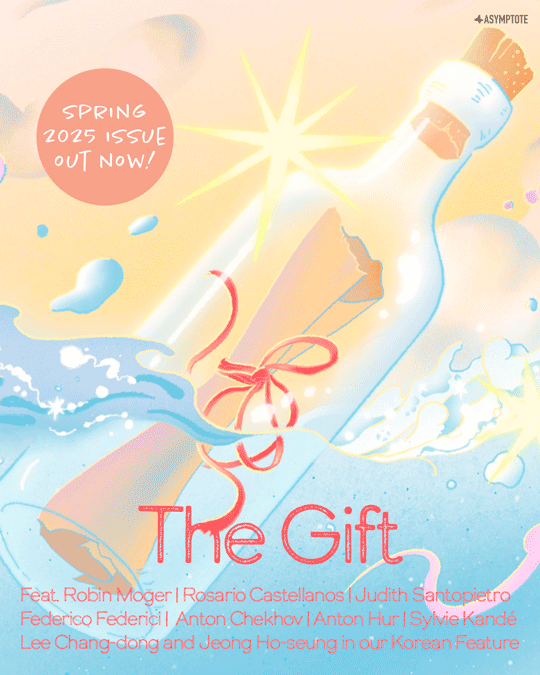

What struck me most about Anton Hur’s interview (conducted by Sarah Gear) was his clarity on AI’s role in translation. I also loved his stance on both translation and politics; every answer felt like a manifesto in miniature. Lately, I’ve been trying to delve deeper into Korean literature, and now I’m eager to read more of his work.

Jeremy Jacob Peretz and Joan Cambridge-Mayfield’s “Jombii Jamborii” was my first encounter with Guyanese Creolese in translation, and its rhythm lingers like a half-remembered song. The poem’s playfulness isn’t just aesthetic: it feels like reclamation, turning colonial language into a game where the rules keep shifting.

Youn Kyung Hee’s “Love and Mistranslation” (tr. Spencer Lee-Lenfield) unfolds like a slow revelation, each paragraph a new turn in the labyrinth of love and language. You can almost see her turning words over in her hands, testing their weight: Is this what I mean? Is this what you heard? The way she intertwines translation and love is fantastic.

Federico Federici’s asemic scripts aren’t just “unreadable” art, they are experiments in how meaning persists when grammar dissolves. When he describes languages as living organisms, I think of my own work: translation as metamorphosis, not just a bridge.

Rosario Castellanos was the first Mexican author I translated into English, so I’ll always have a soft spot for her. Translating her taught me how her quietest lines could cut the deepest. These letters (tr. Nancy Ross Jean, which I haven’t read in Spanish, by the way) feel so intimate: you sense her love for Ricardo, but also her simmering bitterness. I don’t know if this was intentional, but the timing feels poignant, as her centenary will be celebrated across Mexico later this month.

—René Esaú Sánchez, Editor-at-Large for Mexico

I grew up listening to the cadences and lingo of Guyanese Creolese and, in turn, learning to speak it myself, and I’m delighted to see Guyanese Creolese recognized as a language that merits translation in Jeremy Jacob Peretz and Joan Cambridge-Mayfield’s work. I can’t wait to read the full collection of their co-written and co-translated poems. I have had to affirm that, yes, Guyana is a country that exists, many times in my life while explaining my mixed heritage, and I’m grateful to Asymptote for bringing literary attention and awareness to this rich part of the world.

I’m only beginning to be introduced to her work, but it’s such a treat to get a glimpse into Rosario Castellanos’s private correspondence (tr. Nancy Ross Jean). Castellanos is of particular interest to me given her engagement with feminist thinkers from around the world. In the letter, Castellanos articulates a moving and beautiful relationship of love, trust, and care with Ricardo, all the while reflecting on the implications of being called his “wife” (a topic of particular interest in the feminist theory she read). Her private writing is as rich as her public work.

Youn Kyung Hee’s stunning genre-bending essay (tr. Spencer Lee-Lenfield) is one of my favourites in recent Asymptote history. It’s no accident that the tagline of this entire issue, The Gift, is taken from this work. Bookended by poetry and reflections on translation, Youn Kyung Hee manages to tackle a myriad of topics in a mutually enriching way. The idea of translation as generosity is very compelling, and I like thinking of translation as a mode of creating and sustaining a shared world through literature. This passage in particular will stick with me: “More than need, sheer innocent longing keeps me translating. Far more often, in fact. For how wonderful it would be if you, too, love the poem I love? Like sharing pastries at a nameless bakery.”