This week it gives us great pleasure to present the winner of a student literary translation competition hosted by Monash University in collaboration with Asymptote. Conceived by Monash University lecturer, Dr. Gabriel Garcia Ochoa, the contest was held as part of his third-year undergraduate course, Translating Across Cultures. Following Susan Bassnett’s idea that translation can help us better understand the features of different cultures (read our interview with her here!), the course teaches translation as a method for developing cross-cultural competence. The students—all of whom are language majors—are divided into seven different streams: Spanish, Japanese, Mandarin, Italian, French, German, and Indonesian (with Korean forthcoming in 2019). The three students who received the highest scores on the course’s final assignment were allowed to compete in the Monash-Asymptote Literary Translation Competition.

The three finalists were asked to translate an excerpt from Katherine Brabon’s novel The Memory Artist, which won the 2016 Australian/Vogel Literary Award. Our warmest thanks to the author, the jury (made up of Monash University faculty members and Asymptote’s editorial staff), and the novel’s publisher Allen & Unwin for their kind support, in particular Emma Dorph and Maggie Thompson.

Without further ado, our heartiest congratulations to the winner Micol Licciardello, whose Italian-language translation we feature here (after the original text in English). Our applause also for the first runner-up, Beatrice Bandini, who also translated the passage into Italian, and our second runner-up, Andoni Laguna-Alberdi, who translated the passage into Spanish.

I was born in Moscow in 1964. Our apartment was a dvushka, two rooms and a small square of kitchen, in a Khrushchev-era concrete block. In that apartment of my childhood, uneven towers of paper, a precarious city, sprawled across the living room floor. On a glass-fronted bookshelf, photos of old dissidents, exiled writers and dead poets leant against the volumes and journals, looking out with silent faces. A narrow balcony faced the street.

Every child has their window, and from mine, in the kitchen, I could see only a narrow street, the tops of hats or umbrellas of people passing below, slanting shadows on the walls of the tower opposite and identical to ours, rain bouncing off bitumen, piles of snow and sometimes the old woman who cleared it away. On the windowsill were a few of those old meat tins—from the war years, my mother said—that now held pencils and fake flowers.

Life was our kitchen table. Rectangular, not very big, metal legs; draped in a cream cloth with latticed edges, stitched flowers in orange, brown and yellow. It was mesmerising, for me as a boy, to see how our rooms could transform between morning and late evening. In the morning, the table, and therefore the apartment, had a certain stillness; there were only a few ripples in the tablecloth where the base or a plate had nudged the material out of place. I could hear my mother’s slippers on the linoleum floor, the tick of the gas boiler on the wall, the soft knock of tea glasses placed on the wooden shelf. Pasha, drink your tea, my mother would say to me.

By evening our kitchen table would be another place, crowded and always, it seemed to me, made more colourful by the noise and the people gathered there. Rather than a first memory, I grasped a first feeling, an impression of those evenings in my childhood.

Oleg would usually arrive first. He had broad shoulders but was thin, the sinews of his neck stretched as if to their limits. The veins on his hands resembled river lines on a map. His hair, neatly parted, was slightly wispy, and his eyes were a striking shade of light blue. There was one night, or many, when I was very young and Oleg was talking as usual with the adults gathered in our kitchen. From my seat I watched as he casually reached for a cloth to dry the very plate from which I had moments ago eaten my dinner, that my mother had washed in the sink. In its ease, the unspoken closeness of old friends, it was a gesture that comforted me. We had probably lost my father by then. Perhaps I craved the figure of another parent that Oleg seemed to embody.

And then the others would arrive for the gathering—or underground activist meeting, as I would later learn to call these evenings in our apartment. They greeted one another, taking glasses from the table or shelf, some talking loudly as they walked through the tiny entranceway from the hall, pausing by the door to take off their boots, others quieter, patting me on the shoulder. I could smell makhorka tobacco as if it drifted in with those tall figures, riding on the warmth of their wheezing laughs or the cold of the draught from the hallway. Since the table was so small, most stood leaning against the wall, the doorway, or the edge of the sink. Certain papers were sometimes lifted from beneath the linoleum on the floor. Oleg would turn the radio on, wink at me and say, Let’s find out what’s happening to us today, Pasha. And then voices from Radio Liberty, Voice of America, or the BBC would speak from the shiny mint-green Latvian radio that was moved to the table for those gatherings—another object, like the kitchen table, that became so deeply woven into events of those years that it was something of a character in my memories. Such things seemed to hold an emotional personality as real as those of the people who, after all, would themselves become only memory objects of a kind.

***

Sono nato a Mosca nel 1964. Il nostro appartamento era una dvushka, due camere e una piccola cucina quadrata, in un palazzo di cemento dell’epoca di Kruscev. In quell’appartamento della mia infanzia, torri di carta irregolari, una città precaria, erano sparse sul pavimento del soggiorno. Su una vetrinetta, foto di vecchi dissidenti, scrittori esiliati e poeti morti erano poggiate su libri e riviste e ci guardavano con volti silenziosi. Un balcone stretto si affacciava sulla strada.

