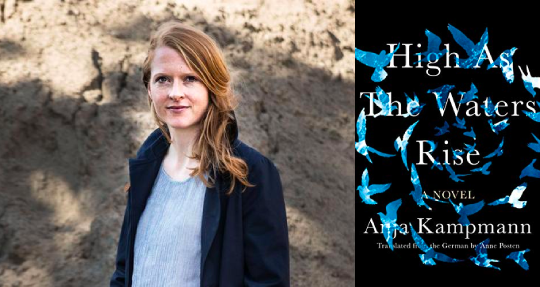

In the fall of 2018, translator Anne Posten told me about a German book she had fallen in love with, about oil rig workers, male intimacy, the nature of memory, and the cost of freedom. I begged her to send me the pages she had translated that same night and was bowled over from the very first sentence. Two years later, I had the honor of publishing at Catapult Anja Kampmann’s debut novel, High as the Waters Rise, in Anne’s translation, which promptly became a finalist for the 2020 National Book Award in Translated Literature.

High as the Waters Rise is the story of Waclaw, a man who grew up in a German mining town and has been working on oil platforms across the world for twelve years. When Waclaw loses his closest companion in an accident on the rig, he must embark on a journey of grief and reckoning.

Of course we all depend on the oil industry, even if the workers who run it are invisible to us. This novel makes that exploitation not only visible but intimate and personal. It is a politically urgent story, exploring the problems of a globalized capitalist society. But more than anything, it is the story of one man who stands at the margins of that society, asking what his life is worth.

Before we published it here, High as the Waters Rise had already been well received in Germany, where it won several awards and was nominated for the German Book Prize. But international literature in English translation, particularly by debut authors, must find passionate champions in order to succeed. We were thrilled when the novel found such a champion in author, critic, and translator Jennifer Croft, who alongside author Olga Tokarczuk was awarded the 2018 Man Booker International Prize for her translation of Flights.

Below, Jennifer discusses with Anja and Anne the translation process, its challenges and intimate nature, and what it means to translate a person into another language. I hope that their conversation might inspire you to read High as the Waters Rise, which Jennifer Croft has said contains “prose with the brightness of poetry, in a splendidly lucid translation.”

—Kendall Storey, Editor & Foreign Rights Manager, Catapult

Jennifer Croft (JC): How did you two meet and come to this project? How did you decide to work together? Anne, maybe you could also speak a bit about how you generally choose your translation projects.

Anja Kampmann (AK): Anne and I met years ago when I was a fellow at the International Writing Program in Iowa. We’ve been in touch ever since, as she developed her professional career as a translator and I wrote a book of poetry and High as the Waters Rise. But I never expected her to do the translation for High as the Waters Rise, just because I respect her so much in her own work. I couldn’t believe it when Anne told me that she had fallen in love with the novel and wanted to translate it. Her translation sample was wonderful and she caught the spirit and rhythm of the book right away.

Anne Posten (AP): In a way, High as the Waters Rise has been a long time in the making. Anja and I met in 2010. I had just moved to New York to start grad school at Queens College and still felt a bit like a country mouse in the big city. A mutual friend knew Anja wanted to come to New York after her time at the International Writers’ Program in Iowa and asked me if I wouldn’t mind hosting her. I said yes. Luckily, Anja and I became fast friends, and we still cherish memories from that time when we were both discovering the city and getting to know each other. We’ve kept in touch ever since, and over the course of these ten years, I fell in love with and started translating Anja’s poetry and visited her several times in Germany. In that time she published her first poetry collection and I my first book-length translations, and then Anja’s debut novel Wie hoch die Wasser steigen came out, to great success in Germany. I was thrilled for her, and entranced by the text. It was amazing to be so familiar with Anja’s poetry and then see, like magic, that same voice and style turned into a novel. I did a sample translation and wrote a long report on the novel, which I sent out to almost all of the editors I know, plus some I didn’t. There was a lot of initial interest and then, much to my surprise and dismay, radio silence. I was feeling pretty frustrated when I ran into Kendall unexpectedly on a trip to New York in November 2018 and heard that she’d started working for Catapult. When we met for drinks, Kendall asked if there was anything I might want to pitch her. I told her about the book and she was immediately intrigued. I sent her my sample and report, and the rest is history. I can still hardly believe it all worked out so perfectly—getting to work on a book I care so much about, written by a friend, and edited by someone I respect, like, and trust so much as Kendall.

AK: Yes, it felt like a perfect match. Also, it was great to have a friend by my side for the American translation, after almost five years I spent writing the book. READ MORE…