Ready to dig deep? The narrator of Panni Puskás’s novel That Any Might Be Saved is, as demonstrated by this dizzying excerpt, brilliantly translated from the Hungarian by Austin Wagner. Asked by their psychotherapist to recall their childhood, the narrator draws up their very first memory: a tantrum provoked by their inability to find a plastic ball to play with. From here the narrator’s monologue unfurls in a dazzling spiral, transitioning seamlessly from their childhood recollections to their frustrating relationship with their perpetually unemployed friend and finally to the liberatory violence of vandalism and of the destruction of their mother’s possessions—an apparent rejection of their own richly remembered past, which frees them from the strictures of polite society and psychotherapy alike. Read on!

Translation Tuesday: An Excerpt from That Any Might Be Saved by Panni Puskás

I told them no mercy, you must be destroyed, because violence is the only path to happiness

An Interview with Mary Jo Bang on Translating Paradiso by Dante Alighieri

I wanted my translation to honor Dante’s decision to write the poem in the vernacular instead of in literary Latin.

In her new translation of Dante’s Paradiso, translator Mary Jo Bang has brought to bear an eagle-eyed focus on the power of lyric poetry. This book is the last of the three that form Dante’s The Divine Comedy—the most widely read of the three being Inferno, where the punishment of the sinners in Hell mirrors the nature of the sins committed in their lifetimes. The same process is at work in Purgatorio, although there, punishment is structured instead as restorative penance, which, once completed, enables the souls to enter the blissful realm of the tenth heaven. In Paradiso, then, Dante travels through the nine spheres of the solar system until he arrives at the Empyrean, where he finds the saved basking in the Eternal Light of God’s mind. Speaking to those he meets along the way, Dante becomes aware that bliss isn’t the same for everyone; one’s ability to feel God’s love in the afterlife depends on the qualities of their time spent on earth.

By translating Dante’s language into modern American English and adopting a matter-of-fact authorial tone, Bang retains the elegance of the original diction. Throughout, she adopts a loose iambic structure and preserves the three-line stanza to echo Dante’s terza rima, an arrangement he devised to gesture to the Holy Trinity. All of these measures combine to honor the imagery and meaning of Dante’s original vernacular Italian, while also acknowledging the fundamental differences between the two languages.

Curious to learn more, I spoke with Bang about the act of “carrying” poetry across from one language to another, the nuts and bolts of her translation process, and how Heaven is different for each person lucky enough to have made it there.

Tiffany Troy (TT): What is the act of literary translation for you? And has your view of the possibilities of translation shifted over time?

Mary Jo Bang (MJB): The best definition of translation I’ve encountered comes from tracing the term back to the Latin translationem (nominative translatio), which means “a carrying across.” When applied to a text, the suggestion is that you are carrying a text in one language over into a second language. The Greeks used the word for the work of metaphor, which, like the translation of a text from one language to another, is rooted in equivalency and substitution. In the Old French, translation also referred to carrying the bones of saints from one place to another, as relics. It makes sense to me that the preciousness of such bones would have gotten linguistically intertwined with the precious religious texts copied by clerical scribes. The scribes carried a text from book to book, and sometimes also from one language to another. There have been other uses of the word, from the sacred meaning of being transported (translated) to Heaven, to the secular meaning of moving plantings from one place to another.

When I began translating the Comedy, I knew little to nothing about translation. I had taken two translation workshops when I was an MFA student at Columbia in the early nineties, working on translating a French novel, but after I finished my degree and moved to St. Louis to begin teaching, the novel stayed in the cardboard box it arrived in. I don’t know that I would have ever gone back to translation except that I read Caroline Bergvall’s “Via (48 Dante Variations),” and marveled at the fact that in forty-seven translations of the first three lines of Dante’s Inferno, no two were identical. This felt like a demonstration of the fact that there is no single “right” way to translate one language into another; that might be obvious to some but for me, it was a decisive revelation and one that has been at the forefront of my mind in all of the translations I’ve worked on since. READ MORE…

Weekly Dispatches From the Frontlines of World Literature

The latest in literary news from China, Mexico, and the United States!