Tutti i bambini hanno una finestra e dalla mia, in cucina, vedevo soltanto una strada stretta, le cime dei cappelli e degli ombrelli della gente che passava giù, ombre oblique sui muri della torre di fronte identica alla nostra, la pioggia rimbalzare sul bitume, mucchi di neve e a volte la vecchia signora che la spalava. Sul davanzale c’erano alcune scatolette di carne—quelle degli anni della guerra, diceva mia madre—che ora contenevano matite e fiori finti.

Il tavolo da cucina era la nostra vita. Rettangolare, non molto grande, con gambe di metallo; avvolto in una tovaglia color crema con un motivo a quadretti sui bordi e fiori ricamati arancioni, marroni e gialli. Quando ero piccolo, restavo incantato vedendo come le stanze si trasformavano fra la mattina e la tarda serata. Di mattina il tavolo, e quindi l’appartamento, erano immersi in una quiete immobile; c’era soltanto qualche increspatura sulla tovaglia dove il vaso o i piatti avevano piegato leggermente il tessuto. Sentivo le ciabatte di mia madre sul pavimento di linoleum, il ticchettio della caldaia sul muro, il tocco lieve delle tazzine riposte sulla mensola di legno. Pasha, bevi il tè, mi diceva mia madre.

Di sera il tavolo diventava un altro posto, affollato e reso sempre, ai miei occhi, più ricco di colore dal rumore e dalle persone che vi si riunivano. Piuttosto che un primo ricordo, afferrai una prima sensazione, un’impressione di quelle sere della mia infanzia.

Di solito Oleg era il primo ad arrivare. Aveva le spalle larghe ma era magro, i tendini del collo tesi quasi al limite. Le vene sulle sue mani somigliavano alle linee che segnano i fiumi sulle mappe. Portava i capelli sottili con una riga ordinata e i suoi occhi erano di un’ammaliante sfumatura di azzurro. Una notte, o molte notti, quando ero appena un bambino, Oleg parlava come ogni sera con gli adulti riuniti in cucina. Dalla sedia lo guardavo allungarsi disinvolto verso un panno per asciugare il piatto che proprio qualche istante prima avevo utilizzato a cena e che mia madre aveva sciacquato nel lavandino. Con quella disinvoltura, il tacito legame dei vecchi amici, era un gesto che mi confortava. Probabilmente mio padre era già morto in quel momento. Forse desideravo ardentemente la figura di un genitore che Oleg sembrava incarnare.

Più tardi arrivavano gli altri per la riunione—o incontro degli attivisti clandestini, il vero nome di quelle serate a casa nostra che scoprii successivamente. Si salutavano mentre prendevano un bicchiere dal tavolo o dalla mensola, alcuni parlavano a voce alta attraversando l’entrata stretta, fermandosi vicino la porta per togliersi gli stivali, altri, più silenziosi, dandomi un colpetto sulle spalle. Sentivo l’odore del tabacco makhorka come se venisse trasportato dentro da quelle sagome alte, aleggiando sul calore delle loro risate affannose o sulla corrente fredda che arrivava dal corridoio. Dato che il tavolo era molto piccolo, la maggior parte di loro stava in piedi appoggiandosi al muro, sulla porta o sui bordi del lavandino. A volte prendevano dei giornali dal pavimento di linoleum. Oleg accendeva la radio, mi faceva l’occhiolino e diceva, Scopriamo cosa ci sta succedendo oggi, Pasha. E poi voci di Radio Liberty, Voice of America o della BBC parlavano dalla radio lettone di un colore menta brillante che spostavano sul tavolo per quelle riunioni—un altro oggetto, come il tavolo da cucina, che si era fittamente intrecciato con gli eventi di quegli anni tanto da diventare quasi un personaggio dei miei ricordi. Queste cose parevano avere una personalità carica di emozioni vera quanto quella delle persone che, dopotutto, sarebbero diventate soltanto oggetti nei miei ricordi.

Katherine Brabon was born in Melbourne in 1987 and grew up in Woodend, Victoria. The Memory Artist, her first novel, won the 2016 Australian/Vogel’s Literary Award.

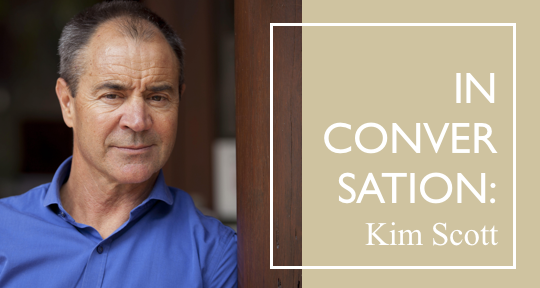

Micol Licciardello is a student at Monash University and the winner of the inaugural Monash-Asymptote Literary Translation Competition.

*****

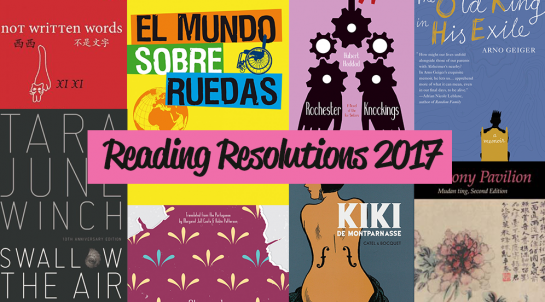

Read more translations from the Asymptote blog: