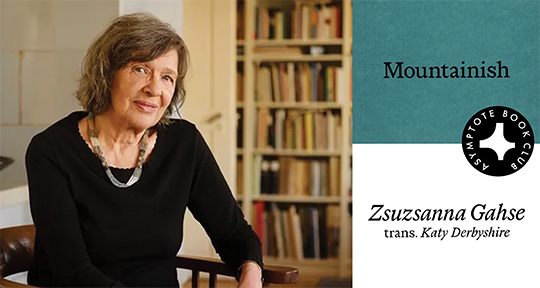

Wandering, dizzying, echoing, gorgeous—spending time with Zsuzsanna Gahse’s Mountainish is not unlike being four thousand metres above sea level; the book conjures both the vastness and the minute details of the Alps with lyrical intuition, while constantly introducing surprising insights into the peaks’ social presentation. Through both a study of mountains and a poetic testament of the mind inside all that landscape, Gahse takes us across what it means to look, listen, feel, and think—with all the awe, fear, beauty, and inequity that is inseparable from our regard of worldly wonders. We are delighted to introduce Mountainish as our Book Club selection for the month, and to be travelling together along the excursions and perceptions of this singular work’s pursuit.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

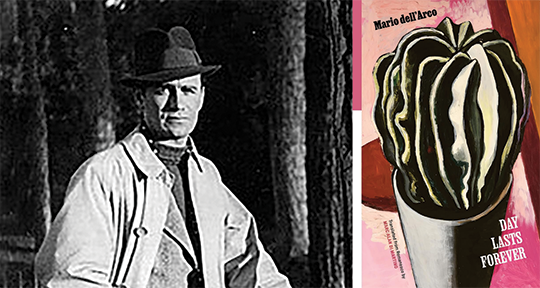

Mountainish by Zsuzsanna Gahse, translated from the German by Katy Derbyshire, Prototype, 2025

At some point while reading this strange, moreish book, one is likely to suddenly snap out of the trance it has induced, prompting a question into what this work does, and how it exerts its mesmerising effects.

Zsuzsanna Gahse’s Mountainish is a series of numbered notes, 515 in total. Certain sections appear to have come from a diary, while other parts resemble the scrambled embryo of a more substantial literary project—a travelogue, perhaps, or a parody of one. But very often, the notes never coalesce into anything; Mountainish might be best understood as the miscellaneous lint of a compulsive writer, a hodge-podge of scenes, sketches, proddings and testings of turns of phrase. This is not to say, however, that the book is lost to chaos. The numbers appended to the notes provide a semblance of order, and oblique patterns slowly emerge and disperse along the reading. Brief, slight, and faintly whimsical, the notes float by like cloud puffs, and if you look at them for long enough, they take on vaguely recognisable shapes. Within its diaphanous structure, the usual anchors to time and place—chronology, for instance—are done away with completely, leaving the book hovering ambiguously over its subject. READ MORE…