This week, our Editors-at-Large take us to literary fairs, readings, and walks around the world, featuring Malaysia as the country of honor at Beijing’s annual book fair, an “in-progress” translation reading in New York, and a thought-provoking reflection on a traipse around sites made famous by the works of Carlos Monsiváis in CDMX. Read on to learn more!

Hongyu Jasmine Zhu, Editor-at-Large, reporting from China

Between June 18–22, the 31st Beijing International Book Fair (BIBF) welcomed over 1,700 exhibitors from 80 countries, with Bangladesh, Belarus, Chile, Cyprus, Ethiopia, Guatemala, Jamaica, Kenya, and Oman joining for the first time. Over 300 thousand visitors of all ages and backgrounds participated in the fair’s multi-sensory literary walk, from family-friendly activities to down-to-business panel discussions.

Acts Against Fate: A Review of Cautery by Lucia Lijtmaer

Refreshingly, in Cautery, the stifling confines of gender in both past and present are treated in a way that defies easy essentialism.

Cautery by Lucía Lijtmaer, translated from the Spanish by Maureen Shaughnessy, Charco Press, 2025

Last October was a particularly busy month for news providers in Spain. Deadly, climate change-induced floods ripped through Valencia; the desperate residents of Barcelona and the Canary Islands continued to protest against unsustainable levels of tourism and unregulated property speculation; and in Madrid, sleazy stories of coercion and coverups involving a prominent young politician rattled a progressive left-wing party to its core. Despite the depressing familiarity of such headlines, it almost seems portentous that all of these subjects appear in one form or another in Lucía Lijtmaer’s 2022 novel, Cautery. An accomplished writer and co-director of the acclaimed feminist pop-culture podcast Deforme Semanal Ideal Total, which tackles everything from critical theory to modern dating, Lijtmaer’s finger is firmly on the pulse of millennial Spanish society.

Translation Tuesday: “Dear Italian School” by Marilena Delli Umuhoza

That Whiteness is taken for Italianness itself represents the very beating heart of this privilege.

For this week’s Translation Tuesday, we present to you a powerful essay by Italian-Rwandan author Marilena Delli Umuhoza, translated from the Italian by Monica Martinelli. A moment of casual racism in her daughter’s school play inspires the narrator to reflect on her own memories of bigotry as an African-origin woman growing up in 1990’s and 2000’s Italy. She traces how racial prejudice is passed down through children’s books, advertising, TV shows, and teachers; Black men and women depicted as criminals or sex objects, always, in some way, dirty. These tropes spill into modern immigration debates, where refugees are stripped of dignity, their suffering sensationalized: “And so there they were, those bodies, taking over my entire television screen without any respect for people in their most vulnerable moment: dead, naked, washed up on Italian shores.” Against this erasure, Delli Umuhoza insists on the significance of writing, of inscribing the truth of Black lives into history. Childhood racism leaves deep scars precisely because it is so pure; children, innocent yet perceptive, directly reflect the biases of society. Blending incisive cultural analysis with raw emotion, the essay makes clear why antiracist education must begin early.

A letter from an African-Italian mother

Last week I attended a musical at my daughter’s school. The show they put on was Around the World in Eighty Days, inspired by the movie recounting the adventures of Phileas Fogg.

After visiting European countries like France and Spain, welcomed by songs of joy and rather coquettish dancers, our hero comes to Africa. Welcoming him there is a person whose foolish way of speaking reminds me of the Italian dubbing actors in the film Gone with the Wind, with their mispronounced monosyllables in a typical “African” accent. I dug my nails into the fabric of my seat’s armrest, as I always do when I am nervous.

The journey continues toward the heart of Africa, where Fogg is chased by a group of Africans for unclear reasons (the acoustics were terrible and the representation pretty confusing). I thought to myself, I’m so glad they cut it. I was thinking of a scene that I had reported to the teacher six months earlier, after my daughter had come home in tears and asked me: “Mom, does grandma eat people?”

