This week, our writers bring you the latest news from Central America, Sweden, and Argentina. A poetry festival featuring Latin American heavy hitters has just wrapped up in Guatemala, where, in addition, a new YA title draws from a military coup and a reprint tackles guerrilla warfare; Sweden’s most prestigious literary prize has been awarded in the fiction, non-fiction, and children’s book categories, and the Swedish Arts Council is trying to keep the literary sector afloat; a series of sundry voices gathered at a non-fiction festival in Argentina, where they spoke about how hard it is to narrate the pandemic—and how easy it is to honor another viral phenomenon. Read on to find out more!

José García Escobar, Editor-at-Large, reporting from Central America

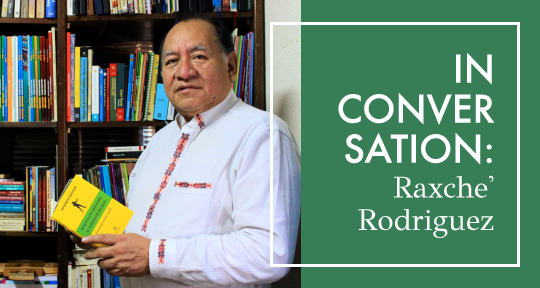

Guatemala just finished the sixteenth edition of the celebrated Festival Internacional de Poesía de Quetzaltenango (FIPQ). As a virtual festival, it included readings and presentations of notorious poets including Cesar Augusto Carvalho (Brasil), Isabel Guerrero (Chile), Yousif Alhabob (Sudan), Rosa Chavez (Guatemala), and Raúl Zurita (Chile). Relive FIPQ’s closing ceremony with a performance of the Guatemalan indie-pop band, Glass Collective, here.

Guatemalan novelist and translator David Unger just put out a new YA book. Called Sleeping with the Light On, it is based on how the author and his family experienced the 1954 US-backed military coup, which overthrew the democratically elected president Jacobo Arbenz. Sleeping with the Light On (Groundwood Books) is illustrated by Carlos Aguilera.

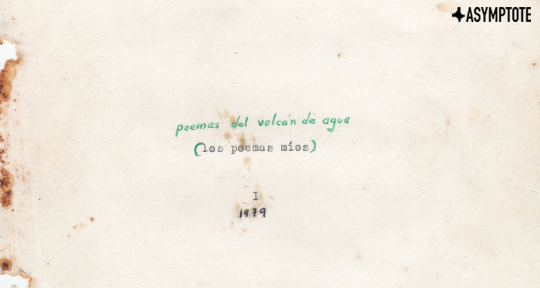

Finally, before the end of the year Catafixia Editorial will reissue two essential books of Guatemalan history and literature, Yolanda Colom’s Mujeres en la alborada and Eugenia Gallardo’s No te apresures en llegar a la Torre de Londres porque la Torre de Londres no es el Big Ben. READ MORE…