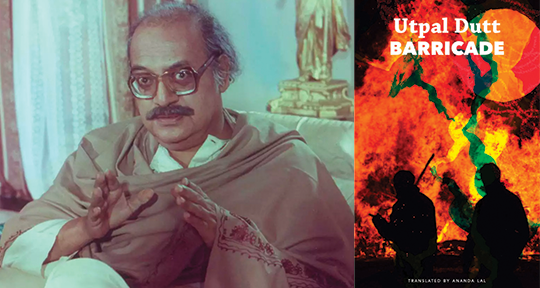

Barricade by Utpal Dutt, translated from the Bengali by Ananda Lal, Seagull Books, 2022

The Indian playwright Utpal Dutt wrote that myth is one of the most crucial forms of political storytelling because of its ability to transcend time and space, becoming relevant over and over again in new contexts. In Towards A Revolutionary Theatre, which is simultaneously a memoir of staging radical plays amidst the tense politics of his native Indian state of West Bengal in the 1960s and 1970s, and a manifesto about the necessity of leftist theatre, he cites William Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar as an example of a literary work that has “freed itself of the trappings of its own age and has become a gigantic myth,” continually reinventing itself for new political circumstances. This is seen in productions set in Benito Mussolini’s Italy, which form a critique of the tyranny, demagoguery, and mob rule that make such regimes possible.

Dutt’s play Barricade, which has been translated from the Bengali original by Indian theatre critic Ananda Lal and published by Seagull Books, is an attempt at such mythmaking. Set in the period just before the Nazi Party’s rise to power in Germany, the text is ostensibly about the party’s attempts to scapegoat their Communist rivals for the murder of an elderly political leader, but Dutt suggests throughout that the actual subject is the turbulent political situation then prevailing in West Bengal; the play was written in 1972, when the Congress-ruled government in Bengal was actively suppressing all forms of direct dissent.

However, as Lal said in a recent interview, “The fact that he set Barricade in 1933, when the Nazis rose to power in Germany, didn’t make his viewers think that it was remote from their lives. On the contrary, they connected with it viscerally, sympathised and cheered at the right moments.” This speaks to Barricade’s power as political myth, one which is increasingly relevant in the contemporary Indian context exactly fifty years after it was written, especially for its narration of how various democratic institutions such as elections, the judiciary, and the media are slowly co-opted and corrupted by the ruling party.