“Baby,” I replied, “what are you talking about? Of course not.”

“So why do they make us play African cannibals who eat Fogg at school?”

“What do you mean?”

“In the scene where he gets to Africa, we have to say, ‘Mmmm … It smells so tasty! What do you say, shall we cook him?’”

I was speechless. READ MORE…

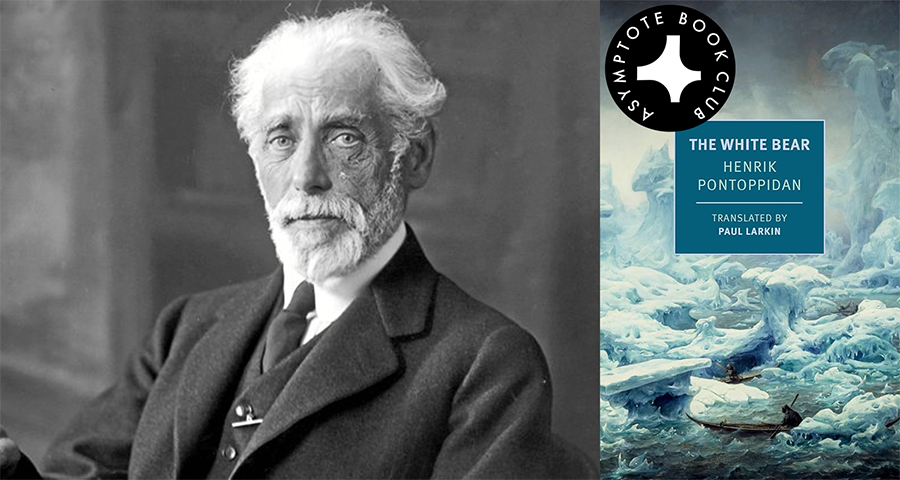

Announcing Our June Book Club Selection: The White Bear by Henrik Pontoppidan

Pontoppidan illustrates the continual tension between a contextual existence and the acknowledgment of our own freedoms. . .

Henrik Pontoppidan was one of the greatest writers and social critics of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Denmark, yet his works were only introduced to English readers over one hundred years later. Rife with cultural insight, no-holds-barred excoriations, and a firm conviction in the potential of the individual, The White Bear—a newly published collection of his two novellas—provides a valuable entrance into a writer deeply suspicious of the hypocrisies and repressions of modern life, one whom Georg Lukács praised as rendering ‘possible a journey through a really vital and dynamic life-totality by its semblance of movement’.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

The White Bear by Henrik Pontoppidan, translated from the Danish by Paul Larkin, New York Review Books, 2025

In discussing why we continue to revisit canonical tragedies despite always knowing how they will end, the classicist Bryan Doerries speaks to the worth of spectating on the human capacity for trying. Our myths are full of overwhelmingly fatalistic forces: of destiny, of divine fury, of mysterious arrivals, of certain pains. Yet they are ever-resonant to us not because of any sadistic pleasure to be derived from their characters’ sufferings, but because they have the potential to ‘wake us up to the slim possibility of human agency, of making a choice that averts imminent disaster before it’s too late’. For those in the stories, they walk certainly into their terrible ends—yet for us in the audience, we are given knowledge of the brief moments where things could have been different, where a single turn, or conversation, or even just a few extra minutes of time, could save us and the people we love. Perhaps in taking that understanding back home from the theatre into our own lives, we will have sufficient courage to live not in apathy but in boldness, knowing that there is only one thing that can possibly stand up against chance, and that is choice.

Weekly Dispatches From the Frontlines of World Literature

The latest from India, Bulgaria, and Hong Kong.

In bringing you the latest in literary news around the world, our editors speak on the mysterious disappearance of a renowned Indian literary prize, the death of an iconic Bulgarian writer and community leader, and ongoing discussions of queerness and translational crafts in Hong Kong.

