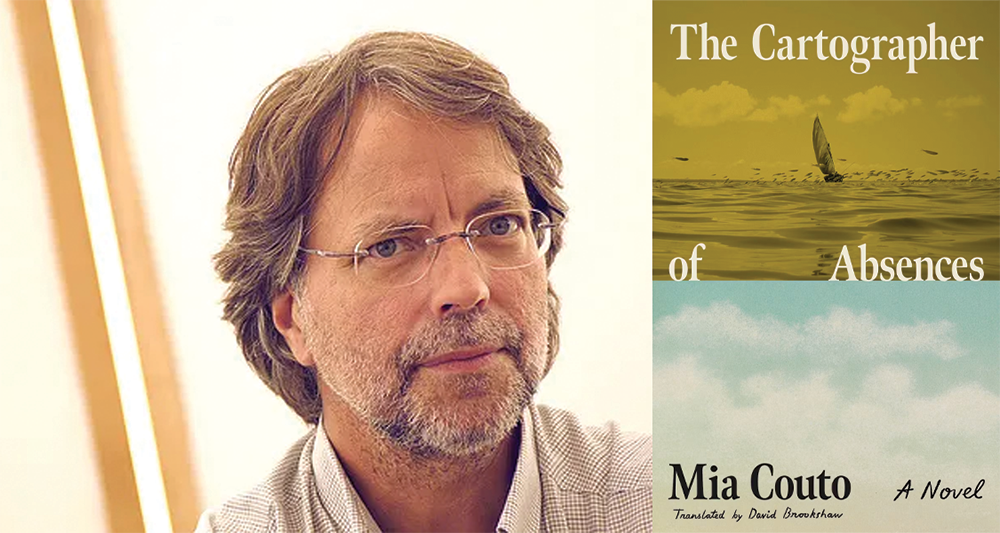

The Cartographer of Absences by Mia Couto, translated from the Portuguese by David Brookshaw, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2025

In March 2019, as Cyclone Idai bore down on Mozambique, it arrived with a weight familiar to Mia Couto. The author, born in Beira—the country’s second-largest city—in 1955, had spent decades chronicling how both natural and manmade violence has torn through his homeland, leaving open, unhealing wounds. In his latest novel, The Cartographer of Absences, the cyclone’s approach is both the temporal frame and symbolic force of such persistent fractures; the storm unearths what has been buried and almost forgotten.

The novel follows Diogo Santiago, an internationally recognized Mozambican poet, who returns to his birthplace of Beira for a literary tribute. Suffering from depression and unable to write, he sets out on the journey to ostensibly “lay his memories to rest,” and expects a ceremonial homecoming. Instead, he receives a cardboard box from Liana Campos, a mysterious resident whose grandfather once served as an inspector with PIDE—Portugal’s brutal secret police. The box contains a trove of documents from the final convulsions of Portuguese colonial rule: interrogation transcripts, confiscated poems, bureaucratic reports, and family papers. Together, they reveal the hidden architecture of violence that has shaped both Diogo and Liana’s families, including the fate of the former’s cousin, Sandro, who disappeared during the war, and the suspicious death of the latter’s mother, Almalinda. READ MORE…