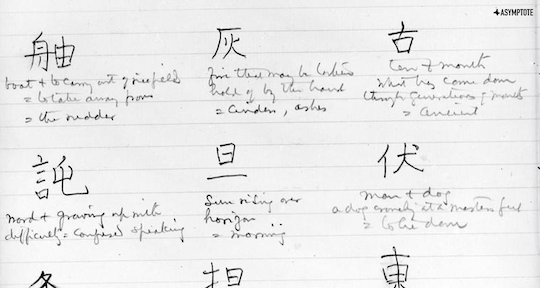

The second edition of Principle of Decision—our column that highlights the decision-making processes of translators by asking several contributors to offer their own versions of the same passage—demonstrates translation’s capacity to reveal shades of meaning in the source text. Here, Xiao Yue Shan poses to the translators a passage from Chinese writer 林棹 Lin Zhao.

轻而又轻的一天。时隔多年,那轻而又轻的一天生机犹在。如果你推却一切责任,对他人的痛苦视而不见,去拥抱巨大的明亮、明亮的寂静、寂静的自我,你就能短暂地占有那种轻而又轻。

qīng ér yòu qīng de yī tiān

轻而又轻 的一天。

A light and light day.shí gé duō nián

时隔多年

After many years,nà qīng ér yòu qīng de yī tiān

那轻而又轻的一天

that light and light dayshēng jī yóu zài

生机犹在。

still exists.rú guǒ nǐ tuī què

如果你推却

If you push asideyī qiē zé rèn

一切责任,

all responsibilities,duì tā rén de tòng kǔ

对他人的痛苦

to the pain of othersshì ér bù jiàn

视而不见,

turn a blind eye,qù yōng bào

去拥抱

go to embracejù dà de míng liàng, míng liàng de jì jìng

巨大的明亮、明亮的寂静、

the enormous and bright, bright silence,jì jìng de zì wǒ

寂静的自我,

the self of silencenǐ jiù néng duǎn zàn dì zhān yǒu

你就能短暂地占有

you can also briefly possessnà zhǒng qīng ér yòu qīng

那种轻而又轻。

that kind of light and light.

This passage is taken from the Chinese writer 林棹 Lin Zhao’s debut novel, 流溪 Liu xi, published in 2020. Its narrative takes place throughout Lingnan, a region on China’s southeast coast, weaving through dense urbanities and viridescent ruralities, the subtropical heat and myriad languages, to tell the story of a young woman whose daily life, from its very earliest days, is inextricable from violence, metamorphosis, and fantasy. A tribute to high Nabokovian style, Liu xi is a stunning, inimitable example of what is possible in the Chinese language—the music it pronounces, the visions it conjures, the delicacy and intricacy that can be excavated from its logograms.