Sayani Sarkar, Editor-at-Large, reporting from India

In a surprising turn of events, the JCB Prize for Literature, one of India’s leading book awards, has seemingly ended without any official announcement. The only information available is a legal notice on their website stating the “revocation of the licence” for the JCB Literature Foundation, established in 2018 by JCB India (a global manufacturer of construction equipment) with the aim of promoting and celebrating Indian writing and helping readers worldwide discover the finest contemporary Indian literature.

This development has sparked significant discussions within the literary community in India. Concerned writers and translators are left wondering whether the Prize will return in a different format, but there have been no announcements regarding the 2025 shortlist. Since 2018, a selected jury has been responsible for creating a longlist of ten, a shortlist of five, and selecting the winner. Each shortlisted author received Rs 1 lakh and their translators were awarded Rs 50,000; if a translated work is named the winner, the author received Rs 25 lakh and the translator was awarded Rs 10 lakh. This prize was previously the highest-paying literary award in India, and its sudden absence is troubling, especially given the recent surge of interest after Banu Mushtak’s Heart Lamp’s win at the International Booker Prizes this year. READ MORE…

Unhappy Ending: An Interview with Franziska Gänsler and Imogen Taylor

I wanted to connect my area with a more urgent threat of climate crisis.

A sweltering combination of domestic turmoil, existential ennui, and an increasingly threatening final disaster, Franziska Gänsler’s Eternal Summer presents the portrait of fractures both geographic and internal, translated with a natural erudition by Imogen Taylor. Set in a German spa town on the verge of being consumed by wildfire, the novel tells of a young woman who receives a pair of surprising visitors, and in this disruption of her melancholy routine, a spark of desire is awakened—something that could prove to be illuminating, or all-consuming.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

Rachel Stanyon: Franziska, you’ve had a lot of success with this debut novel in Germany; translations and film rights have been sold, and it’s received some glowing reviews in the English-language press. And Imogen, you’ve got twenty translations under your belt. How did you each get where you are now?

Franziska Gänsler (FG): I always wrote. It was my main interest even as a child, but I never felt that it could be a profession—it’s so uncertain. I’m not from an artistic family, so I didn’t know how to get there. I ended up studying to become a teacher of art and English, and had stopped writing for a few years; I was painting and doing other things creatively, then somehow I took it up again. Then writing just took over all of my time. I was lucky because I was supposed to be painting, but my professor at university allowed me to write instead. She was from the French-speaking part of Switzerland and couldn’t even read what I wrote, but she always signed off on everything. I started entering competitions, and from there my agent saw my work.

I actually wrote one book prior to this one, but nobody wanted to publish it. And then with Eternal Summer we came to Kein & Aber, which is my publishing house in German, and I’m still with them.

Imogen Taylor (IT): I think for me, it was a coincidence. I studied French and German, and then moved to Berlin after my BA in England. People started asking me to translate because they knew I could speak German and English, so I took odd jobs on for neighbours and friends. I was paid in bottles of wine for one of my first jobs. It wasn’t really very serious, and I carried on studying, with a master’s and a PhD. I was still doing some translation on the side, but not very much or seriously. And then I gradually realized that was what I really wanted to do, more than academic work. READ MORE…

