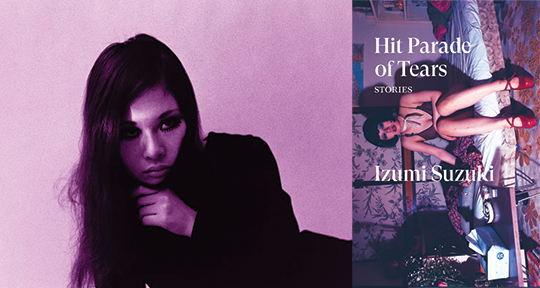

Hit Parade of Tears by Izumi Suzuki, translated from the Japanese by Sam Bett, David Boyd, Daniel Joseph, and Helen O’Horan, Verso, 2023

In the moody, deliriously humorous worlds of Hit Parade of Tears, Izumi Suzuki’s protagonists embody searing emotions, from anguish to apathy, all felt at an apex that seems like a breaking point. Sharp and achingly present, these eleven short stories are transposed by writers Sam Bett, David Boyd, Daniel Joseph, and Helen O’Horan, and present emotional and often unsettling glimpses into worlds both familiar and fantastical. Though each story stands on its own, there are elements that draw them together: the stream of Japanese rock from the 1960s and 70s playing in the background, a woman searching for her younger brother, a blurry line between mental illness and otherworldly abilities, and perhaps most consistently, a spotlight on some of the ugliest aspects of human nature—pettiness, cynicism, self-obsession, vitriol. We find these traits in her characters across the board, and those who veer from this standard are noted for their irregularity. Whether it’s a spunky teenage girl or an ungrateful husband, the dialogue in translation is natural and engaging, and each character reads with a distinct voice; descriptions are elevated by clever word choice, from a “galumphing figure” to “laparotomized remains,” and each paragraph is a newly vivid scene.

While the women of Hit Parade of Tears occupy the traditional feminine roles of wives, mothers, and sexual objects, they are not held to stereotypical ideals of femininity when it comes to their emotions and motivations, which makes this a thought-provoking and relevant read for feminists interested in non-Western perspectives. Women lead the stories in Hit Parade of Tears—with their desires, their passions, and their fears—and the men often read like props to the women’s narratives, whether that’s a self-obsessed husband, an ex-lover, a wannabe sugar daddy, a sacrifice, or a younger brother. Men’s bodies are constantly on display and under scrutiny—balding, thin, hot, or literally cut open from the stomach and hung like an ornament in a medical facility—and they rarely have any part in moving the plot forward.

The men in the protagonists’ lives belittle them and take them for granted, but the stories paint them in all their egoistic ways. In the eponymous “Hit Parade of Tears,” we spend the majority of the story listening to the thoughts of a man born over 150 years prior, who hit his prime in the 1960s and 70s. He talks down on his wife and her job archiving that era: “She’s jealous of me, he thought. She’s seething because she couldn’t take part in my youth like someone from the same generation could.” Come to find out, she’s been alive just as long as he has—they even dated briefly a hundred years ago, but he, solipsistic and self-absorbed, forgot, and he can’t imagine her experiences living up to his. Suzuki’s fiction is explicit in its critique of men’s treatment of women—hypocritical, predatory, and strikingly uncool, Suzuki’s men believe they have the upper hand in their relationships. Behind this belief, Suzuki’s women pull the strings, using the hands they’ve been dealt (as housewives, as sexy schoolgirls, as the repressed desires of a depressed woman) to their benefit. READ MORE…