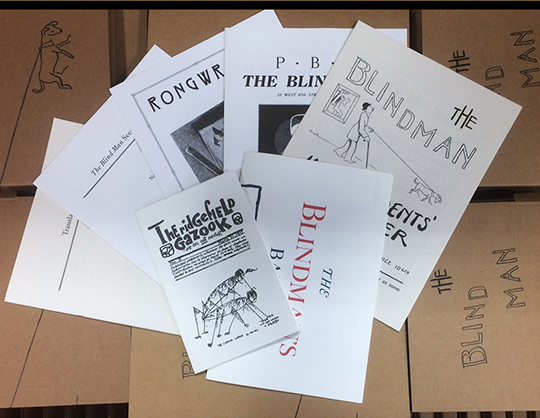

The Blind Man: 100th Anniversary Facsimile Edition edited by Marcel Duchamp, Henri-Pierre Roché, and Beatrice Wood (Ugly Duckling Press, 2017). Translated from the French by Elizabeth Zuba.

With all of the uncertainties of the current geopolitical climate, it is fitting that in the beginning of 2018 we turn our attention to the past for historical context and a better sense of the wider context of recent events. In Sophie Seita’s insightful essay that accompanies Ugly Duckling Presse’s one hundredth anniversary facsimile collection of Dadaist zines and ephemera associated with The Blind Man (referred to in Hyperallergic as “a trove of Dadaist fun”), the critic encourages readers to understand Ugly Duckling’s reissue of these magazines precisely within their broader context, with “a facsimile reprint like ours attempt[ing] to recreate the original print context and…forg[ing] new dialogues with contemporary literary and artistic communities today.” Of course, in 1917, Europe was in the throes of World War I, and the artistic movement which the The Blind Man is most closely associated, Dada, is frequently held up as “an artistic revolt and protest against traditional beliefs of a pro-war society.” Rather than simply the considerable achievement of reproducing a one hundred-year-old, self-consciously cheeky avant-garde magazine in a beautiful collector’s edition, I’m keenly interested in the dialogues Seita claims the re-edition seeks to cultivate, meditating as much on what The Blind Man tells us about the present as it tells us about the past. In my view, Ugly Duckling more than delivers.