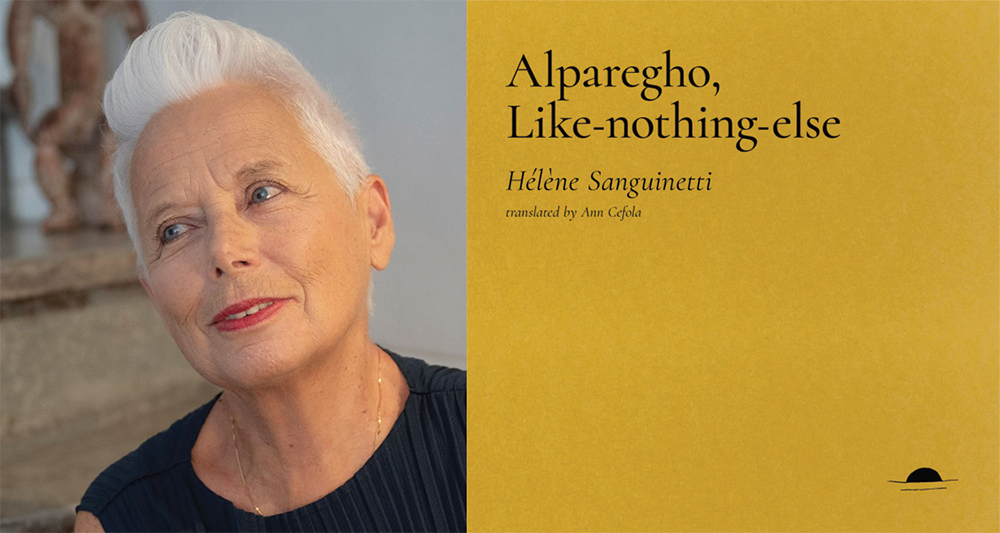

Portrait of a Faceless Man Without a Country: A Review of Alparegho, Like-nothing-else by Hélène Sanguinetti

Alparegho disarms its readers with a forceful and muscular language that tenderly rips through.

Alparegho, Like-nothing-else by Hélène Sanguinetti, translated from the French by Ann Cefola, Beautiful Days Press, 2025

Today is the day! “It’s today, / great day! / Let’s shake sheets out / the windows, / smash panes and / replace them, / empty drawers, pockets, / shelves. / Great day!” Hélène Sanguinetti’s collection, Alparegho, Like-nothing-else breaks through walls, those we erect with mortar and brick as well as the more insidious ones we draw in our minds and on the Earth. Through Ann Cefola’s translation, Alparegho effortlessly draws readers into a patchwork of vignettes that question the solidity of home and country, suggesting that these supposedly immutable objects are heavy burdens; we would be better off leaving them by the wayside. In seven chapters, the poet increasingly brings to bear the oppressive characters of the nation-state and the domestic sphere, shattering their hegemony in a sweeping motion that sweeps her readers from one scene, one place to another, looping us back and around.

Sanguinetti’s long poetic career has exhibited a practice that moves between polyphony and plasticity, and the resultant sense of vertigo disorients the internal compass as one move forward through this collection, which incorporates elements of fables, dreams, and songs to disenchant its readers from the sorcery of capitalism and authoritarianism. Alparegho opens with a potent symbol of the weight of home on our backs: a snail creeps through the dark of the night of the house, leaving a trail of slime. From there, the author slyly and gradually suggests that the rooms of the house, or the lands of the king, are interchangeable squares on a chessboard, abstract concepts just as much as lived environments. Here, home is neither comfortable nor cozy, but a rotting mess, slowly caving in. READ MORE…

Translation Tuesday: An Excerpt from Riversong by Wendy Delorme

I seek only those flammable things from which a story might be made.

Ever kept a secret way longer than you thought you would? A year? Two? What about seven? In this novel excerpt from French author Wendy Delorme, brilliantly translated by Asymptote’s own Kathryn Raver, a story of a love unspoken becomes a story about the nature of literature itself, and the parallels between writing and self-creation. Isolated in a mountain cabin, an unnamed writer reflects back on the years leading up to their relationship with their now-lover. At first hesitant to confess her feelings, she instead watches her friend’s gender transition unfold over the course of several years, only to find that as their voice and appearance change, her feelings for them deepen. When, after a an encounter on a rainy night, her feelings finally come to light, it sparks an epistolary conversation that will change both their lives. Read on!

A restless night. Sleep escapes me, but the words don’t come either. What does come is the thought of writing to you. I’m thinking again of how we met. How we really met. That night where I knew I wanted you.

