Cabo de Gata, by Eugen Ruge, tr. Anthea Bell, Graywolf Press

Review: Sam Carter, Assistant Managing Editor, US

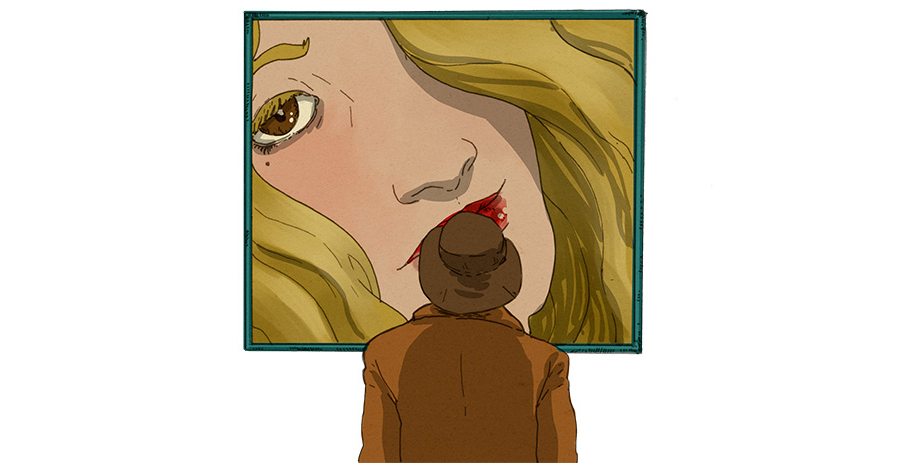

First published in German in 2013—when his In Times of Fading Light appeared in English—Eugen Ruge’s Cabo de Gata, out this month from Graywolf Press, might strike a familiar note for readers who have witnessed a surge in autobiographically-inflected works that frequently take the production of fiction as a subject worthy of novelistic exploration. Hailing from both the Anglophone world and beyond, such novels record the process of their creation or the struggles to even begin them, and Ruge quickly aligns himself with this approach in his tale of a writer’s attempt to get away from it all in the hope of figuring something out. “I made up this story so that I could tell it the way it was,” declares the dedication to this slender volume, and a more precise formulation arrives soon after as the narrator recalls a period in which “I was testing everything that I did or that happened to me at the same moment, or the next moment, or the moment after that, for its suitability as a subject … as I was living my life, I was beginning to describe it for the sake of experiment.”

While in Cabo de Gata, a small town on the Andalusian coast, the narrator quickly settles into routines designed to simultaneously distract him from blank pages and provide him with some inspiration to fill them. The local fishermen, whom the narrator visits on his daily stroll, can empathize with such difficulties: ¡Mucho trabajo, poco pescado! A lot of work for only a little fish—it’s a piscatory philosophy that applies just as well to the writing life. Ruge, however, proves to be an exceptionally gifted angler as he reels in catch after catch in what would seem to be difficult waters, namely a single man’s short trip to this seaside village.

Serving as a metronome marking out the rhythm of memories that constitute the novel, a refrain of “I remember” begins many of the paragraphs that have been expertly rendered by translator Anthea Bell. Far from repetitive or reductive, such a strategy instead seems somehow expansive, particularly when we are reminded that, “fundamentally memory reinvents all memories.” Both the vagaries and the vagueness of memories—“I remember all that only vaguely, however, like a film without a soundtrack,” remarks the narrator in a line that will be hard to forget—serve as the subjects of reflection that find their counterpart in the rhythms of the sea and the surrounding Spanish countryside.