for these deftly translated verses that impart Shamlou’s belief that “poetry should incite, uplift, and endure.”

As the people’s poet from a time when poetry was public speech, Shamlou’s contemporary blend of East and West has aged all too well. His legacy lives on through poignant works; feather-light in speech yet dense in meaning.

Sample an excerpt:

from Nocturnal (Among the Eternal Suns)

Among the eternal suns

your beauty

is an anchor—

a sun

that frees me

from the dawn of all stars.Your gaze

is the fall of tyranny—

a gaze that dressed

my bare soul

in love

so fully that now

the darkest night of never

feels like nothing but a comedy of ironies.Your eyes told me

tomorrow

is a new day—

eyes that spark love!

And now, your love:

a weapon

to wrestle with my fate.*

I had thought the sun lay beyond the horizon,

that no escape remained but an early exit,

or so I had believed.Then came Aida, undoing the eternal exit.

August 1962

From Aida in the Mirror (Nil Press, 1964)

Shamlou’s romantic view of love as the ultimate weapon against oppression is a tale as old as time, one that continues to endure in its truth. Fearless and bold in its emotion, composed in mesmerizing language, this piece unlocks that which supercedes all: sacred freedom.

It’s also ultimately an eloquent reminder of what matters most from a revolutionary that came before us. With protest as poetry, resistance as love—Shamlou offers inspiring sentiments to guide us in the new year.

As we reach the second half of this year’s round-up, check-in tomorrow for number five!

READ OUR SIXTH MOST WIDELY READ ARTICLE OF THE YEAR

*****

Discover more on the Asymptote blog:

- Our Top Ten Articles of 2025, as Chosen by You: #7 Love and Mistranslation by Youn Kyung Hee

- Our Top Ten Articles of 2025, as Chosen by You: #8 The House of Termites by Ubah Cristina Ali Farah

- Our Top Ten Articles of 2025, as Chosen by You: #9 When I looked into the face of my torturer . . . I recognized my old school-friend by Bassam Yousuf