Sometimes, a person comes along and we see them. Truly see them, I mean. Our perspective changes. Our line of sight suddenly sharpens, like that of an animal scrutinizing the brush to see what moves within. Our retinae focus, taking in details that up until that point had blurred together into a hazy landscape. The eye becomes curious and searches for more, latches onto a mouth, the clean line of an eyebrow, the velvety texture of a cheek, a shoulder muscle, a manner of smiling. This sort of gaze, when it lands on another, radically changes the bond two people share.

What turned my gaze on its head, that night? READ MORE…

Life Adorned with a Little Death: A Review of Journey to the Edge of Life by Tezer Özlü

This is a novel of simultaneous journeys outward and inward, through space and time, and also through memory and literature. . .

Journey to the Edge of Life by Tezer Özlü, translated from the Turkish by Maureen Freely, Transit Books, 2025

The Turkish writer Tezer Özlü lacks widespread recognition in the Anglosphere, but the tide of her English reception is turning thanks to the efforts of Maureen Freely, the translator of Nobel laureate Orhan Pamuk. In her lifetime of 1943-86, Özlü was part of a moment in modern Turkish literary history in which secular women writers proliferated. Though many of them too remain in relative obscurity among English audiences, one can only hope that the publication of Özlü’s novels will set off a domino effect.

In 2022, Deep Vellum released an updated translation (thanks to a joint but asynchronous effort between Nermin Menemencioğlu and Amy Marie Spangler) of Tuhaf Bir Kadın / A Strange Woman by Leylâ Erbil—the only Turkish women to be nominated for the Nobel as well as Özlü’s friend, source of influence, and dedicated epistolary correspondent. Originally published in 1971, Tuhaf Bir Kadın is a pioneering force in the genre of Turkish women’s writing, but proved to be a controversial text for its frank exploration of a woman’s sexuality, representation of domestic abuse, and explicit engagement with the political left. Still, it set the stage for a new generation of authors, and its legacy extends into the twenty-first century with novelists like Elif Shafak, who is committed to exposing the deep-rooted misogynistic violence of Turkish patriarchal society. For instance, her 10 Minutes 38 Seconds in This Strange World narrates the story of a murdered prostitute in Istanbul; the dead woman’s brain continues to function for the length of time in the title, a dirge for the disposability and precarity of women’s lives in the Turkish metropolis. READ MORE…

Weekly Dispatches From the Frontlines of World Literature

The latest literary news from Palestine, Kenya, and Romania!

This week, our editors-at-large take us from memorial ceremonies in Kenya to a colloquium in Brussels, exploring the life and legacy of celebrated literary figures, exciting prize nominations, and cross-cultural events. Read on to find out more!

Carol Khoury, Editor-at-Large, reporting from Palestine

Palestinian writer and poet Ibrahim Nasrallah has been nominated to the longlist for the 2026 Neustadt International Prize for Literature, better known as the “American Nobel” for its global reputation and the extent of its sway in the world of literature. Nasrallah’s much-acclaimed novel, Time of White Horses, stands as the only Arabic-language novel among this year’s nine distinguished finalists, another significant achievement for Arabic literature in the international arena.

Presented biannially by the University of Oklahoma’s World Literature Today, the Neustadt Prize recognizes outstanding literary achievement in all genres and languages. The winner, who will receive a $50,000 award, will be announced at the Neustadt Lit Fest in October 2025.

Nasrallah’s Time of White Horses is a sweeping narrative charting the course of Palestine from the twilight of Ottoman rule to the earth-shattering convulsions of the 1948 Nakba, all refracted through the lens of an imaginary village. The book, celebrated for its blend of documentary realism and imaginative storytelling, has previously been shortlisted for the International Booker Prize and is celebrated for its nuanced analysis of collective memory and identity. READ MORE…

