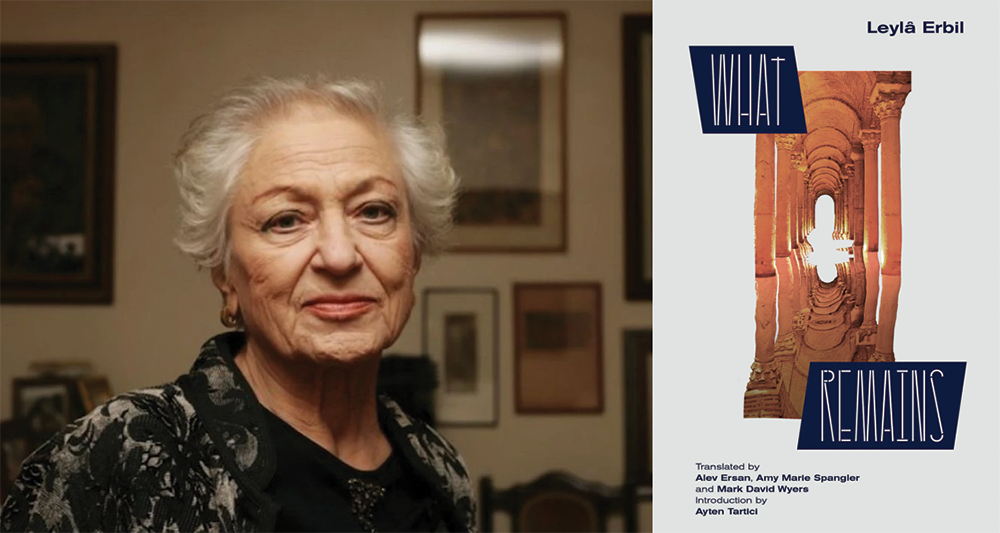

What Remains by Leylâ Erbil, translated by Alev Ersan, Mark David Wyers, and Amy Marie Spangler, Deep Vellum, 2025

In 2022, the publication of A Strange Woman (Tuhaf Bir Kadın) introduced the renowned Turkish writer and activist Leylâ Erbil to the Anglophone literary world, a step made possible by the efforts of translators Nermin Menemencioğlu and Amy Marie Spangler. What Remains (Kalan) now gives us a new side of Erbil—her first novel, characteristic with her uncompromising commitment to exploring the taboo. In a delightful moment of parallelism, Maureen Freeley’s translation of Journey to the Edge of Life by Tezer Özlü, one of Erbil’s most beloved friends and regular correspondents, came out in April, making 2025 a watershed year for Turkish women writers in translation.

Ayten Tartıcı’s insightful introduction to What Remains sets the stage beautifully, giving the reader enough context to get a sense of Erbil and her work while preserving room for mystery and surprise. Born in 1931, Erbil grew up in Istanbul and was an autodidact who did not believe in shutting herself inside the ivory tower of academia. She read widely, immersed in the work of her Turkish contemporaries but also global thinkers and writers like Kafka, Proust, Freud, Faulkner, and Marx. Undeniably a brilliant and prolific writer (as the first Turkish woman to be nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature), she was passionate, opinionated, and politically engaged in both her texts and her life, advocating for freedom of expression in Turkey and beyond. READ MORE…