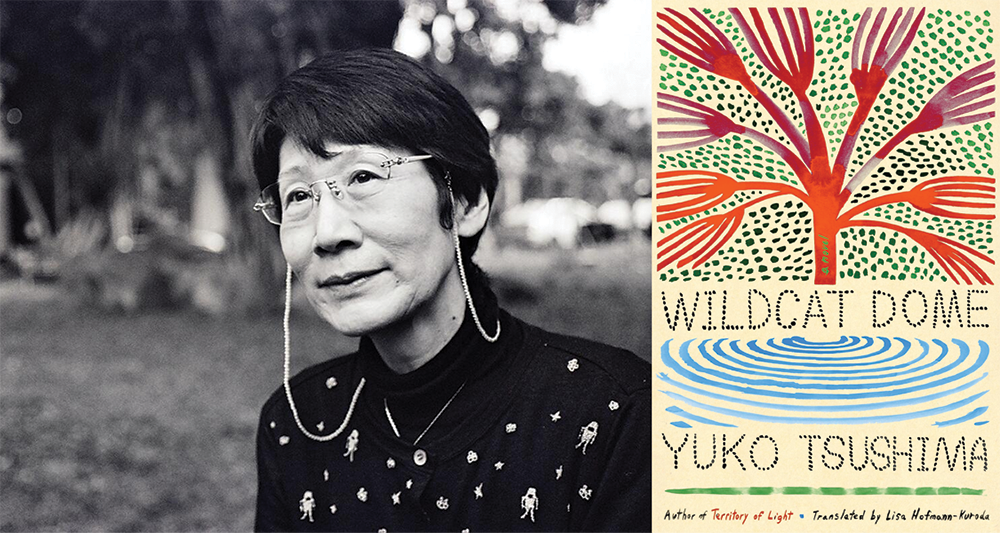

Echoes in the Dome: A Review of Yuko Tsushima’s Wildcat Dome

Radiation—its violent atomic instability—acts as a metaphor for this unresolved history.

Wildcat Dome by Yuko Tsushima, translated from the Japanese by Lisa Hofmann-Kuroda, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2025

Yuko Tsushima, perhaps one of Japan’s most quietly radical literary voices, is best known to English readers for Territory of Light and Woman Running in the Mountains—her early, semi-autofictional novels made up of domestic scenes of motherhood and explorations of non-reproductive female sexuality. In her later works, however, she turned away from the spare style that characterized her early work and towards larger-scale examinations of post-war Japan. Her newest book in translation, Wildcat Dome, in a graceful translation by Lisa Hofmann-Kuroda, introduces English-language readers to these powerful historical reckonings.

Originally published in 2013, in the wake of the tsunami that triggered the Fukushima nuclear disaster, Wildcat Dome is both a sweeping epic and a thoughtful meditation on memory, grief, and the unfinished business of history. Told through shifting narrative voices, the novel starts with a buzzing energy: a swarm of scarab beetles consuming leaves in an eerie forest, their appetite so immense that “time flows on and on, a river of emerald.” It’s a place where “insect time” collides with human time, and the buzzing doesn’t stop.

At the novel’s center are Mitch and Kazu—two children born to Japanese mothers and American GIs, then abandoned at an orphanage—and their friend Yonko, the niece of the woman who runs the orphanage. Throughout their lives, the three children, now adults, carry with them the weight of vague memories and a diffuse “prophecy.” This cryptic warning seems linked to a traumatic event that continues to haunt them into adulthood: the mysterious drowning of a fourth child, Miki-chan, a fellow orphan. As witnesses to the event, their young ages and fallible memories keep the circumstances of her death shrouded in mystery. Was it an accident, a crime, or something else? What about the strange boy, Tabo, who, unlike Mitch, Kazu, and Miki-chan, is “fully” Japanese and has a mother who will do anything to protect him—including covering his potential crimes? As the novel investigates the contradiction between the relentless passing of time and the stand-still of a history that has not been properly addressed, the prophecy shifts and mutates. Its warning comes to function as a narrative refrain rather than a concrete plot device, keeping the three main characters forever anchored to their pasts, unsettling any attempt at closure. READ MORE…